7.3: Reading- Stress In Earth’s Crust

- Page ID

- 11480

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Enormous slabs of lithosphere move unevenly over the planet’s spherical surface, resulting in earthquakes. This chapter deals with two types of geological activity that occur because of plate tectonics: mountain building and earthquakes. First, we will consider what can happen to rocks when they are exposed to stress.

Causes and Types of Stress

Stress is the force applied to an object. In geology, stress is the force per unit area that is placed on a rock. Four types of stresses act on materials.

- A deeply buried rock is pushed down by the weight of all the material above it. Since the rock cannot move, it cannot deform. This is called confining stress.

- Compression squeezes rocks together, causing rocks to fold or fracture (break) (figure 1). Compression is the most common stress at convergent plate boundaries.

- Rocks that are pulled apart are under tension. Rocks under tension lengthen or break apart. Tension is the major type of stress at divergent plate boundaries.

- When forces are parallel but moving in opposite directions, the stress is called shear (figure 2). Shear stress is the most common stress at transform plate boundaries.

When stress causes a material to change shape, it has undergone strain ordeformation. Deformed rocks are common in geologically active areas.

A rock’s response to stress depends on the rock type, the surrounding temperature, and pressure conditions the rock is under, the length of time the rock is under stress, and the type of stress.

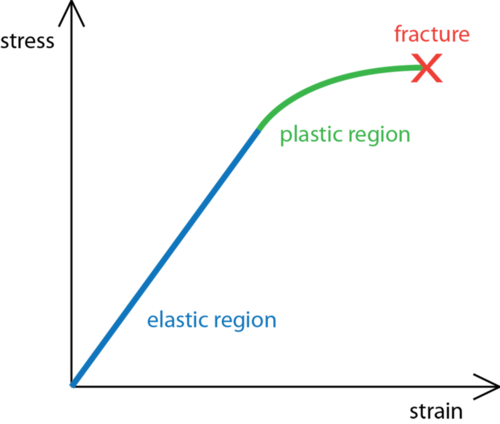

Rocks have three possible responses to increasing stress (illustrated in figure 3):

- elastic deformation: the rock returns to its original shape when the stress is removed.

- plastic deformation: the rock does not return to its original shape when the stress is removed.

- fracture: the rock breaks.

Under what conditions do you think a rock is more likely to fracture? Is it more likely to break deep within Earth’s crust or at the surface? What if the stress applied is sharp rather than gradual?

- At the Earth’s surface, rocks usually break quite quickly, but deeper in the crust, where temperatures and pressures are higher, rocks are more likely to deform plastically.

- Sudden stress, such as a hit with a hammer, is more likely to make a rock break. Stress applied over time often leads to plastic deformation.

Geologic Structures

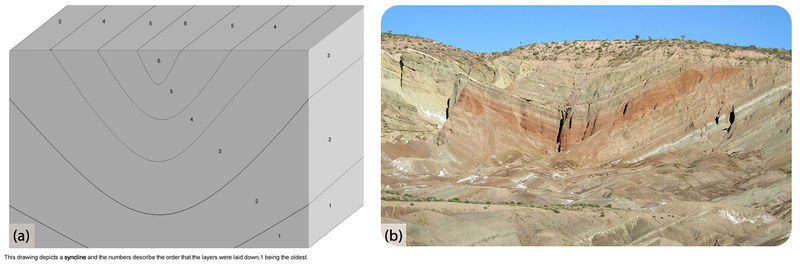

Sedimentary rocks are important for deciphering the geologic history of a region because they follow certain rules.

- Sedimentary rocks are formed with the oldest layers on the bottom and the youngest on top.

- Sediments are deposited horizontally, so sedimentary rock layers are originally horizontal, as are some volcanic rocks, such as ash falls.

- Sedimentary rock layers that are not horizontal are deformed.

You can trace the deformation a rock has experienced by seeing how it differs from its original horizontal, oldest-on-bottom position (figure 4a). This deformation produces geologic structures such as folds, joints, and faults that are caused by stresses (figure 4b). Using the rules listed above, try to figure out the geologic history of the geologic column below.

Folds

Rocks deforming plastically under compressive stresses crumple into folds (figure 5). They do not return to their original shape. If the rocks experience more stress, they may undergo more folding or even fracture.

Three types of folds are seen.

- Mononcline: A monocline is a simple bend in the rock layers so that they are no longer horizontal (see figure 6 for an example).

Figure 6. At Colorado National Monument, the rocks in a monocline plunge toward the ground. - Anticline: An anticline is a fold that arches upward. The rocks dip away from the center of the fold (figure 7). The oldest rocks are at the center of an anticline and the youngest are draped over them.

Figure 7. (a) Schematic of an anticline. (b) An anticline exposed in a road cut in New Jersey.

When rocks arch upward to form a circular structure, that structure is called a dome. If the top of the dome is sliced off, where are the oldest rocks located?

- Syncline: A syncline is a fold that bends downward. The youngest rocks are at the center and the oldest are at the outside (figure 8).

Figure 8. (a) Schematic of a syncline. (b) This syncline is in Rainbow Basin, California.

When rocks bend downward in a circular structure, that structure is called a basin (figure 9). If the rocks are exposed at the surface, where are the oldest rocks located?

Faults

A rock under enough stress will fracture. If there is no movement on either side of a fracture, the fracture is called a joint, as shown in (figure 10).

If the blocks of rock on one or both sides of a fracture move, the fracture is called a fault (figure 11). Sudden motions along faults cause rocks to break and move suddenly. The energy released is an earthquake.

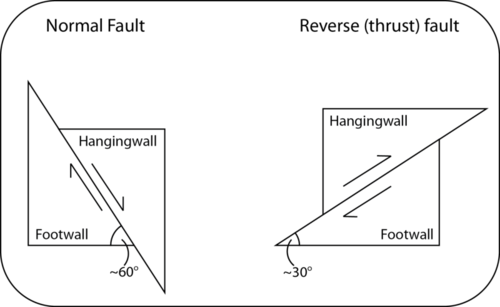

Slip is the distance rocks move along a fault. Slip can be up or down the fault plane. Slip is relative, because there is usually no way to know whether both sides moved or only one. Faults lie at an angle to the horizontal surface of the Earth. That angle is called the fault’s dip. The dip defines which of two basic types a fault is. If the fault’s dip is inclined relative to the horizontal, the fault is a dip-slip fault (figure 12). There are two types of dip-slip faults. In normal faults, the hanging wall drops down relative to the footwall. In reverse faults, the footwall drops down relative to the hanging wall.

Here is an animation of a normal fault.

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault in which the fault plane angle is nearly horizontal. Rocks can slip many miles along thrust faults (Figure 13).

Here is an animation of a thrust fault.

Normal faults can be huge. They are responsible for uplifting mountain ranges in regions experiencing tensional stress (figure 14).

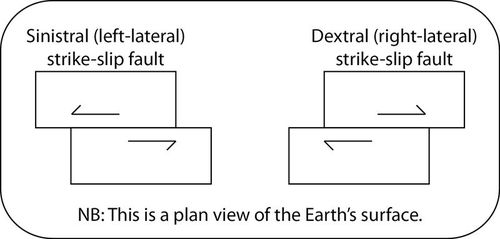

A strike-slip fault is a dip-slip fault in which the dip of the fault plane is vertical. Strike-slip faults result from shear stresses (figure 15).

California’s San Andreas Fault is the world’s most famous strike-slip fault. It is a right-lateral strike slip fault (figure 16).

Here is a strike-slip fault animation.

People sometimes say that California will fall into the ocean someday, which is not true. This animation shows movement on the San Andreas into the future.

Stress and Mountain Building

Two converging continental plates smash upwards to create mountain ranges (figure 17). Stresses from this uplift cause folds, reverse faults, and thrust faults, which allow the crust to rise upwards.

Subduction of oceanic lithosphere at convergent plate boundaries also builds mountain ranges (figure 18).

When tensional stresses pull crust apart, it breaks into blocks that slide up and drop down along normal faults. The result is alternating mountains and valleys, known as a basin-and-range (figure 19).

This is a very quick animation of movement of blocks in a basin-and-range setting.

Lesson Summary

- Stress is the force applied to a rock and may cause deformation. The three main types of stress are typical of the three types of plate boundaries: compression at convergent boundaries, tension at divergent boundaries, and shear at transform boundaries.

- Where rocks deform plastically, they tend to fold. Brittle deformation brings about fractures and faults.

- The two main types of faults are dip-slip (the fault plane is inclined to the horizontal) and strike-slip (the fault plane is perpendicular to the horizontal).

- The world’s largest mountains grow at convergent plate boundaries, primarily by thrust faulting and folding.

Contributors and Attributions

- 7.1: Stress in Earthu2019s Crust. Provided by: CK-12. Located at: http://www.ck12.org/book/CK-12-Earth-Science-For-High-School/section/7.1/. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial