4.6: Volcanoes in British Columbia

- Page ID

- 7797

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

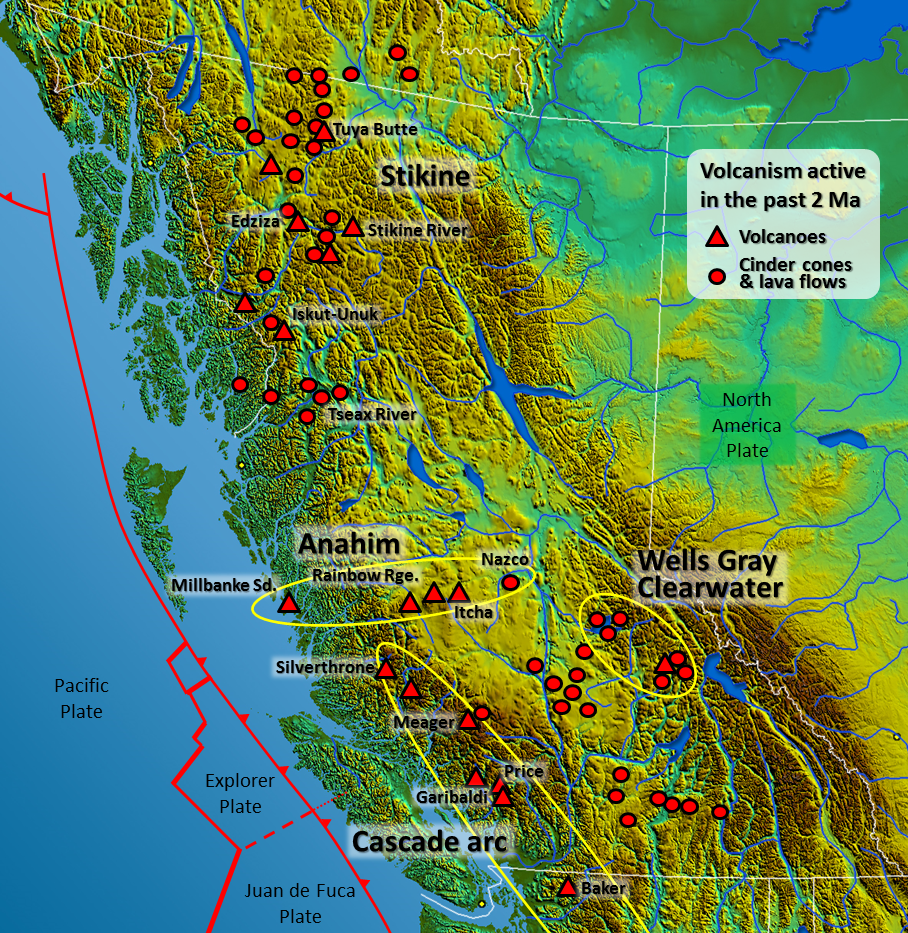

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)As shown on the Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), three types of volcanic environments are represented in British Columbia:

- The Cascade Arc (a.k.a. the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt in Canada) is related to subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate beneath the North America plate. This extends along the south coast from the U.S. border to the northern end of Vancouver Island.

- The Anahim Volcanic Belt is assumed to be related to a mantle plume. It is in central BC and stretches inland from the coast.

- The Stikine Volcanic Belt (northwestern BC) and the Wells Gray-Clearwater Volcanic Field (central Alberta border area) are assumed to be related to crustal rifting.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) Major volcanic centres in British Columbia active within the last 2 million years

Subduction Volcanism

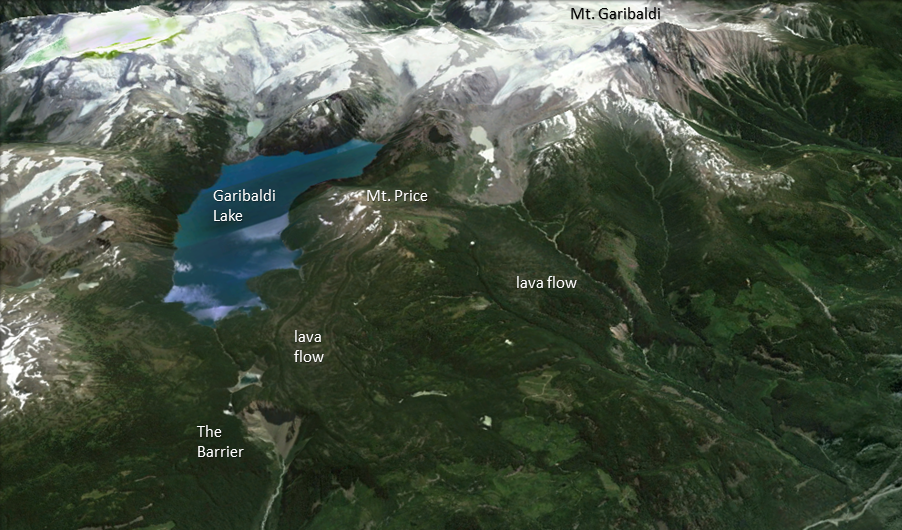

Southwestern British Columbia is at the northern end of the Juan de Fuca (Cascadia) subduction zone, and the volcanism there is related to magma generation by flux melting in the upper mantle above the subducting plate. In general, there has been a much lower rate and volume of volcanism in the B.C. part of this belt than in the U.S. part. One possible reason for this is that the northern part of the Juan de Fuca Plate (i.e., the Explorer Plate) is either not subducting, or is subducting at a slower rate than the rest of the plate. There are several volcanic centres in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt: the Garibaldi centre (including Mount Garibaldi and the Black Tusk-Mount Price area adjacent to Garibaldi Lake (Figures 4.0.1 and 4.0.2), Mount Cayley, and Mount. Meager (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The most recent volcanic activity in this area was at Mount Meager. Approximately 2,400 years ago, an explosive eruption of about the same magnitude as the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption took place at Mount Meager. Ash spread as far east as Alberta. There was also significant eruptive activity at Mounts Price and Garibaldi approximately 12,000 and 10,000 years ago during the last glaciation; in both cases, lava and tephra built up against glacial ice in the adjacent valley (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The Table in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) at the beginning of this chapter is a tuya, a volcano that formed beneath glacial ice and had its top eroded by the lake that formed around it in the ice.

Mantle Plume Volcanism

The chain of volcanic complexes and cones extending from Milbanke Sound to Nazko Cone is interpreted as being related to a mantle plume currently situated close to the Nazko Cone, just west of Quesnel. The North America Plate is moving in a westerly direction at about 2 cm per year with respect to this plume, and the series of now partly eroded shield volcanoes between Nazco and the coast is interpreted to have been formed by the plume as the continent moved over it.

The Rainbow Range, which formed at approximately 8 Ma, is the largest of these older volcanoes. It has a diameter of about 30 km and an elevation of 2,495 m (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The name “Rainbow” refers to the bright colors displayed by some of the volcanic rocks as they weather.

Rift-Related Volcanism

While B.C. is not about to split into pieces, two areas of volcanism are related to rifting—or at least to stretching-related fractures that might extend through the crust. These are the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field southeast of Quesnel, and the Northern Cordillera Volcanic Field, which ranges across the northwestern corner of the province (as already discussed in section 4.1). This area includes Canada’s most recent volcanic eruption, a cinder cone and mafic lava flow that formed around 250 years ago at the Tseax River Cone in the Nass River area north of Terrace. According to Nisga’a oral history, as many as 2,000 people died during that eruption, in which lava overran their village on the Nass River. Most of the deaths are attributed to asphyxiation from volcanic gases, probably carbon dioxide.

The Mount Edziza Volcanic Field near the Stikine River is a large area of lava flows, sulfurous ridges, and cinder cones. The most recent eruption in this area was about 1,000 years ago. While most of the other volcanism in the Edziza region is mafic and involves lava flows and cinder cones, Mount Edziza itself (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) is a composite volcano with rock compositions ranging from rhyolite to basalt. A possible explanation for the presence of composite volcanism in an area dominated by mafic flows and cinder cones is that there is a magma chamber beneath this area, within which magma differentiation is taking place.

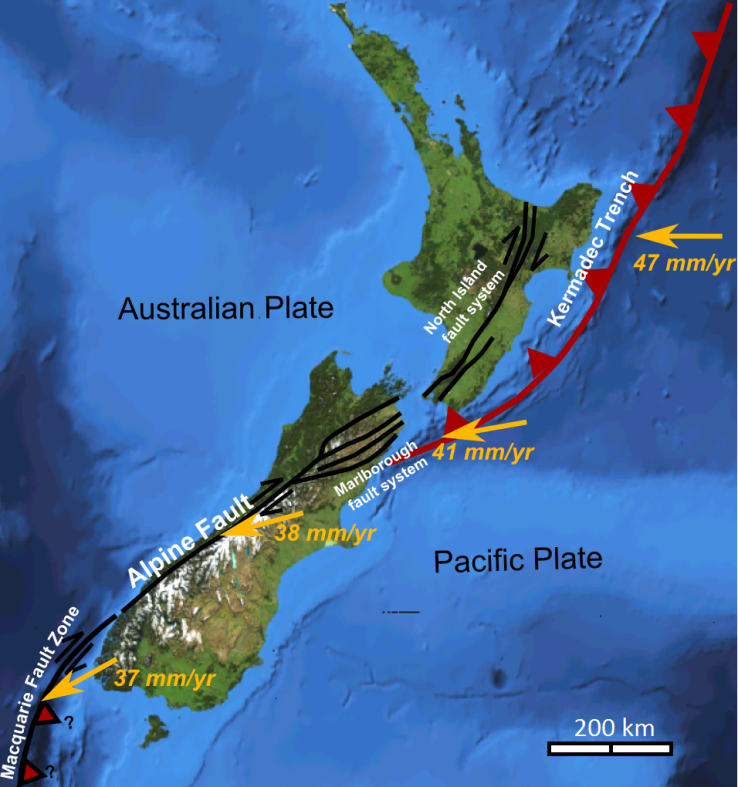

This map shows the plate tectonic situation in the area around New Zealand.

- Based on what you know about volcanoes in B.C., predict where you might expect to see volcanoes in and around New Zealand.

- What type of volcanoes would you expect to find in and around New Zealand?

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 4.7 Answers.

Media Attributions

- Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): “South-West Canada” by USGS. Public domain. Volcanic locations from Wood, D. (1993). Waiting for another big blast – probing B.C.’s volcanoes, Canadian Geographic, based on the work of Cathie Hickson.

- Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Photo from Google Earth. © Google. Edited by Steven Earle. Used with permission.

- Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): “Rainbow Range Colors” © nass5518. CC BY.

- Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): “Mount Edziza, British Columbia” © nass5518. CC BY.

- Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): “NZ Faults” © Mikenorton. CC BY-SA.