6.4.1: Summary - Silicate Minerals and Igneous Rocks

- Page ID

- 18941

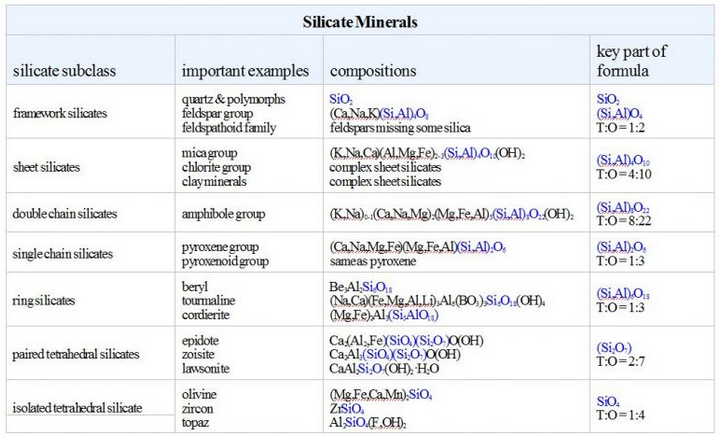

The table below lists the silicate minerals just considered. Quartz, at the very top of the table, has an Si:O ratio of 1:2. The ratio decreases downward in the table, and olivine, at the bottom of the list, has an Si:O ratio of 1:4. This reflects the fact that quartz is a felsic mineral and olivine is a mafic mineral. Things are a bit more complicated for minerals other than quartz and olivine because some Al commonly substitutes for some Si. But the ratio of Si plus the substituting Al (collectively called T) to oxygen increases from 1:2 at the top of the chart to 1:4 at the bottom. The key parts of the mineral formulae that show this are highlighted in blue in the table.

The left hand column in this table lists the silicate subclass, and the right hand column shows the ratio Si:O, or (Si,Al):O in a formula. So, the ratio tells us whether a silicate mineral is a framework, sheet, double chain, etc. All double chain silicates, for example, contain (Si,Al)8O22 in their formulas. Paired tetrahedral silicates contain Si2O7 in their formulas. Note that a few minerals, including epidote and zoisite, belong to more than one silicate subclass. Their formulas contain both SiO4 and Si2O7 and so they are partly paired tetrahedral silicates and partly isolated tetrahedral silicates.

Two caveats: Sometimes formulas are simplified by dividing by two or some other factor. For example, the pyroxene enstatite has formula Mg2Si2O6 but can also be written MgSiO3. It is the ratio (2:6 or 1:3) of Si:O tells us it is a single chain silicate. Also, sometimes subscripts are combined in formulas such as zoisite’s – it can be written Ca2Al3Si3O12(OH), which gives no hint about the way tetrahedra are polymerized.

| Accessory Minerals in Igneous Rocks | ||

| magnetite ilmenite apatite zircon titanite pyrite pyrrhotite allanite tourmaline sodalite fluorite |

Fe3O4 FeTiO3 Ca5(PO4)3(OH,F,Cl) ZrSiO4 CaTiSiO5 FeS2 Fe1-xS (Ca,Ce)2(Al,Fe)3Si3O12(OH) see formula in table above Na3Al3Si3O12•NaCl CaF2 |

|

This chapter focused on silicates, but igneous rocks often contain other minerals. The most common are listed in the table seen here. Most exist as accessory minerals because they are composed of rare elements or of elements that easily fit into other minerals. Magnetite and ilmenite, for example, are generally minor because they comprise elements that also easily fit into other more abundant essential minerals. Rocks that contain fluorine (F), zirconium (Zr), or phosphorus (P) may contain fluorite, zircon, or apatite, but F, Zr, and P are very minor elements in all but the most unusual rocks. Although not abundant, zircon often contains uranium and lead, which we may analyze to learn radiometric ages of igneous rocks.