16.9: Tropical Cyclone Forecasting

- Page ID

- 10508

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)16.9.1. Prediction

The most important advance in tropical cyclone prediction is the weather satellite (see the Satellites & Radar chapter). Satellite images can be studied to find and track tropical disturbances, depressions, storms, and cyclones. By examining loops of sequential images of tropical-cyclone position, their past track and present translation speed and direction can be determined. Satellites can be used to estimate rainfall intensity and storm-top altitudes.

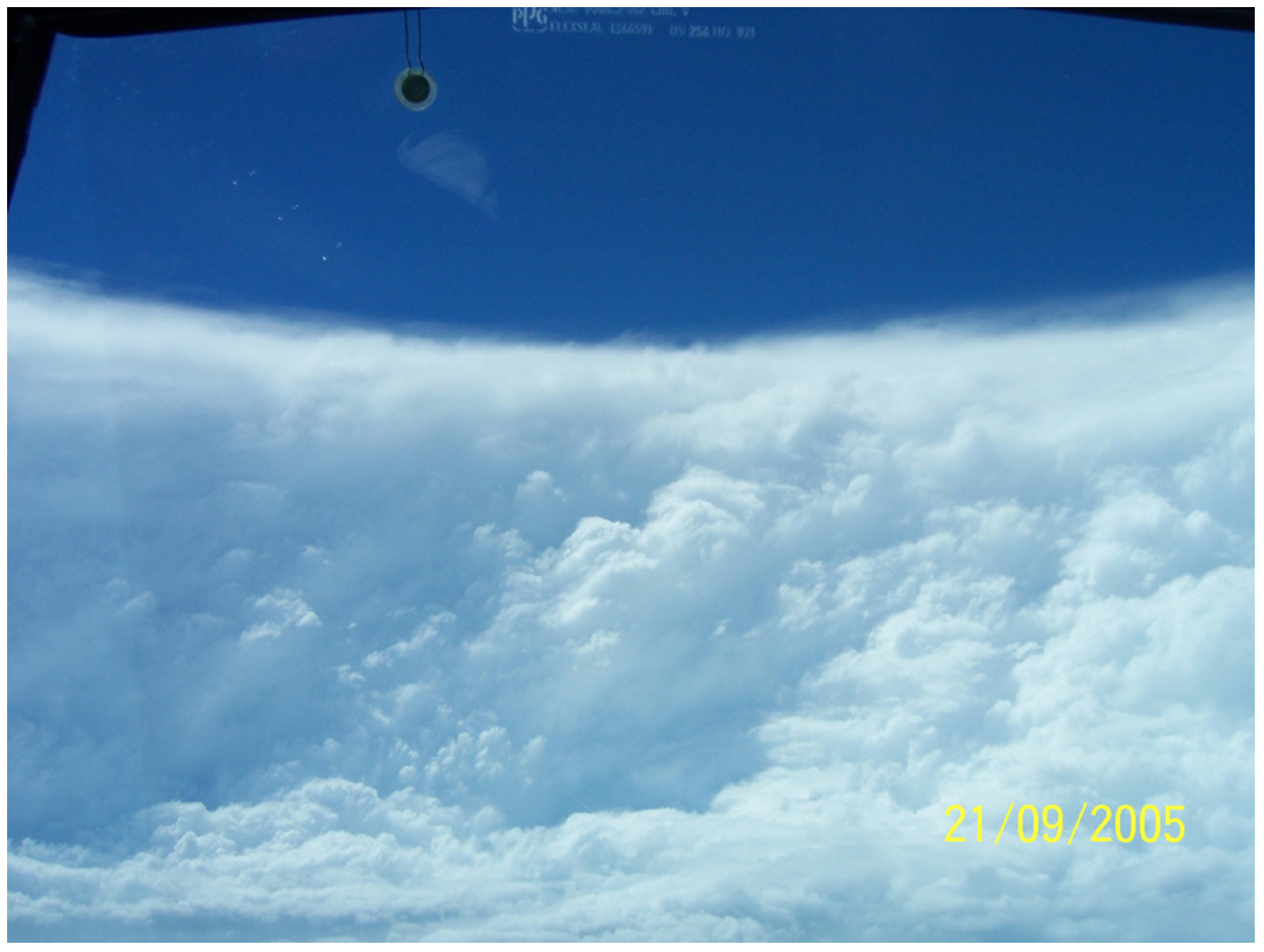

Research aircraft (hurricane hunters) are usually sent into dangerous storms to measure pressure, wind speed, temperature, and other variables that are not easily detected by satellite. Also, they can fly transects through the middle of the tropical storm to precisely locate the eye (Fig. 16.48). The two organizations that do this for Atlantic Hurricanes are the US Air Force Reserves 53rd Reconnaissance Squadron, and the Aircraft Operations Center of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

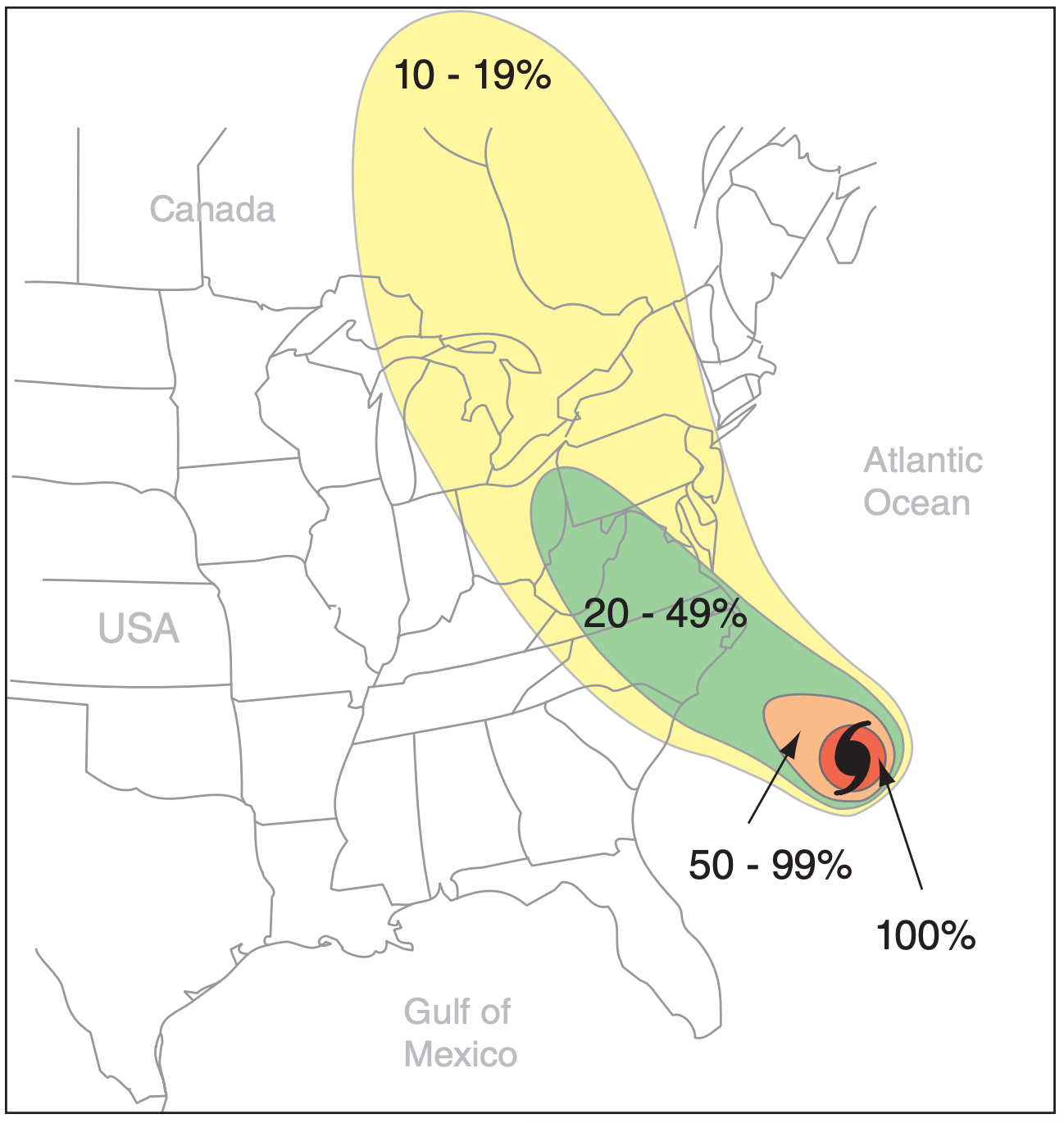

Forecasting future tracks and intensity of tropical cyclones is more difficult, and is prone to error. Computer codes (called models) describing atmospheric physics and dynamics [see the Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) chapter] are run to forecast the weather. But different models yield different forecasts of hurricane tracks. Human forecasters therefore consider all available NWP model forecasts, and issue probability forecasts (Fig. 16.49) on the likelihood that any tropical cyclone will strike different sections of coastline. Local government officials and emergency managers then make the difficult (and costly) decision on whether to evacuate any sections of coastline.

Predicting tropical cyclone intensity is even more difficult. Advances have been made based on sea-surface temperature measurements, atmospheric static stability, ambient wind shear, etc. Also, processes such as eyewall replacement and interaction with other tropical and extratropical systems are considered. But much more work needs to be done.

Different countries have their own organizations to issue forecasts. In the USA, the responsible organization is the National Hurricane Center, also known as the Tropical Prediction Center, a branch of NOAA. This center issues the following forecasts:

- Tropical Storm Watch - tropical storm conditions are possible within 36 h for specific coastal areas. (Includes tropical storms as well as the outer areas of tropical cyclones.)

- Tropical Storm Warning - tropical storm conditions are expected within 12 h or less for specific coastal areas. (Includes tropical storms as well as the outer areas of tropical cyclones.)

- Hurricane Watch - hurricane conditions are possible within 36 h for specific coastal areas.

- Hurricane Warning - hurricane conditions are expected within 24 h or less for specific coastal areas. Based on the worst of expected winds, high water, or waves.

In Canada, the responsible organization is the Canadian Hurricane Center, a branch of the Meteorological Service of Canada.

16.9.2. Safety

The US National Hurricane Center offers these recommendations for a Family Disaster Plan:

- Discuss the type of hazards that could affect your family. Know your home’s vulnerability to storm surge, flooding and wind.

- Locate a safe room or the safest areas in your home for each hurricane hazard. In certain circumstances the safest areas may not be in your home but could be elsewhere in your community.

- Determine escape routes from your home and places to meet. These should be measured in tens of miles rather than hundreds of miles.

- Have an out-of-state friend as a family contact, so all your family members have a single point of contact.

- Make a plan now for what to do with your pets if you need to evacuate.

- Post emergency telephone numbers by your phones and make sure your children know how and when to call 911.

- Check your insurance coverage — flood damage is not usually covered by homeowners insurance. • Stock non-perishable emergency supplies and a Disaster Supply Kit.

- Use a NOAA weather radio. Remember to replace its battery every 6 months, as you do with your smoke detectors.

- Take First Aid, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and disaster-preparedness classes.

If you live in a location that receives an evacuation order, it is important that you follow the instructions issued by the local authorities. Some highways are designated as evacuation routes, and traffic might be rerouted to utilize these favored routes. It is best to get an early start, because the roads are increasingly congested due to population growth. Before you evacuate, be sure to board up your home to protect it from weather and looters.

Many people who live near the coast have storm shutters permanently installed on their homes, which they can close prior to tropical cyclone arrival. For windows and storefronts too large for shutters, have large pieces of plywood on hand to screw over the windows.

If a tropical cyclone overtakes you and you cannot escape, stay indoors away from windows. Street signs, corrugated metal roofs, and other fast-moving objects torn loose by tropical cyclone-force winds can slice through your body like a guillotine.