9.6: How fast is the vertical wind and which way does it blow?

- Page ID

- 3409

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

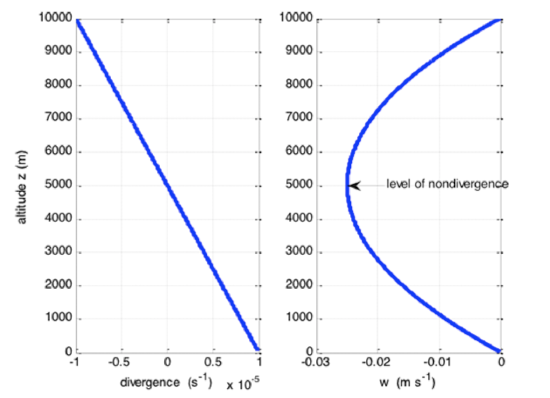

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)What are typical values of the vertical velocity caused by convergence or divergence and how do they vary with height? The vertical velocity, w, is typically too small to measure by a radiosonde. But we can estimate w from the convergence/divergence patterns:

\[\frac{\partial w}{\partial z}=-\vec{\nabla}_{H} \bullet \vec{U}_{H}=-\delta\]

Note that this equation just gives the derivative of the vertical velocity, not the vertical velocity itself. So to find the vertical velocity, we must integrate both sides of the equation over height, z.

Integrate this equation from the surface (z = 0) to some height z:

\[\int_{0}^{z} \frac{\partial w}{\partial z^{\prime}} d z^{\prime}=-\int_{0}^{z} \delta d z^{\prime}\]

\[w(z)=-\int_{0}^{z} \delta d z^{\prime}\]

where we have assumed that w(0) is equal to zero, which is true if the surface is horizontal. Equation [9.6] gives the kinematic vertical velocity.

To a good approximation, it has been determined that divergence/convergence for horizontal flow at large scales (e.g., synoptic scales, ~1000 km) varies linearly with altitude.

\[\delta=\delta_{s}+b z\]

where δs is the surface divergence and b is a constant. Substituting this expression for the horizontal divergence into Equation [9.6], we get:

\[w(z)=-\int_{0}^{z} \delta d z^{\prime}=-\delta_{s} z-\frac{1}{2} b z^{2}\]

The trick is to find b using some other information. To find b, note that \(\frac{\partial w}{\partial z}\) must be 0 at both Earth's surface and the tropopause, so the derivative is positive near Earth's surface. It must become negative at c tropopause in order for w to go to zero, and so somewhere in between, being positive and negative, it must be zero. We call this level the level of nondivergence, zLND,

\[0=-\delta_{s}-b z_{L N D}, \quad\) or \(\quad b=-\frac{\delta_{s}}{z_{L N D}}\]

\[w(z)=-\delta_{s} z+\frac{\delta_{s}}{2 z_{L N D}} z^{2}\]

The large-scale surface divergence typically has a value of 10–5 s–1. The large-scale level of nondivergence is typically about 5000 m. So,

\[b=-\frac{\delta_{s}}{z_{L N D}}=-\frac{10^{-5} \mathrm{s}^{-1}}{5000 \mathrm{m}}=-2 \times 10^{-9} \mathrm{m}^{-1} \mathrm{s}^{-1}\]

So, for typical large-scale surface divergence:

\[w(z)=\left(-10^{-5} \mathrm{s}^{-1}\right) z+\left(10^{-9} \mathrm{m}^{-1} \mathrm{s}^{-1}\right) z^{2}\]

At

\[z=z_{L N D}=5000 \mathrm{m}, w\left(z_{L N D}\right)=-2.5 \mathrm{cm} \mathrm{s}^{-1}=\left(-2.5 \times 10^{-5} \mathrm{km} \mathrm{s}^{-1}\right)\left(86400 \mathrm{s} \mathrm{day}^{-1}\right)=-2.2 \mathrm{km}\) day \(^{-1}\](see figure below).

The result is that w is only a few cm s–1. In a day, the air mass can rise or fall only a few kilometers. Compare this vertical motion dictated by large-scale convergence and divergence to the vertical motion in the core of a powerful thunderstorm (horizontal scale of a few km), where the vertical velocities can be many m s–1. This simple model is called the bowstring model because the shape of the vertical velocity looks like a bowstring that is fixed at two points but can vary as a parabola in between.

Credit: W. Brune

Quiz 9-2: Connecting the dots with vertical motion.

- Find Practice Quiz 9-2 in Canvas. You may complete this practice quiz as many times as you want. It is not graded, but it allows you to check your level of preparedness before taking the graded quiz.

- When you feel you are ready, take Quiz 9-2. You will be allowed to take this quiz only once. Good luck!