61.3: Igneous way-up structures

- Page ID

- 22869

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Next up, we will consider the handful of igneous way-up structures. There are not as many as there are in sedimentary rocks, but though few in number, they can come in handy in deformed terranes with igneous strata or intrusions.

Vesicle concentration

In lava flows that have significant gas content, bubbles (vesicles) form as the lava degases upon eruption. These bubbles have low density, and so want to rise to the top of the fluid flow. Given a sufficiently runny lava, they can make their way upward, accumulating beneath the upper cooling crust of the flow. This creates a concentration of vesicles at the top of of flow, and more massive fine-grained textures at the base of the flow.

Caveat: Lava flows are dynamic systems, and pulsing currents of lava and differential cooling can mix up the vesicle-rich portions and vesicle-free portions. Search for other clues which corroborate the vesicles’ way-up implications.

Apophyses

Apophyses are small injection features, like small dikes, that protrude out from a lava flow or sill into surrounding pre-existing rocks. In a lava flow, they can only project downward, but in a sill they can project both upward and downward. Therefore, to use apophyses as a way-up indicator, a necessary first step is to verify that the apophyses are coming off a lava flow, not an intrusive sill. The

Post-igneous sedimentary strata laid down atop a lava flow may show their own “apophyses” as cracks in the top of the lava flow are filled in with sediment. Below is a cartoon summary of the nature of apophyses for telling sills from lava flows, and telling if lava flows are right-side-up or not:

Pillow lavas

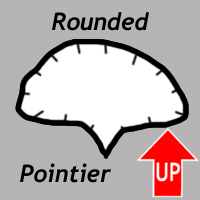

When lava erupts underwater, lava pillows form. On the outside, they have a shape like toothpaste extruded from a toothpaste tube. In cross-section, they show a glassy outer rind and fine-grained (aphanitic) interior, often with radial fractures. As a freshly formed pillow, with its still-molten interior, flows and settles into the submarine topography of older pillows, it often sags a bit in the middle, producing a little downward “pooch.” It looks something like an up-side-down teardrop shape, or a “word bubble” in a comic strip.

Bear in mind that the eruption of lava underwater is a messy process, and a variety of 3D pillow shapes can be produced. Further complications arise when we view these 3D shapes in 2D outcrops, as cross-sectional views. Many pillows are just round or cylindrical, but enough pillows show this distinctive shape that in a decent outcrop, there should be enough that you can figure out the younging direction. Sometimes, they will show more than one downward projection.

In this video, geologist Christie Rowe shows an outcrop of pillows near San Francisco, California:

Plutonic grading and cross-bedding

Crazy as it may sound, the dynamics inside a cooling pluton can mimic some of the same situations we observe at the surface with sediments deposited in flowing water. These include cross-bedding formed by magma flowing through a crystal mush, and graded bedding that results as crystals settle out from a cooling magma. The key here is that in a partially crystallized magma chamber, some minerals are more dense than the melt, and others are less dense. Ferromagnesian (mafic) minerals such as olivine and pyroxene are denser than their surroundings, and will sink if given the chance. Plagioclase feldspar is less dense, and so will “float” upward. Because the ferromagnesian minerals are dark, and the plagioclase is almost white in color, this can create visually striking patterns that are as informative as they are beautiful.

Did I Get It? - Quiz

What primary igneous structure is shown here?

a. Lava pillow

b. Vesicle grading

c. Graded layering

c. Apophysis

- Answer

-

a. Lava pillow

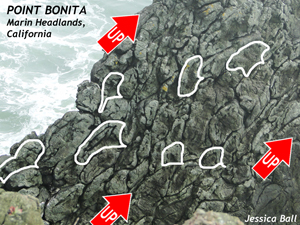

Observe this scene. What conclusions can you draw?

a. This is a site where lava once erupted underwater. Since then, these rocks have been rotated out of their original position. Paleo-"up" it to the upper left, and paleo-"down" is to the lower right.

b. This is a site where lava once erupted underwater. Since then, these rocks have been rotated out of their original position. Paleo-"up" it to the lower left, and paleo-"down" is to the upper right.

c. This is a site where magma once intruded into sediments. Since then, these rocks have been rotated out of their original position. Paleo-"up" it to the lower left, and paleo-"down" is to the lower right.

d. This is a site where magma once intruded into sediments. Since then, these rocks have been rotated out of their original position. Paleo-"up" it to the upper left, and paleo-"down" is to the lower right.

- Answer

-

a. This is a site where lava once erupted underwater. Since then, these rocks have been rotated out of their original position. Paleo-"up" it to the upper left, and paleo-"down" is to the lower right.

This lava bomb contains vesicles. Is it right-side-up or up-side-down? Explain.

a. It is right-side-up, since both the number and the size of the vesicles is larger at the top of the bomb's interior.

b. It is up-side-down, since both the number and the size of the vesicles is larger at the bottom of the bomb's interior.

- Answer

-

a. It is right-side-up, since both the number and the size of the vesicles is larger at the top of the bomb's interior.

Which way is up in this image? Several way-up indicators have been traced out to aid your interpretation.

a.

b.

c.

- Answer

-

a.