6.1: Clastic Sedimentary Rocks

- Page ID

- 7806

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A clast is a fragment of rock or mineral, ranging in size from less than a micron[1] (too small to see) to as big as an apartment block. Various types of clasts are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and in Exercise 5.3. The smaller ones tend to be composed of a single mineral crystal, and the larger ones are typically composed of pieces of rock. As we’ve seen in Chapter 5, most sand-sized clasts are made of quartz because quartz is more resistant to weathering than any other common mineral. Many of the clasts that are smaller than sand size (less than 1/16th millimetre) are made of clay minerals. Most clasts larger than sand size (greater than 2 millimeters) are actual fragments of rock, and commonly these might be fine-grained rock like basalt or andesite, or if they are bigger, coarse-grained rock like granite or gneiss. Sedimentary rocks that are made up of “clasts” are called clastic sedimentary rocks. A comparable term is “detrital sedimentary rocks”.

Grain-Size Classification

Geologists that study sediments and sedimentary rocks use the Udden-Wentworth grain-size scale for describing the sizes of the grains in these materials (Table 6.1).

| [Skip Table] | |||

| Type | Description | Size range (millimeters) | Size range (microns) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boulder | large | 1024 and up | |

| medium | 512 to 1024 | ||

| small | 256 to 512 | ||

| Cobble | large | 128 to 256 | |

| small | 64 to 128 | ||

| Pebble (Granule) | very coarse | 32 to 64 | |

| coarse | 16 to 32 | ||

| medium | 8 to 16 | ||

| fine | 4 to 8 | ||

| very fine | 2 to 4 | ||

| Sand | very coarse | 1 to 2 | 1000 to 2000 |

| coarse | 0.5 to 1 | 500 to 1000 | |

| medium | 0.25 to 0.5 (1/4 to 1/2 mm) | 250 to 500 | |

| fine | 0.125 to 0.25 (1/8th to 1/4 mm) | 125 to 250 | |

| very fine | 0.063 to 0.125 (or 1/16th to 1/8th mm) | 63 to 125 | |

| Silt | very course | 32 to 63 | |

| course | 16 to 32 | ||

| medium | 8 to 16 | ||

| fine | 4 to 8 | ||

| very fine | 2 to 4 | ||

| Clay | clay | 0 to 2 | |

There are six main grain-size categories; five are broken down into subcategories, with clay being the exception. The diameter limits for each successive subcategory are twice as large as the one beneath it. In general, a boulder is bigger than a toaster and difficult to lift. There is no upper limit to the size of boulder.[2] A small cobble will fit in one hand, a large one in two hands. A pebble is something that you could throw quite easily. The smaller ones—known as granules—are gravel size, but still you could throw one. You can’t really throw a single grain of sand. Sand ranges from 2 millimeters down to 0.063 millimeters, and its key characteristic is that it feels “sandy” or gritty between your fingers—even the finest sand grains feel that way. Silt is essentially too small for individual grains to be visible, and while sand feels sandy to your fingers, silt feels smooth to your fingers but gritty in your mouth. Clay is so fine that it feels smooth even in your mouth.

Providing that your landscape isn’t covered in deep snow at present, visit a beach somewhere nearby—an ocean shore, a lake shore, or a river bank. Look carefully at the size and shape of the beach sediments. Are they sand, pebbles, or cobbles? If they are not too fine, you should be able to tell if they are well rounded or more angular.

The beach in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) is at Sechelt, B.C. Although there is a range of clast sizes, it’s mostly made up of well-rounded cobbles interspersed with pebbles. This beach is subject to strong wave activity, especially when winds blow across the Strait of Georgia from the south. That explains why the clasts are relatively large and are well rounded.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 6.1 answers.

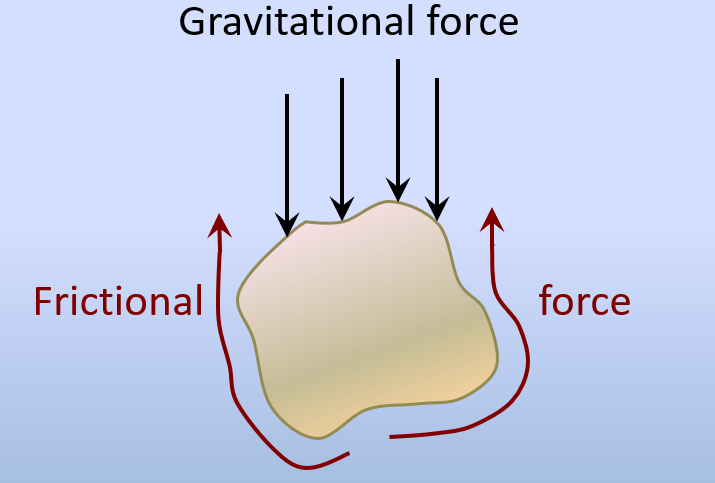

If you drop a granule into a glass of water, it will sink quickly to the bottom (less than half a second). If you drop a grain of sand into the same glass, it will sink more slowly (a second or two depending on the size). A grain of silt will take several seconds to get to the bottom, and a particle of fine clay may never get there. The rate of settling is determined by the balance between gravity and friction, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). Large particles settle quickly because the gravitational force (which is proportional to the mass, and therefore to the volume of the particle) is much greater than the frictional resistance (which is proportional to the surface area of the particle). For smaller particles the difference between gravitational push and frictional resistance is less, so they settle slowly.

Small particles that settle slowly spend longer suspended in the water, and therefore tend to get moved farther than large particles if the water is moving.

Transportation

One of the key principles of sedimentary geology is that the ability of a moving medium (air or water) to move sedimentary particles—and keep them moving—is dependent on the velocity of flow. The faster the medium flows, the larger the particles it can move. This is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Parts of the river are moving faster than other parts, especially where the slope is greatest and the channel is narrow. Not only does the velocity of a river change from place to place, but it changes from season to season. During peak discharge[3] at the location of Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), the water is high enough to flow over the embankment on the right, and it flows fast enough to move the boulders that cannot be moved during low flows.

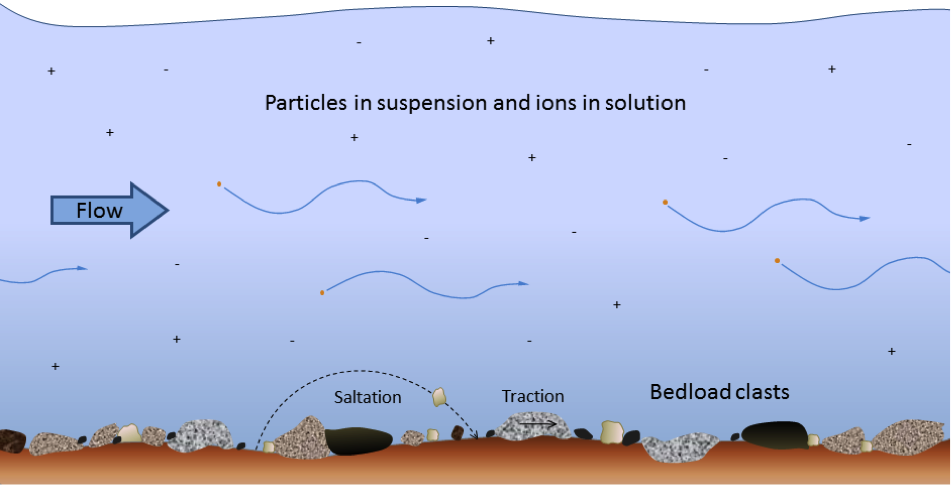

Clasts within streams are moved in several different ways, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). Large bed load clasts are pushed (by traction) or bounced along the bottom (by saltation), while smaller clasts are suspended in the water and kept there by the turbulence of the flow. As the flow velocity changes, different-sized clasts may be either incorporated into the flow or deposited on the bottom. At various places along a river, there are always some clasts being deposited, some staying where they are, and some being eroded and transported. This changes over time as the discharge of the river changes in response to changing weather conditions.

Other sediment transportation media, such as waves, ocean currents, and wind, operate under similar principles, with flow velocity as the key underlying factor that controls transportation and deposition.

Clastic sediments are deposited in a wide range of environments, including glaciers, slope failures, rivers—both fast and slow—lakes, deltas, and ocean environments—both shallow and deep. If the sedimentary deposits last long enough to get covered with other sediments they may eventually form into rocks ranging from fine mudstone to coarse breccia and conglomerate.

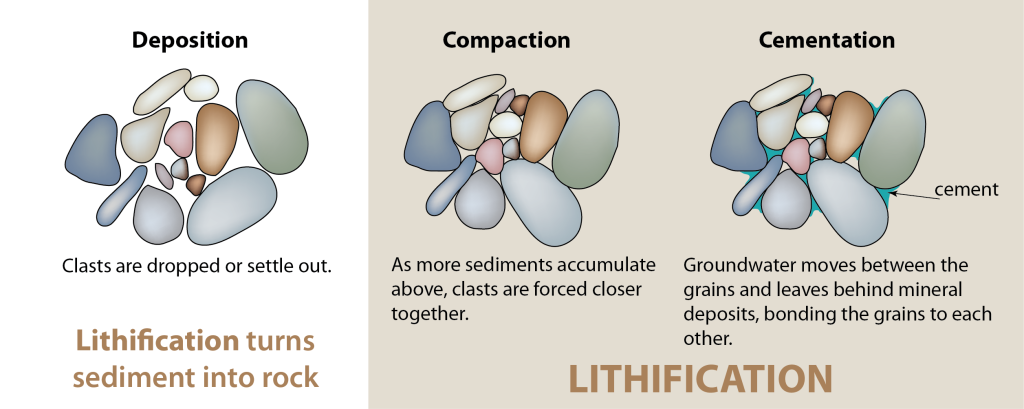

Lithification is the term used to describe a number of different processes that take place within a deposit of sediment to turn it into solid rock (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). One of these processes is burial by other sediments, which leads to compaction of the material and removal of some of the intervening water and air. After this stage, the individual clasts are touching one another. Cementation is the process of crystallization of minerals within the pores between the small clasts, and especially at the points of contact between clasts. Depending on the pressure, temperature, and chemical conditions, these crystals might include a range of minerals, the common ones being calcite, hematite, quartz and clay minerals.

The characteristics and distinguishing features of clastic sedimentary rocks are summarized in Table 6.2. Mudrock is composed of at least 75% silt- and clay-sized fragments. If it is dominated by clay, it is called claystone. If it shows evidence of bedding or fine laminations, it is shale; otherwise, it is mudstone. Mudrocks form in very low energy environments, such as lakes, river backwaters, and the deep ocean.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Group | Examples | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Mudrock | mudstone | Greater than 75% silt and clay, not bedded |

| shale | Greater than 75% silt and clay, thinly bedded | |

| Coal | Dominated by fragments of partially decayed plant matter often enclosed between beds of sandstone or mudrock. | |

| Sandstone | quartz sandstone | Dominated by sand, greater than 90% quartz |

| arkose | Dominated by sand, greater than 10% feldspar | |

| lithic wacke | dominated by sand, greater than 10% rock fragments, greater than 15% silt and clay | |

| Conglomerate | Dominated by rounded clasts, granule size and larger | |

| Breccia | Dominated by angular clasts, granule size and larger | |

Most coal forms in fluvial or delta environments where vegetation growth is vigorous and where decaying plant matter accumulates in long-lasting swamps with low oxygen levels. To avoid oxidation and breakdown, the organic matter must remain submerged for centuries or millennia, until it is covered with another layer of either muddy or sandy sediments. It is important to note that in some textbooks coal is described as an “organic sedimentary rock.” In this book, coal is included with the clastic rocks for two reasons: first, because it is made up of fragments of organic matter; and second, because coal seams (sedimentary layers) are almost always interbedded with layers of clastic rocks, such as mudrock or sandstone. In other words, coal accumulates in environments where other clastic rocks accumulate.

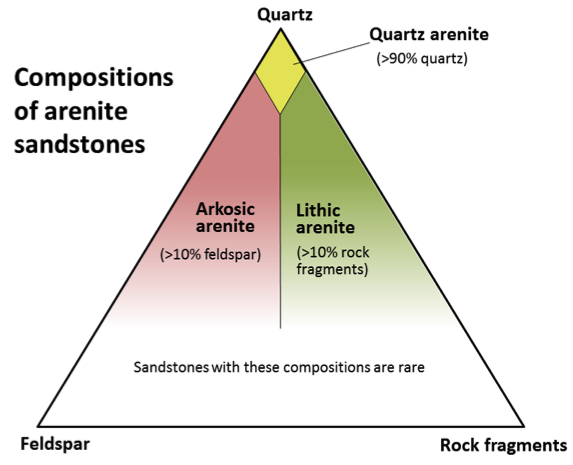

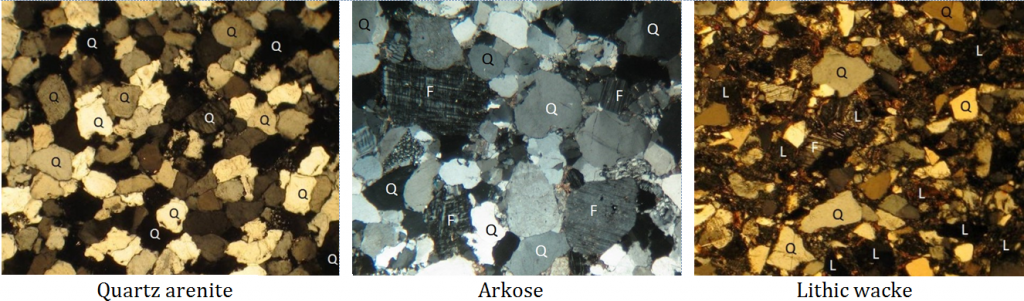

It’s worth taking a closer look at the different types of sandstone because sandstone is a common and important sedimentary rock. Typical sandstone compositions are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). Sandstones are mostly made up of sand grains of course, but they also include finer material—both silt and clay. The term arenite applies to a so-called clean sandstone, meaning one with less than 15% silt and clay. Considering the sand-sized grains only (the grains larger than 1/16th mm), arenites with 90% or more quartz are called quartz arenites. If they have more than 10% feldspar and more feldspar than rock fragments, they are called feldspathic arenites or arkosic arenites (or just arkose). If they have more than 10% rock fragments, and more rock fragments than feldspar, they are lithic arenites.[4] A sandstone with more than 15% silt or clay is called a wacke (pronounced wackie). The terms quartz wacke, lithic wacke, and feldspathic wacke are used with limits similar to those on the arenite diagram. Another name for a lithic wacke is greywacke.

Some examples of sandstones, magnified in thin section are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). (A thin section is rock sliced thin enough so that light can shine through.)

Clastic sedimentary rocks in which a significant proportion of the clasts are larger than 2 millimeters are known as conglomerate if the clasts are well rounded, and breccia if they are angular. Conglomerates form in high-energy environments such as fast-flowing rivers, where the particles can become rounded. Breccias typically form where the particles are not transported a significant distance in water, such as alluvial fans and talus slopes. Some examples of clastic sedimentary rocks are shown on Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).

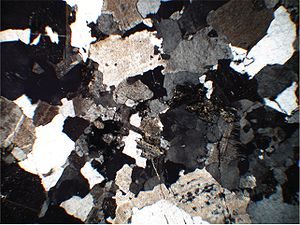

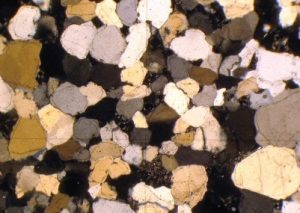

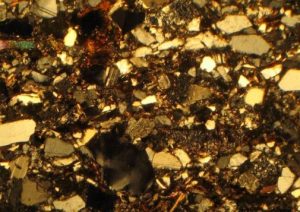

Table 6.3 below shows magnified thin sections of three sandstones, along with descriptions of their compositions. Using Table 6.1 and Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), find an appropriate name for each of these rocks.

| Magnified Thin Section | Description |

|---|---|

|

Angular sand-sized grains are approximately 85% quartz and 15% feldspar. Silt and clay make up less than 5% of the rock. |

|

Rounded sand-sized grains are approximately 99% quartz and 1% feldspar. Silt and clay make up less than 2% of the rock. |

|

Angular sand-sized grains are approximately 70% quartz, 20% lithic, and 10% feldspar. Silt and clay make up about 20% of the rock. |

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 6.2 answers.

Image Descriptions

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) image description: (A) Mudrock with bivalve impressions, Cretaceous Nanaimo group, Browns River, Vancouver Island. A very fine-grained rock with shell impressions. (B) Coarse sandstone with cross-bedding, Cambrian Tapeats Formation Chino Valley, Arizona. (C) Conglomerate with imbricate (aligned, tilted down to the left) cobbles, Cretaceous Geoffrey Formation, Hornby Island, BC. (D) Sedimentary breccia, the Pre-Cambrian Toby Formation, east of Castlegar, BC. [Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)]

Media Attributions

- Figures 6.1.1, 6.1.2, 6.1.3, 6.1.4, 6.1.5, 6.1.6, 6.1.7, 6.1.8: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Exercise 6.2, first image: Aplite Red © Rudolf Pohl. CC BY-SA.

- A micron is a millionth of a metre. There are 1,000 microns in a millimetre. ↵

- The largest known free-standing rock (i.e., not part of bedrock) is Giant Rock in the Mojave Desert, California. It’s about as big as an apartment building—seven stories high! ↵

- Discharge of a stream is the volume of flow passing a point per unit time. It’s normally measured in cubic meters per second (m3/s). ↵

- “Lithic” means “rock.” Lithic clasts are rock fragments, as opposed to mineral fragments. ↵