11.3: Reading- Phases of the Hydrologic Cycle

- Page ID

- 11571

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Because of the unique properties of water, water molecules can cycle through almost anywhere on Earth. The water molecule found in your glass of water today could have erupted from a volcano early in Earth history. In the intervening billions of years, the molecule probably spent time in a glacier or far below the ground. The molecule surely was high up in the atmosphere and maybe deep in the belly of a dinosaur. Where will that water molecule go next?

Three States of Water

Water is the only substance on Earth that is present in all three states of matter—as a solid, liquid or gas. (And Earth is the only planet where water is present in all three states.) Because of the ranges in temperature in specific locations around the planet, all three phases may be present in a single location or in a region. The three phases are solid (ice or snow), liquid (water), and gas (water vapor). See ice, water, and clouds (figure 2).

The Water Cycle

Because Earth’s water is present in all three states, it can get into a variety of environments around the planet. The movement of water around Earth’s surface is the hydrologic (water) cycle (figure 3).

Most of Earth’s water is stored in the oceans where it can remain for hundreds or thousands of years. The oceans are discussed in detail in the chapter Earth’s Oceans.

Water changes from a liquid to a gas by evaporation to become water vapor. The Sun’s energy can evaporate water from the ocean surface or from lakes, streams, or puddles on land. Only the water molecules evaporate; the salts remain in the ocean or a fresh water reservoir.

The water vapor remains in the atmosphere until it undergoes condensation to become tiny droplets of liquid. The droplets gather in clouds, which are blown about the globe by wind. As the water droplets in the clouds collide and grow, they fall from the sky as precipitation. Precipitation can be rain, sleet, hail, or snow. Sometimes precipitation falls back into the ocean and sometimes it falls onto the land surface.

For a little fun, watch this video. This water cycle song focuses on the role of the sun in moving H2O from one reservoir to another. The movement of all sorts of matter between reservoirs depends on Earth’s internal or external sources of energy:

This animation shows the annual cycle of monthly mean precipitation around the world.

When water falls from the sky as rain it may enter streams and rivers that flow downward to oceans and lakes. Water that falls as snow may sit on a mountain for several months. Snow may become part of the ice in a glacier, where it may remain for hundreds or thousands of years. Snow and ice may go directly back into the air by sublimation, the process in which a solid changes directly into a gas without first becoming a liquid. Although you probably have not seen water vapor sublimating from a glacier, you may have seen dry ice sublimate in air.

Snow and ice slowly melt over time to become liquid water, which provides a steady flow of fresh water to streams, rivers, and lakes below. A water droplet falling as rain could also become part of a stream or a lake. At the surface, the water may eventually evaporate and reenter the atmosphere.

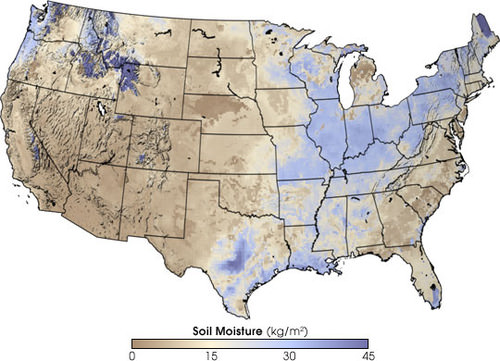

A significant amount of water infiltrates into the ground. Soil moisture is an important reservoir for water (figure 4). Water trapped in soil is important for plants to grow.

Water may seep through dirt and rock below the soil through pores infiltrating the ground to go into Earth’s groundwater system. Groundwater enters aquifers that may store fresh water for centuries. Alternatively, the water may come to the surface through springs or find its way back to the oceans.

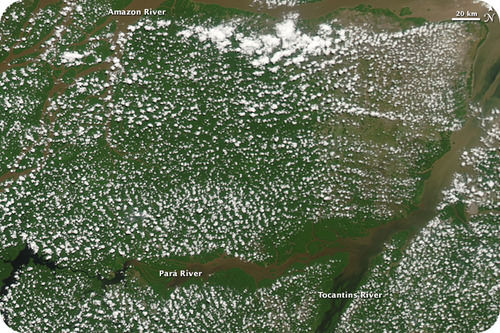

Plants and animals depend on water to live and they also play a role in the water cycle. Plants take up water from the soil and release large amounts of water vapor into the air through their leaves (figure 5), a process known as transpiration.

An online guide to the hydrologic cycle from the University of Illinois is found here.

People also depend on water as a natural resource. Not content to get water directly from streams or ponds, humans create canals, aqueducts, dams, and wells to collect water and direct it to where they want it (figure 6).

| Table 1. Water Use in the United States and Globally | ||

|---|---|---|

| Use | United States | Global |

| Agriculture | 34% | 70% |

| Domestic (drinking, bathing) | 12% | 10% |

| Industry | 5% | 20% |

| Power plant cooling | 49% | small |

It is important to note that water molecules cycle around. If climate cools and glaciers and ice caps grow, there is less water for the oceans and sea level will fall. The reverse can also happen.

How the water cycle works and how rising global temperatures will affect the water cycle, especially in California, are the topics of this Quest video. Learn more here.

Contributors and Attributions

- The Water Cycle. Provided by: CK-12. Located at: http://www.ck12.org/student/. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial