11.8: Reading- Geologic Processes and Flowing Water

- Page ID

- 11576

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Streams—any running water from a rivulet to a raging river—complete the hydrologic cycle by returning precipitation that falls on land to the oceans (figure 1). Some of this water moves over the surface and some moves through the ground as groundwater. Flowing water does the work of both erosion and deposition.

Erosion and Deposition by Streams

Erosion by Streams

Flowing streams pick up and transport weathered materials by eroding sediments from their banks. Streams also carry ions and ionic compounds that dissolve easily in the water. Sediments are carried as:

- Dissolved load: Dissolved load is composed of ions in solution. These ions are usually carried in the water all the way to the ocean.

- Suspended load: Sediments carried as solids as the stream flows are suspended load. The size of particles that can be carried is determined by the stream’s velocity (figure 2). Faster streams can carry larger particles. Streams that carry larger particles have greater competence. Streams with a steep gradient (slope) have a faster velocity and greater competence.

Figure 2. Rivers carry sand, silt and clay as suspended load. During flood stage, the suspended load greatly increases as stream velocity increases. - Bed load: Particles that are too large to be carried as suspended load are bumped and pushed along the stream bed as bed load. Bed load sediments do not move continuously. This intermittent movement is called saltation. Streams with high velocities and steep gradients do a great deal of down cutting into the stream bed, which is primarily accomplished by movement of particles that make up the bed load.

- Here is a video of bedload transport.

Stages of Streams

As a stream flows from higher elevations, like in the mountains, towards lower elevations, like the ocean, the work of the stream changes. At a stream’s headwaters, often high in the mountains, gradients are steep (figure 3). The stream moves fast and does lots of work eroding the stream bed.

As a stream moves into lower areas, the gradient is not as steep. Now the stream does more work eroding the edges of its banks. Many streams develop curves in their channels called meanders (figure 4).

As the river moves onto flatter ground, the stream erodes the outer edges of its banks to carve a floodplain, which is a flat level area surrounding the stream channel (figure 5).

Base level is where a stream meets a large body of standing water, usually the ocean, but sometimes a lake or pond. Streams work to down cut in their stream beds until they reach base level. The higher the elevation, the farther the stream is from where it will reach base level and the more cutting it has to do.

Stream Deposition

As a stream gets closer to base level, its gradient lowers and it deposits more material than it erodes. On flatter ground, streams deposit material on the inside of meanders. Placer mineral deposits, described in the Earth’s Minerals chapter, are often deposited there. A stream’s floodplain is much broader and shallower than the stream’s channel. When a stream flows onto its floodplain, its velocity slows and it deposits much of its load. These sediments are rich in nutrients and make excellent farmland (figure 6).

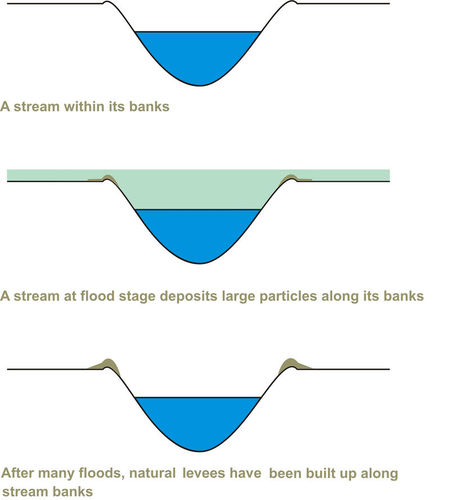

A stream at flood stage carries lots of sediments. When its gradient decreases, the stream overflows its banks and broadens its channel. The decrease in gradient causes the stream to deposit its sediments, the largest first. These large sediments build a higher area around the edges of the stream channel, creating natural levees (figure 7).

When a river enters standing water, its velocity slows to a stop. The stream moves back and forth across the region and drops its sediments in a wide triangular-shaped deposit called a delta (figure 8).

If a stream falls down a steep slope onto a broad flat valley, an alluvial fan develops (figure 9). Alluvial fans generally form in arid regions.

Contributors and Attributions

- 10.1: Water Erosion and Deposition. Provided by: CK-12. Located at: http://www.ck12.org/book/CK-12-Earth-Science-For-High-School/section/10.1/. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial