16.6: A Tropical Cyclone Model

- Page ID

- 9636

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Although tropical cyclones are quite complex and not fully understood, we can build an idealized model that mimics some of the real features.

16.6.1. Pressure Distribution

Eye pressures of 95 to 99 kPa at sea level are common in tropical cyclones, although a pressure as low as Peye = 87 kPa has been measured. One measure of tropical cyclone strength is the pressure difference ∆Pmax between the eye and the surrounding ambient environment where P∞ = 101.3 kPa:

\(\ \begin{align} \Delta P_{\max }=P_{\infty}-P_{e y e}\tag{16.10}\end{align}\)

The surface pressure distribution across a tropical cyclone can be approximated by:

\(\ \begin{align} \dfrac{\Delta P}{\Delta P_{\max }}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}\dfrac{1}{5} \cdot\left(\dfrac{R}{R_{0}}\right)^{4} & \text { for } R \leq R_{0} \\ \left[1-\dfrac{4}{5} \cdot \dfrac{R_{0}}{R}\right] & \text { for } R>R_{0}\end{array}\right.\tag{16.11}\end{align}\)

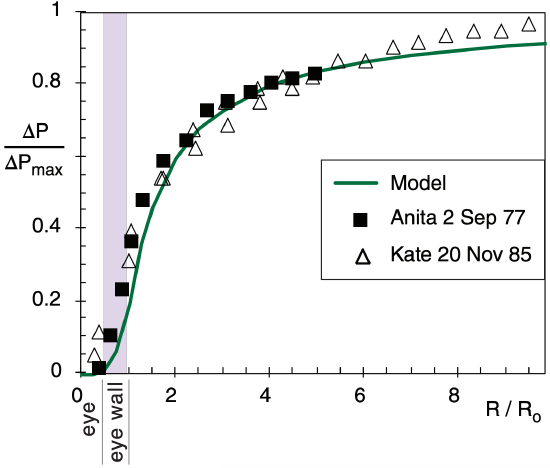

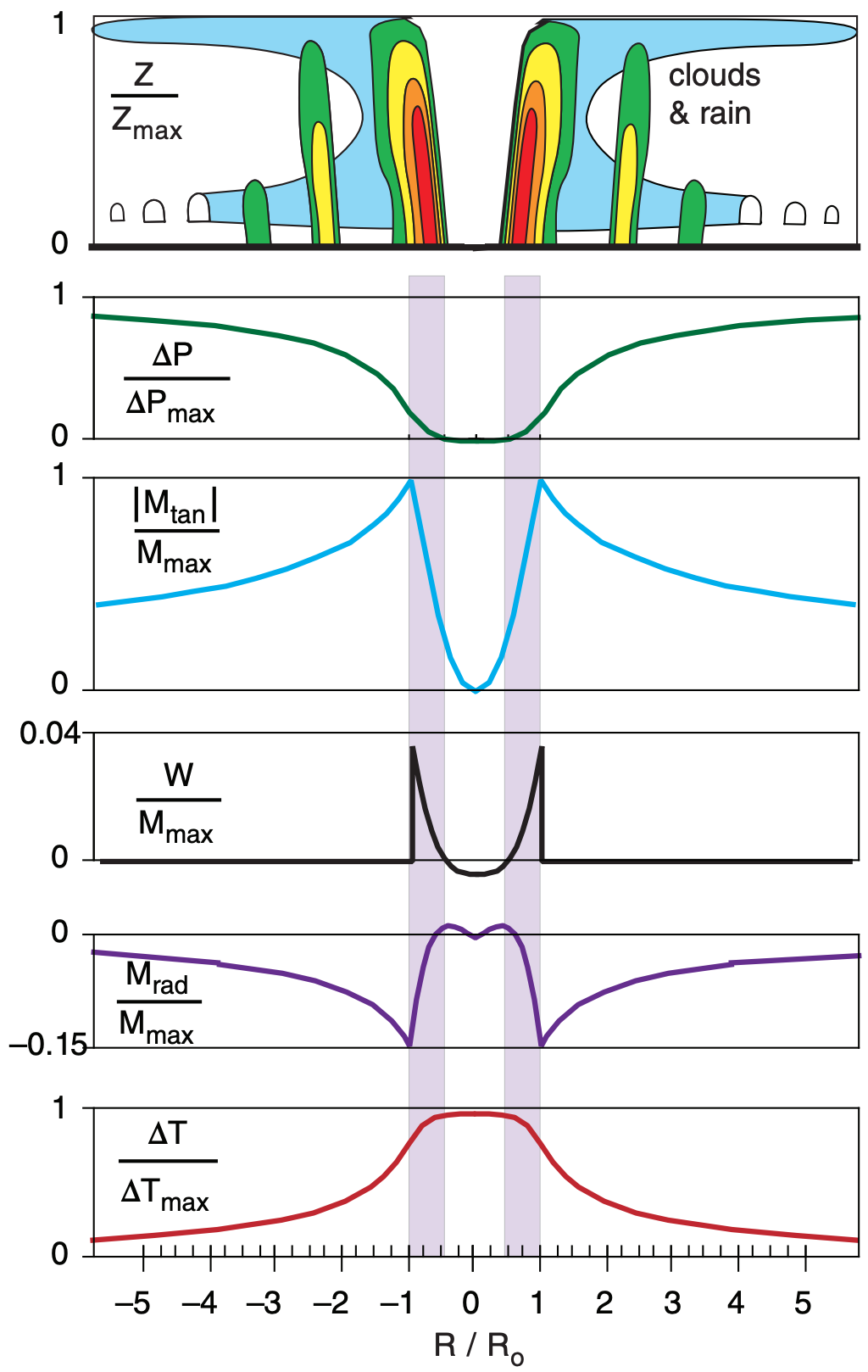

where ∆P = P(R) – Peye , and R is the radial distance from the center of the eye. This pressure distribution is plotted in Fig 16.31, with data points from two tropical cyclones.

Ro is the critical radius where the maximum tangential winds are found. In the tropical cyclone model presented here, Ro is twice the radius of the eye. Eyes range from 4 to 100 km in radius, with average values of 15 to 30 km. Thus, one anticipates average values of critical radius of 30 < Ro < 60 km, with an observed range of 8 < Ro < 200 km.

16.6.2. Tangential Velocity

To be classified as a tropical cyclone, the sustained winds (averaged over 1-minute) must be 33 m s–1 or greater near the surface. While most anemometers are unreliable at extreme wind speeds, maximum tropical cyclone winds have been reported in the 75 to 95 m s–1 range.

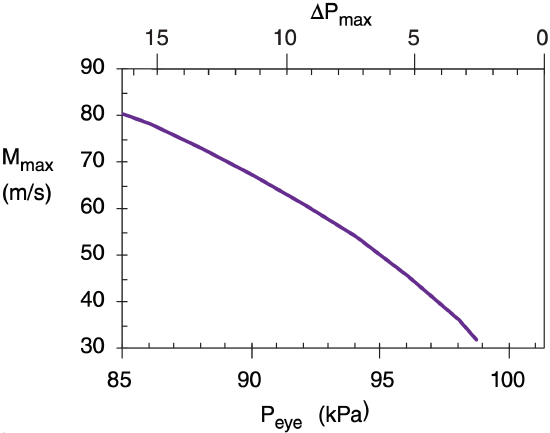

As sea-level pressure in the eye decreases, maximum tangential surface winds Mmax around the eye wall increase (Fig. 16.32). An empirical approximation for this relationship, based on Bernoulli’s equation (see the Regional Winds chapter), is :

\(\ \begin{align} M_{\max }=a \cdot\left(\Delta P_{\max }\right)^{1 / 2}\tag{16.12}\end{align}\)

where a = 20 (m s–1)·kPa–1/2 .

Sample Application

What max winds are expected if the tropical cyclone eye has surface pressure of 95 kPa?

Find the Answer

Given: PB eye = 95 kPa, Assume PB ∞ = 101.3 kPa

Find: Mmax = ? m s–1.

Assume translation speed can be neglected.

Use eq. (16.12):

Mmax = [20 (m s–1)·kPa–1/2]·(101.3–95kPa)1/2 = 50 m s–1

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: This is a category 3 tropical cyclone on the Saffir-Simpson tropical cyclone Wind Scale.

If winds are assumed to be cyclostrophic (not the best assumption, because drag against the sea surface and Coriolis force are neglected), then the previous approximation for pressure distribution (eq. 16.11) can be used to give a distribution of tangential velocity Mtan (relative to the eye) in the boundary layer:

\(\ \begin{align} \dfrac{M_{\tan }}{M_{\max }}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}\left(R / R_{0}\right)^{2} & \text { for } R \leq R_{0} \\ \left(R_{0} / R\right)^{1 / 2} & \text { for } R>R_{0}\end{array}\right.\tag{16.13}\end{align}\)

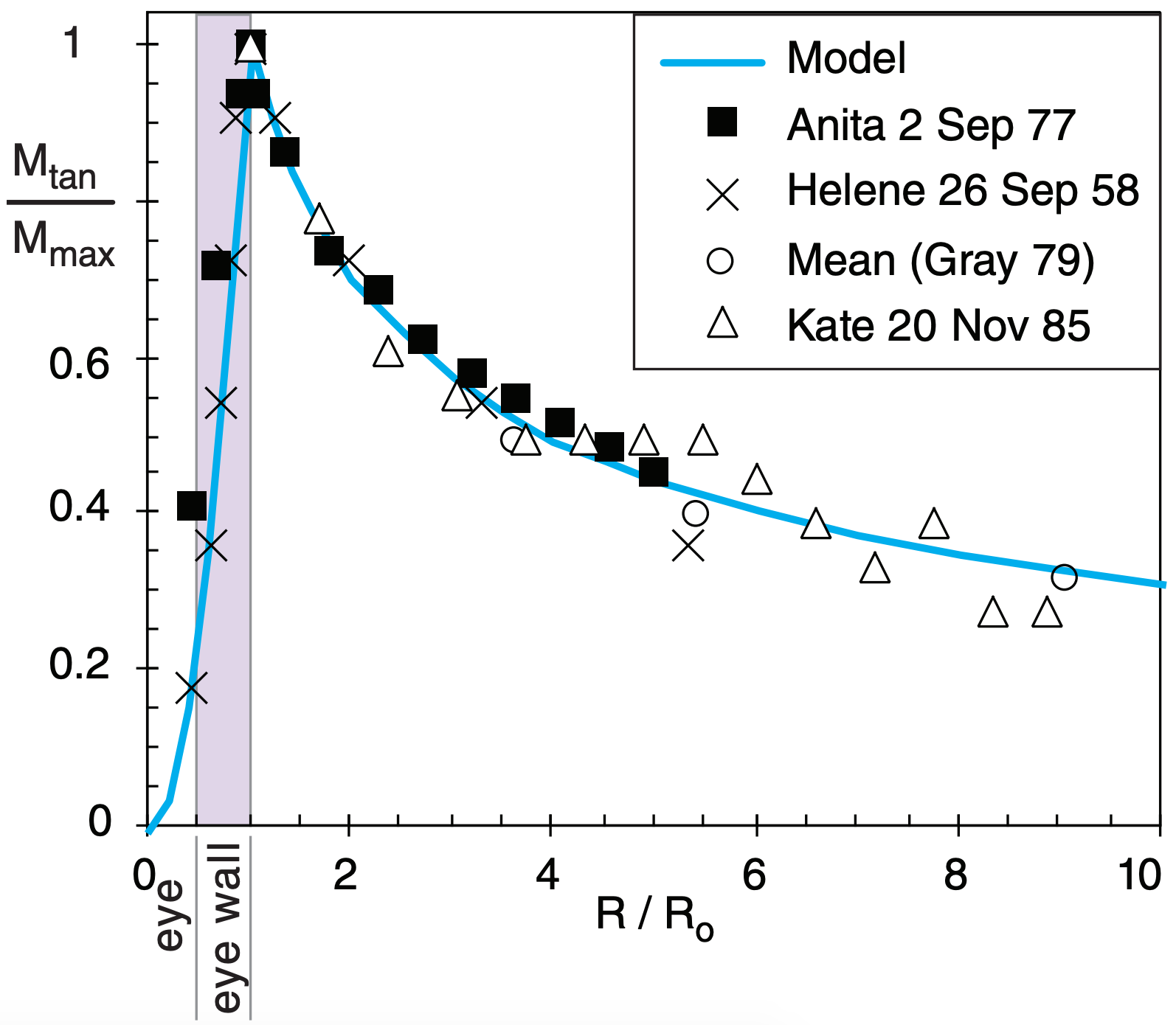

where the maximum velocity occurs at critical radius Ro (assumed to be twice the radius of the eye). This is plotted in Fig. 16.33, with data points from a few tropical cyclones.

For the tropical cyclones plotted in Fig. 16.33, the critical radius of maximum velocity was in the range of Ro = 20 to 30 km. This is a rough definition of the outside edge of the eye wall for these tropical cyclones, within which the heaviest precipitation falls. The maximum velocity for these storms was Mmax = 45 to 65 m s–1.

Winds in Fig. 16.33 are relative to those in the eye. However, the whole tropical cyclone including the eye is often moving. Tropical cyclone translation speeds (movement of the center of the storm) can be as slow as Mt = 0 to 5 m s–1 as they drift westward in the tropics, and as fast as 25 m s–1 as they later move poleward. Average translation speeds of tropical cyclones over the ocean are Mt = 10 to 15 m s–1.

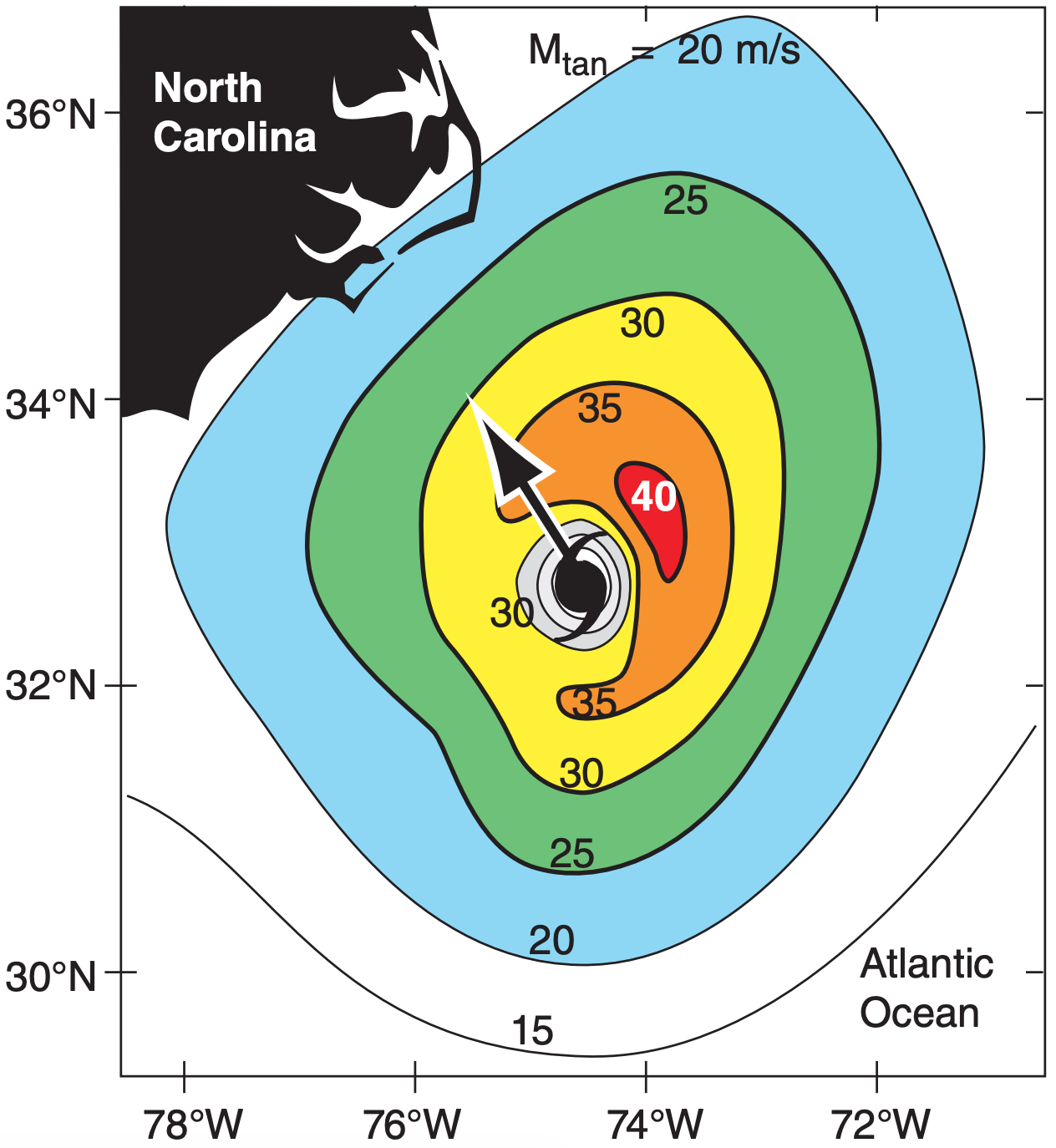

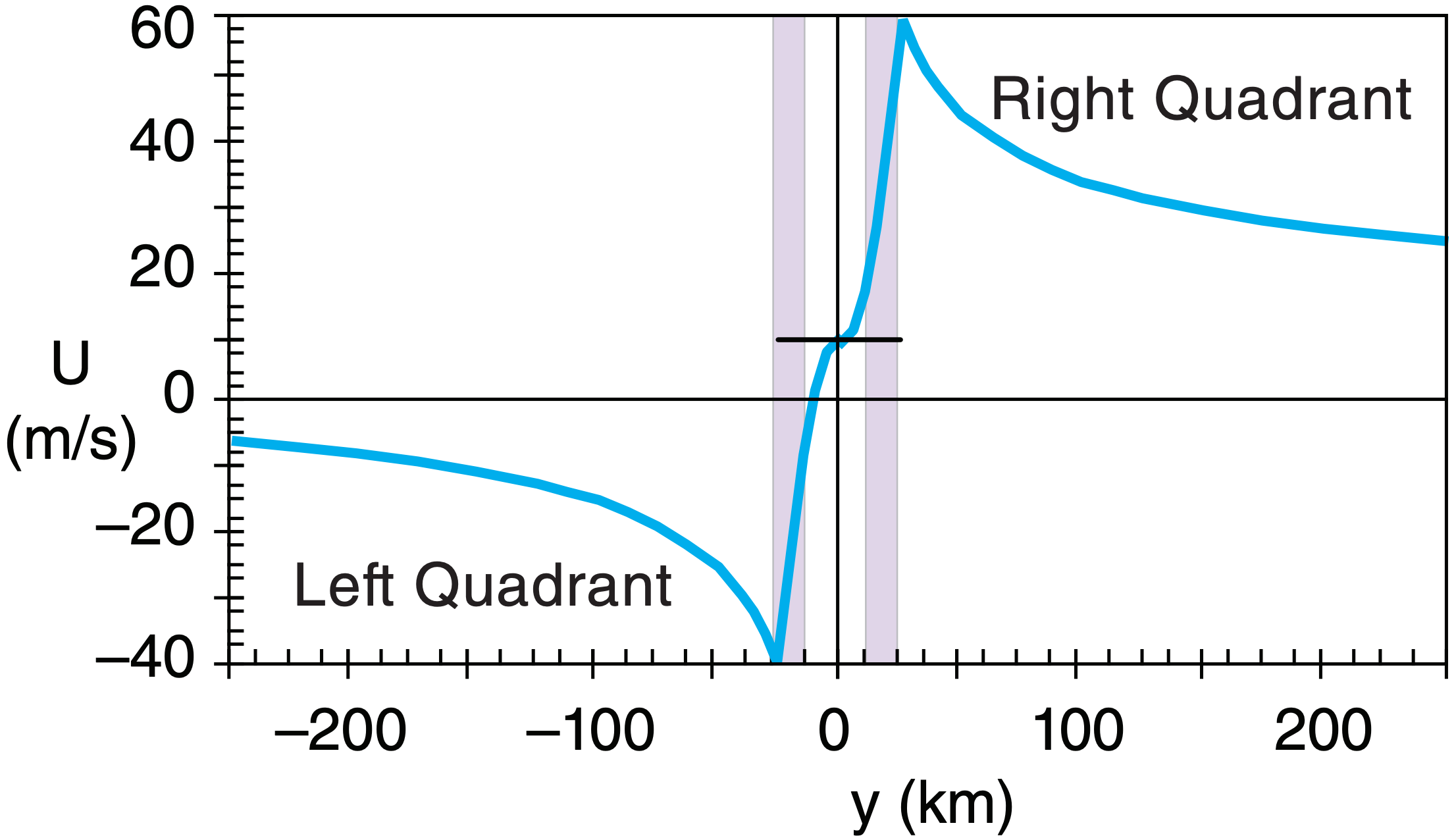

The total wind speed relative to the surface is the vector sum of the translation speed and the rotation speed. On the right quadrant of the storm relative to its direction of movement in the Northern Hemisphere, the translation speed adds to the rotation speed. Thus, tropical cyclone winds are fastest in the tropical cyclone’s right quadrant (Fig. 16.34). On the left the translation speed subtracts from the tangential speed, so the fastest total speed in the left quadrant is not as strong as in the right quadrant (Fig. 16.35).

Total speed relative to the surface determines ocean wave and surge generation. Thus, the right quadrant of the storm near the eye wall is most dangerous. Also, tornadoes are likely there.

16.6.3. Radial Velocity

For an idealized tropical cyclone, boundary-layer air is trapped below the top of the boundary layer as winds converge horizontally toward the eye wall. Horizontal continuity in cylindrical coordinates requires:

\(\ \begin{align} M_{r a d} \cdot R= constant \tag{16.14}\end{align}\)

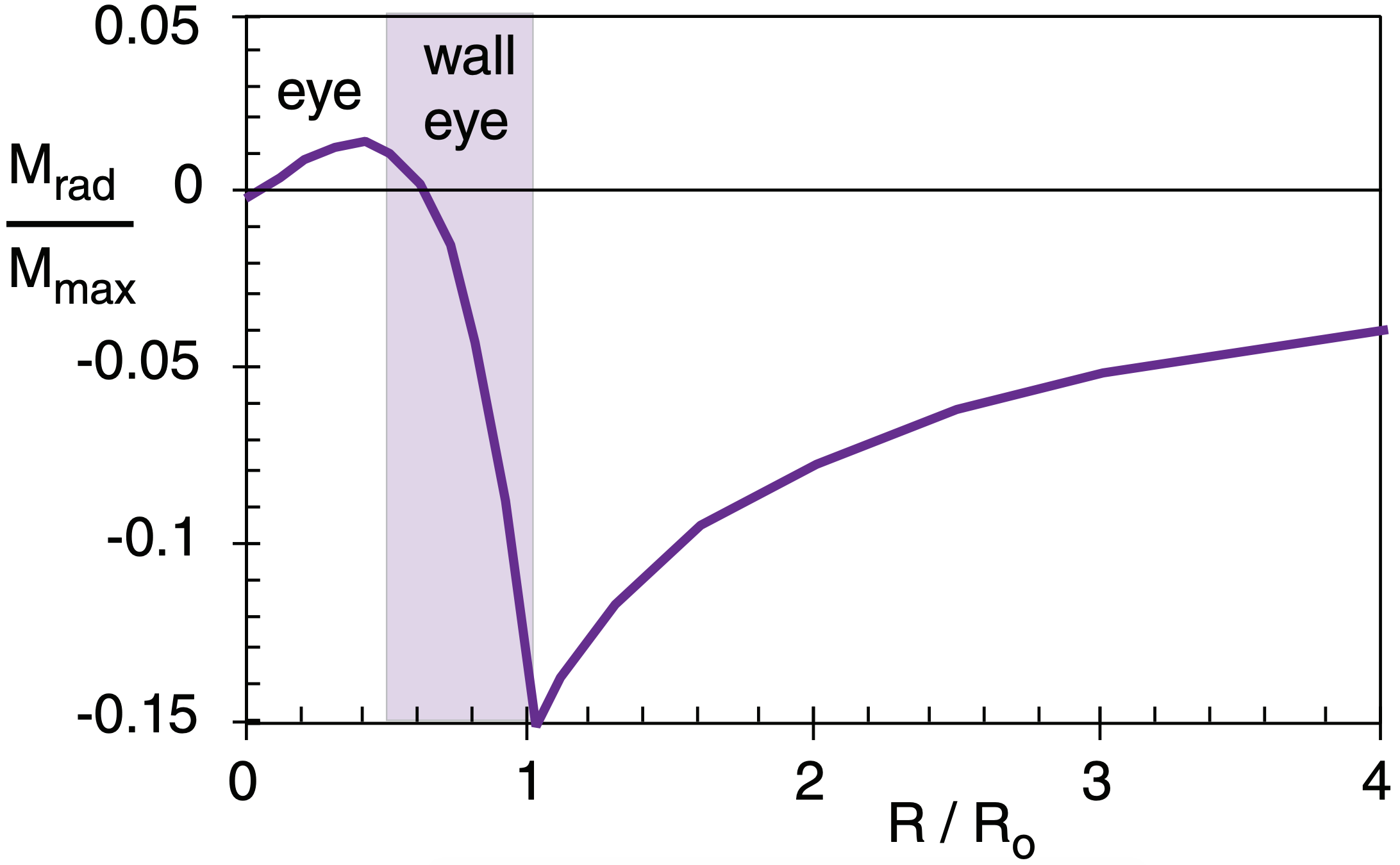

where Mrad is the radial velocity component, which is negative for inflow. Thus, starting from far outside the tropical cyclone, as R decreases toward Ro, the magnitude of inflow must increase. Inside of Ro, thunderstorm convection removes air mass vertically, implying that horizontal continuity is no longer satisfied.

As distance from the eyewall decreases, surface winds increase, which cause increasing wave height and ocean-surface roughness. The resulting turbulent drag against the ocean surface tends to couple the radial and tangential velocities, which we can approximate by Mrad ∝ Mtan2 . Drag-induced inflow such as this eventually converges and forces ascent via the boundary-layer pumping process (see the Atmospheric Forces & Winds chapter).

The following equations utilize the concepts above, and are consistent with the tangential velocity in the previous subsection:

\(\ \begin{align} \dfrac{M_{r a d}}{M_{\max }}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}-\dfrac{R}{R_{0}} \cdot\left[\dfrac{1}{5}\left(\dfrac{R}{R_{0}}\right)^{3}+\dfrac{1}{2} \dfrac{W_{s}}{M_{\max }} \dfrac{R_{0}}{z_{i}}\right] \text { for } R \leq R_{0} \\ -\dfrac{R_{0}}{R} \cdot\left[\dfrac{1}{5}+\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \dfrac{W_{s}}{M_{\max }} \cdot \dfrac{R_{o}}{z_{i}}\right] \quad \text { for } R>R_{0}\end{array}\right.\tag{16.15}\end{align}\)

where Ws is negative, and represents the average subsidence velocity in the eye. Namely, the horizontal area of the eye, times Ws, gives the total kinematic mass flow downward in the eye. The boundary-layer depth is zi , and Mmax is still the maximum tangential velocity.

For example, Fig. 16.36 shows a plot of the equations above, using zi = 1 km, Ro = 25 km, Mmax = 50 m s–1, and Ws = –0.2 m s–1. In the eye, subsidence causes air to weakly diverge (positive Mrad) toward the eye wall. Inside the eye wall, the radial velocity rapidly changes to inflow (negative Mrad), reaching an extreme value of –7.5 m s–1 for this case. Outside of the eye wall, the radial velocity smoothly decreases as required by horizontal mass continuity.

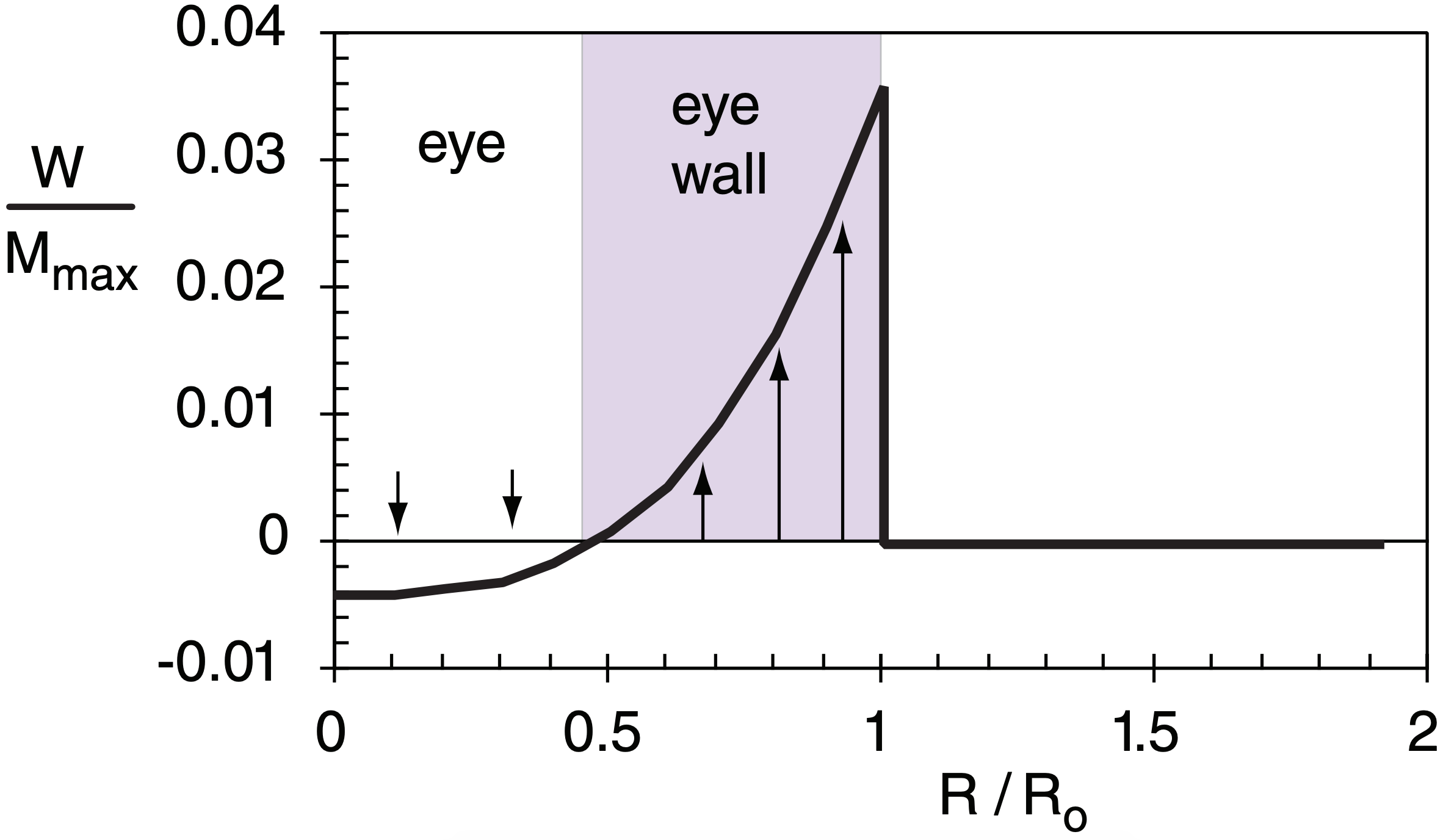

16.6.4. Vertical Velocity

At radii less than Ro, the converging air rapidly piles up, and rises out of the boundary layer as thunderstorm convection within the eye wall. The vertical velocity out of the top of the boundary layer, as found from mass continuity, is

\(\ \begin{align} \dfrac{W}{M_{\max }}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}\left[\dfrac{z_{i}}{R_{o}}\left(\dfrac{R}{R_{o}}\right)^{3}+\dfrac{W_{s}}{M_{\max }}\right] & \text { for } R<R_{o} \\ 0 & \text { for } R>R_{o}\end{array}\right.\tag{16.16}\end{align}\)

For simplicity, we are neglecting the upward motion that occurs in the spiral rain bands at R > Ro.

As before, Ws is negative for subsidence. Although subsidence acts only inside the eye for real tropical cyclones, the relationship above applies it every where inside of Ro for simplicity. Within the eye wall, the upward motion overpowers the subsidence, so our simplification is of little consequence.

Using the same values as for the previous figure, the vertical velocity is plotted in Fig. 16.37. The maximum upward velocity is 1.8 m s–1 in this case, which represents an average around the eye wall. Updrafts in individual thunderstorms can be much faster.

Subsidence in the eye is driven by the non-hydrostatic part of the pressure perturbation (Fig. 16.29). Namely, the pressure gradient (shown by the dashed green line between X’s in that Fig.) that pushes air upward is weaker than gravity pulling down. This net imbalance forces air downward in the eye.

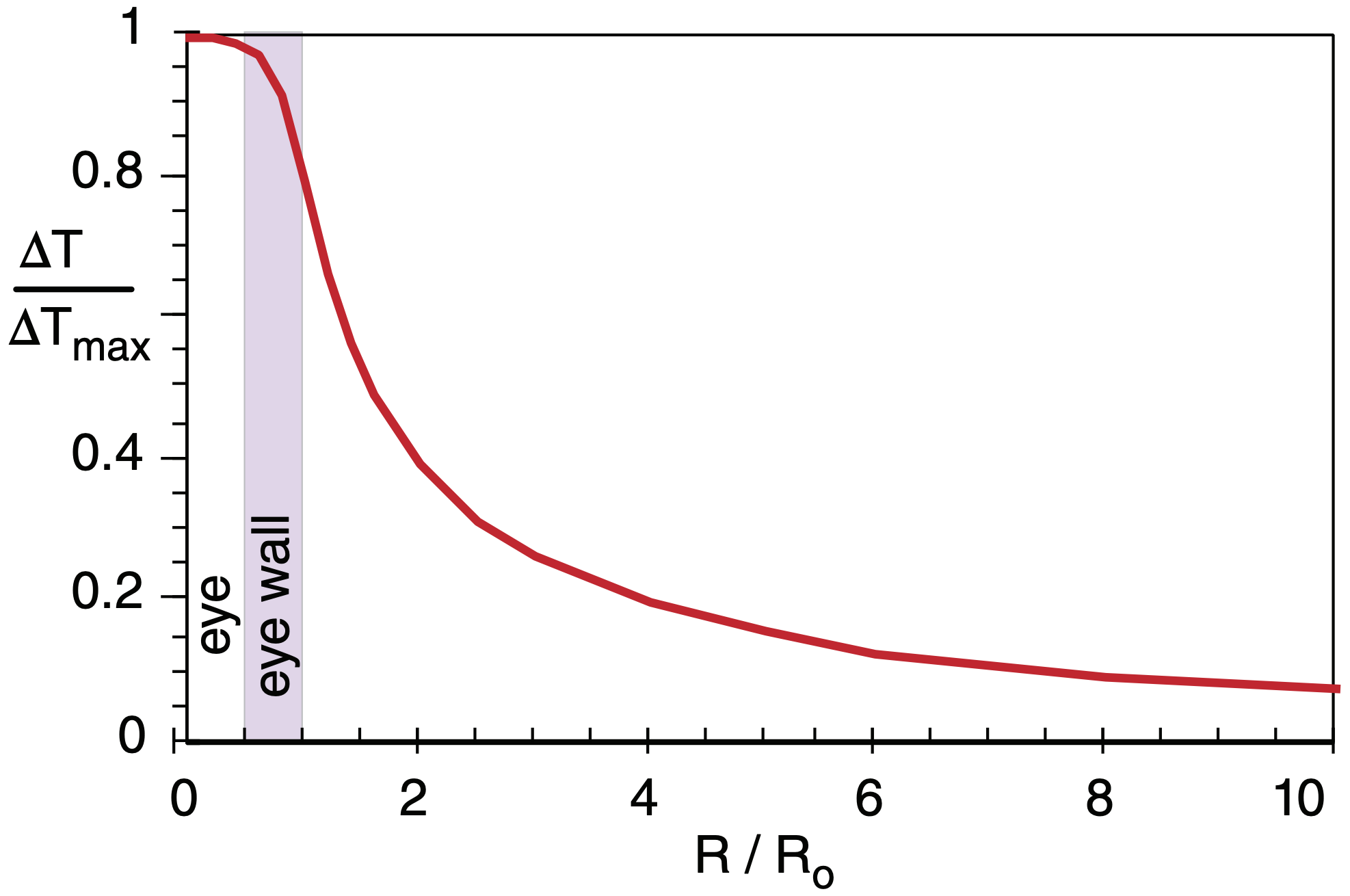

16.6.5. Temperature

Suppose that the pressure difference between the eye and surroundings at the top of the tropical cyclone is equal and opposite to that at the bottom. From eq. (16.5) the temperature T averaged over the tropical cyclone depth at any radius R is found from:

\(\ \begin{align} \Delta T(R)=c \cdot\left[\Delta P_{\max }-\Delta P(R)\right]\tag{16.17}\end{align}\)

where c = 1.64 K kPa–1, the pressure difference at the bottom is ∆P = P(R) – Peye, and the temperature difference averaged over the whole tropical cyclone depth is ∆T(R) = Teye – T(R). When used with eq. (16.11), the result is:

\(\ \begin{align} \dfrac{\Delta T}{\Delta T_{\max }}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}1-\dfrac{1}{5} \cdot\left(\dfrac{R}{R_{0}}\right)^{4} & \text { for } R \leq R_{0} \\ \dfrac{4}{5} \cdot \dfrac{R_{0}}{R} & \text { for } R>R_{0}\end{array}\right.\tag{16.18}\end{align}\)

where ∆Tmax = Teye – T∞ = c · ∆Pmax , and c = 1.64 K kPa–1. This is plotted in Fig. 16.38.

16.6.6. Composite Picture

A coherent picture of tropical cyclone structure can be presented by combining all of the idealized models described above. The result is sketched in Fig. 16.39. For real tropical cyclones, sharp cusps in the velocity distribution would not occur because of vigorous turbulent mixing in the regions of strong shear.

Sample Application

A tropical cyclone of critical radius Ro = 25 km has a central pressure of 90 kPa. Find the wind components, vertically-averaged temperature excess, and pressure at radius 40 km from the center. Assume Ws = –0.2 m s–1 in the eye, and zi = 1 km.

Find the Answer

Given: PB eye = 90 kPa, Ro = 25 km, R = 40 km, Ws = –0.2 m s–1, and zi = 1 km.

Find: P = ? kPa, T = ? °C, Mtan = ? m s–1, Mrad = ? m s–1, W = ? m s–1

Assume PB ∞ = 101.3 kPa

Figure: Similar to Fig. 16.39. Note that R > Ro.

First, find maximum values:

∆Pmax = (101.3 – 90kPa) = 11.3 kPa

Use eq. (16.12):

Mmax = [(20m s–1)·kPa–1/2]·(11.3kPa)1/2 = 67 m s–1

∆Tmax = c·∆Pmax=(1.64 K kPa–1)·(11.3kPa) = 18.5°C

Use eq. (16.11):

\(\Delta P=(11.3 \mathrm{kPa}) \cdot\left[1-\dfrac{4}{5} \cdot \dfrac{25 \mathrm{km}}{40 \mathrm{km}}\right]=5.65 \mathrm{kPa}\)

P = Peye + ∆P = 90 kPa + 5.65 kPa = 95.65 kPa.

Use eq. (16.18):

\(\Delta T=\left(18.5^{\circ} \mathrm{C}\right) \cdot \dfrac{4}{5} \cdot \dfrac{(25 \mathrm{km})}{(40 \mathrm{km})}=\underline{\mathbf{9.25^{\circ} \mathrm{C}}}\)

averaged over the whole tropical cyclone depth.

Use eq. (16.13):

\(M_{\tan }=(67 \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s}) \cdot \sqrt{\dfrac{25 \mathrm{km}}{40 \mathrm{km}}}=\underline{\mathbf{53 \mathrm{m} \mathrm{s}^{-1}}}\)

Use eq. (16.15):

\(M_{r a d}=-(67 \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s}) \cdot \dfrac{(25 \mathrm{km})}{(40 \mathrm{km})} \cdot\left[\dfrac{1}{5}+\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \dfrac{(-0.2 \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s})}{(67 \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s})} \cdot \dfrac{(25 \mathrm{km})}{(1 \mathrm{km})}\right]\)

Mrad = –6.8 m s–1

Use eq. (16.16): W = 0 m s–1

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: Using Peye in Table 16-7, the approximate Saffir-Simpson category of this tropical cyclone is borderline between levels 4 and 5, and thus is very intense.