2B Reverse Faults

- Page ID

- 1337

This page is a draft and is under active development.

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A reverse fault is a dip-slip fault where the hanging wall moves up relative to the foot wall. Reverse faults are generally recognized by the emplacement of older rocks above younger ones, though in areas of complex deformation this is not always the case. These faults often dip at low angles, generally lower than 30º, and so are called thrust faults. All thrust faults are also reverse faults.

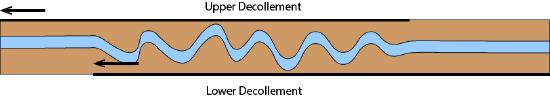

A decollement is a master fault at depth with a very gentle dip angle, usually less than 10º. In sedimentary basins, decollements tend to develop in weak rock horizons, such as shale or salt, where rocks can easily slide past one another. Many smaller faults often root into a single decollement.

Faults stepping up from one decollement to another form thrust ramps. Between decollements, ductile deformation may occur.

Fold and Thrust Belts

Numerous thrust faults in the upper plate that root into a single, gently dipping decollement. The lower plate, beneath the decollement, is not deformed internally.

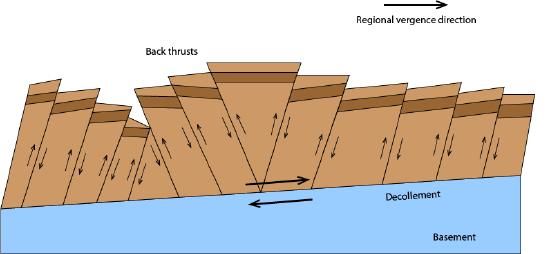

Vergence

The vergence is the direction of motion of the hanging wall of a thrust system. Vergence tends to be consistent in a set of thrusts, from the large scale of the overriding plate down to the microscale. In fold and thrust belts, vergence is often determined by looking at the orientations of imbricate faults, which generally dip toward the hinterland. In addition to identifying faults and their relative motion, facing direction of steep to overturned fold limbs is a common indicator of vergence. Sometimes, thrust faults develop with dips opposite of the regional vergence direction. These faults are called back thrusts, and they generally occur along thrust ramps.

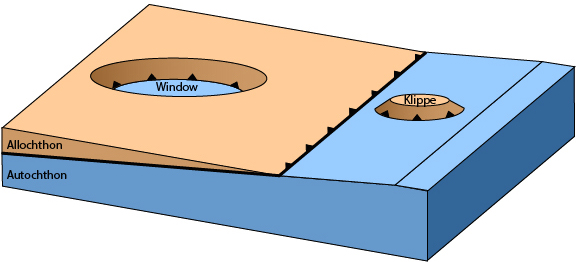

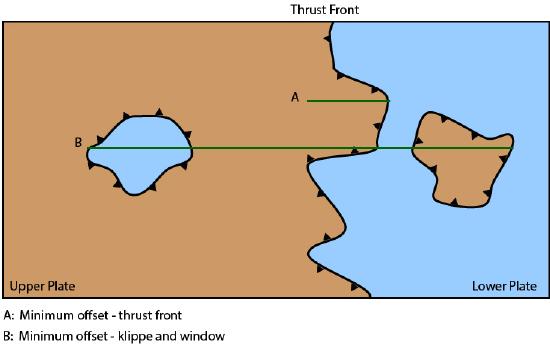

Klippe and Windows

A klippe is an island of a thrust sheet, isolated by erosion, perching on a portion of a thrust fault. The rocks making up the klippe are part of the allochthon, which is a set of exotic rocks transported into a region by faulting (in this case, as the upper plate of a thrust). A window is a portal eroded down through a thrust sheet, exposing the lower plate. Rocks exposed in a window are local rocks, called the autochthon.

Both of these features are important for constraining slip on large-offset thrust faults. Offsets measured from the back of a window to the front of a klippe give much better minimum estimates of total offset than simple measurements of the thrust front.

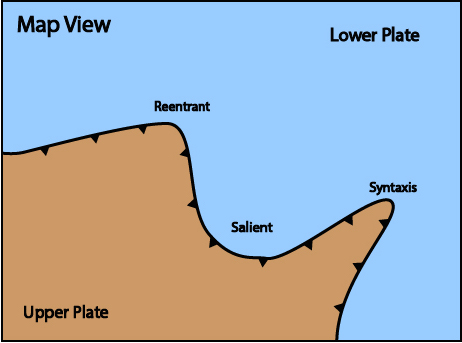

Salients and Reentrants

In map view, fold and thrust belts often have a cuspate thrust front. A cusp is known as a reentrant, though if very sharp it is instead termed a syntaxis. Areas between cusps are called salients. In these regions, the thrust belt is convex toward the foreland.

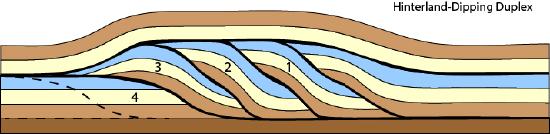

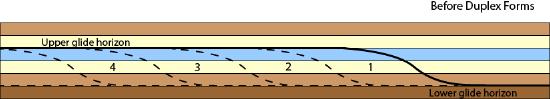

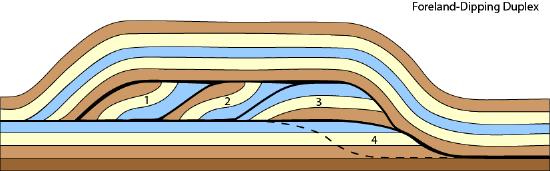

Duplexes

A duplex is a sliver or a collection of slivers of rock in a fault zone. Each sliver, known as a horse, is bounded by faults. The top of the duplex is bounded by a roof thrust and the bottom by a floor thrust. Duplexes commonly arise in response to fault slip over double bends and can take many different forms. In the figures below, the numbers 1-4 indicate the order of formation of each horse:

Note how the stacking of the horses is related to their order, as well as the shape of the resulting anticline.

Thick-Skinned Deformation

Thick-skinned deformation is characterized by steeply dipping reverse faults that do not root into a gently dipping decollement. This is the opposite of thin-skinned deformation, where thrust faults dominate. Steeply dipping thrust faults may form by reactivation of inherited normal or strike-slip faults. Reactivated faults are generally oblique to the shortening direction, leading to oblique-reverse faulting.

A blind thrust is a thrust fault that has not propagated to the surface and so can only be inferred from the folding they sometimes cause. These faults are particularly notorious for seismic hazards: the 1994 Northridge Earthquake, for example, occurred because of rupture on a blind thrust fault.

Summary

List of Terms

- Reverse fault

- Thrust fault

- Decollement

- Thrust ramp

- Vergence

- Back thrust

- Klippe

- Allochthon/allochthonous

- Window

- Autochthon/autochthonous

- Reentrant

- Syntaxis

- Duplex

- Horse

- Roof thrust

- Floor thrust

- Antiformal stack

- Foreland-dipping duplex

- Hinterland-dipping duplex

- Salient

- Thick-skinned deformation

- Thin-skinned deformation

- Blind thrust

Contributors

Michael E. Oskin (Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, UC Davis)