6.8: Fog

- Page ID

- 9935

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)6.8.1. Types

Fog is a cloud that touches the ground. The main types of fog are:

- upslope

- radiation

- advection

- precipitation or frontal

- steam

They differ in how the air becomes saturated.

Upslope fog is formed by adiabatic cooling in rising air that is forced up sloping terrain by the wind. Namely, it is formed the same way as clouds. As already discussed in the Water Vapor chapter, air parcels must rise or be lifted to their lifting condensation level (LCL) to form a cloud or upslope fog.

Radiation fog and advection fog are formed by cooling of the air via conduction from the cold ground. Radiation fog forms during clear, nearlycalm nights when the ground cools by IR radiation to space. Advection fog forms when initially-unsaturated air advects over a colder surface.

Precipitation fog or frontal fog is formed by adding moisture, via the evaporation from warm rain drops falling down through the initially-unsaturated cooler air below cloud base.

Steam fog occurs when cold air moves over warm humid surfaces such as unfrozen lakes during early winter. The lake warms the air near it by conduction, and adds water by evaporation. However, this thin layer of moist warm air near the surface is unsaturated. As turbulence causes it to mix with the colder air higher above the surface, the mixture becomes saturated, which we see as steam fog.

6.8.2. Idealized Fog Models

By simplifying the physics, we can create mathematical fog models that reveal some of the fundamental behaviors of different types of fog.

6.8.2.1. Advection Fog

For formation and growth of advection fog, suppose a fogless mixed layer of thickness zi advects with speed M over a cold surface such as snow covered ground or a cold lake. If the surface potential temperature is θsfc, then the air potential temperature θ cools with downwind distance according to

\(\ \begin{align} \theta=\theta_{s f c}+\left(\theta_{o}-\theta_{s f c}\right) \cdot \exp \left(-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \cdot x\right)\tag{6.8}\end{align}\)

where θo is the initial air potential temperature, CH is the heat transfer coefficient (see the Heat Budgets chapter), and x is travel distance over the cold surface. This assumes an idealized situation where there is sufficient turbulence caused by a brisk wind speed to keep the boundary layer well mixed.

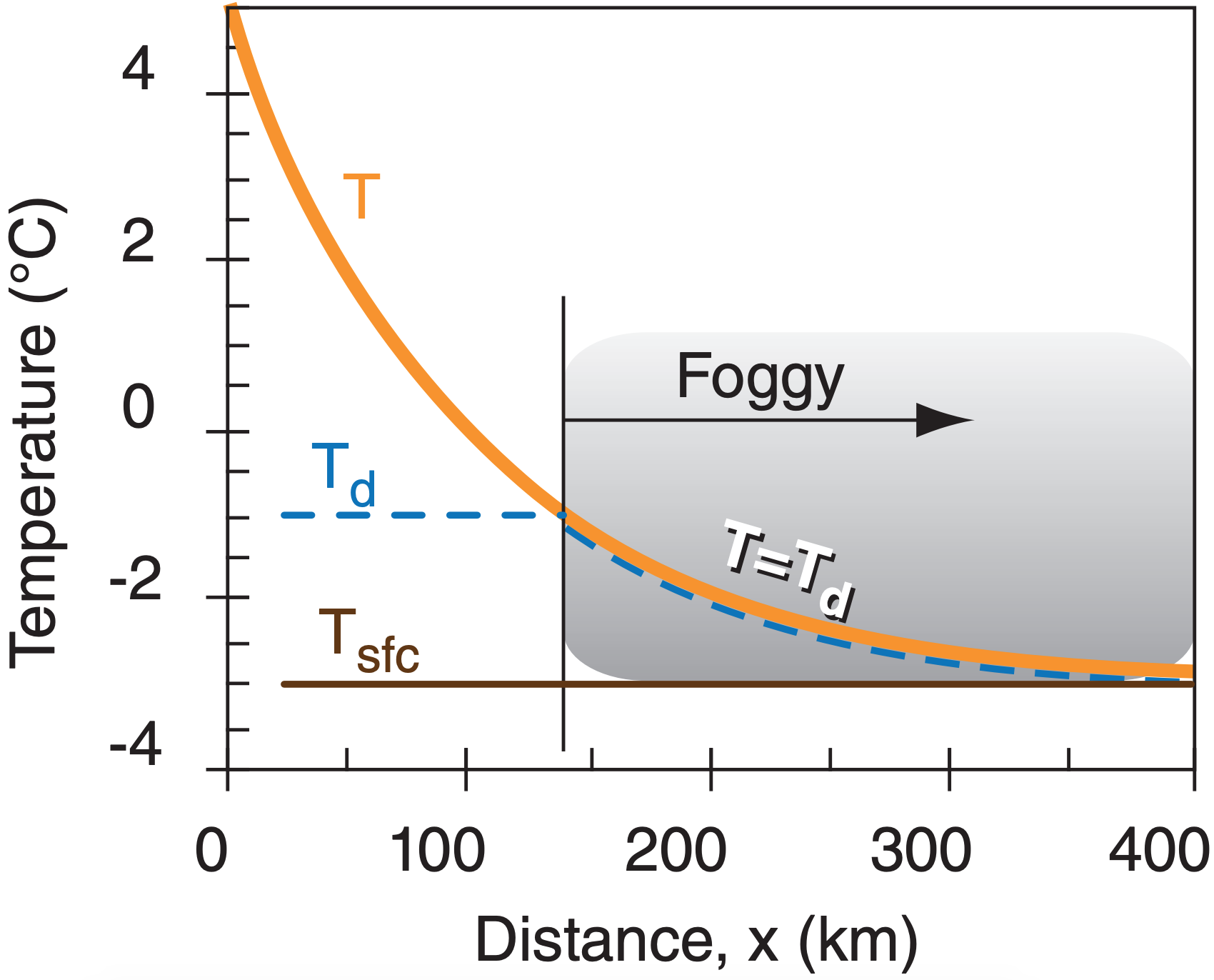

Advection fog forms when the temperature drops to the dew-point temperature Td. At the surface (more precisely, at z = 10 m), θ ≈ T . Thus, setting θ ≈ T = Td at saturation and solving the equation above for x gives the distance over the lake at which fog first forms:

\(\ \begin{align} x=\dfrac{z_{i}}{C_{H}} \cdot \ln \left(\dfrac{T_{o}-T_{s f c}}{T_{d}-T_{s f c}}\right)\tag{6.9}\end{align}\)

Surprisingly, neither the temperature evolution nor the distance to fog formation depends on wind speed.

For example, advection fog can exist along the California coast where warm humid air from the west blows over the cooler “Alaska current” coming from further north in the Pacific Ocean.

Advection fog, once formed, experiences radiative cooling from fog top. Such cooling makes the fog more dense and longer lasting as it can evolve into a well-mixed radiation fog, described in the next subsection.

Dissipation of advection fog is usually controlled by the synoptic and mesoscale weather patterns. If the surface becomes warmer (e.g., all the snow melts, or there is significant solar heating), or if the wind changes direction, then the conditions that originally created the advection fog might disappear. At that point, dissipation depends on the same factors that dissipate radiation fog. Alternately, frontal passage or change of wind direction might blow out the advection fog, and replace the formerly-foggy air with cold dry air that might not be further cooled by the underlying surface.

Sample Application

Fog formation: A layer of air adjacent to the surface (where P = 100 kPa) is initially at temperature 20°C and relative humidity 68%. (a) To what temperature must this layer be cooled to form radiation or advection fog? (b) To what altitude must this layer be lifted to form upslope fog? (c) How much water must be evaporated into each kilogram of dry air from falling rain drops to form frontal fog? (d) How much evaporation (mm of lake water depth) from the lake is necessary to form steam fog throughout a 100 m thick layer? [Hint: Use eqs. from the Water Vapor chapter.]

Find the Answer

Given: P = 100 kPa, T = 20°C, RH = 68%, ∆z = 100 m

Find: a) Td=?°C, b) zLCL=?m, c) rs=?g kg–1 d) d=?mm

Using Table 4-1: es = 2.371 kPa.

Using eq. (4.14): e = (RH/100%)·es = (68%/100%)·( 2.371 kPa) = 1.612 kPa

(a) Knowing e and using Table 4-1: Td = 14°C.

(b) Using eq. (4.16):

zLCL = a· [T – Td] = (0.125 m K–1)· [(20+273)K – (14+273)K] = 0.75 km

(c) Using eq. (4.4), the initial state is:

r = ε·e/(P–e) = 0.622 · (1.612 kPa) / (100 kPa – 1.612 kPa) = 0.0102 g g–1 = 10.2 g kg–1

The final mixing ratio at saturation (eq. 4.5) is:

rs = ε·es /(P–es) = 0.622·(2.371 kPa) / (100 kPa – 2.371 kPa) = 0.0151 g g–1 = 15.1 g kg–1.

The amount of additional water needed is

∆r = rs – r = 15.1 – 10.2 = 4.9 gwater kgair–1

(d) Using eqs. (4.11) & (4.13) to find absolute humidity

ρv = ε · e· ρd / P = (0.622)·(1.612 kPa)·(1.275 kg·m–3)/(100 kPa) = 0.01278 kg·m–3

ρvs = ε · es· ρd / P = (0.622)·(2.371 kPa)·(1.275 kg·m–3)/(100 kPa) = 0.01880 kg·m–3

The difference must be added to the air to reach saturation: ∆ρ = ρvs – ρv = ∆ρ = (0.01880–0.01278) kg·m–3 = 0.00602 kg·m–3

But over A =1 m2 of surface area, air volume is

Volair =A · ∆z = (1 m2)·(100 m) = 100 m3.

The mass of water needed in this volume is

m = ∆ρ · Volair = 0.602 kg of water.

But liquid water density ρliq = 1000 kg·m–3: Thus,

Volliq = m / ρliq = 0.000602 m3

The depth of liquid water under the 1 m2 area is

d = Volliq / A = 0.000602 m = 0.602 mm

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: For many real fogs, cooling of the air and addition of water via evaporation from the surface happen simultaneously. Thus, a fog might form in this example at temperatures warmer than 14°C.

Derivation of eq. (6.8):

Start with the Eulerian heat balance, neglecting all contributions except for turbulent flux divergence:

\(\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial t}=-\dfrac{\partial F_\text

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Meteorology_and_Climate_Science/Practical_Meteorology_(Stull)/06:_Clouds/6.08:_Fog), /content/body/div[2]/div[1]/div[2]/div/p[3]/span, line 1, column 3

where θ is potential temperature, and F is heat flux. For a mixed layer of fog, F is linear with z, thus:

\(\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial t}=-\dfrac{F_\text{z turb zi}(\theta)-F_\text{z turb sfc}(\theta)}{z_{i}-0}\)

If entrainment at the top of the fog layer is small, then Fz turb zi(θ) = 0, leaving:

\(\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial t}=\dfrac{F_\text {z turb sfc}(\theta)}{z_{i}}=\dfrac{F_{H}}{z_{i}}\)

Estimate the flux using bulk transfer eq. (3.21). Thus:

\(\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial t}=\dfrac{C_{H} \cdot M \cdot\left(\theta_{s f c}-\theta\right)}{z_{i}}\)

If the wind speed is roughly constant with height, then let the Eulerian volume move with speed M:

\(\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial t}=\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial x} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial t}=\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial x} \cdot M\)

Plugging this into the LHS of the previous eq. gives:

\(\dfrac{\partial \theta}{\partial x}=\dfrac{C_{H} \cdot\left(\theta_{s f c}-\theta\right)}{z_{i}}\)

To help integrate this, define a substitute variable s = θ – θsfc , for which ∂s = ∂θ . Thus:

\(\dfrac{\partial S}{\partial x}=-\dfrac{C_{H} \cdot s}{z_{i}}\)

Separate the variables: \(\dfrac{d s}{s}=-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} d x\)

Which can be integrated (using the prime to denote a dummy variable of integration):

\(\int_{s^{\prime}=s_{0}}^{s} \dfrac{d s^{\prime}}{s^{\prime}}=-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \int_{x^{\prime}=0}^{x} d x^{\prime}\)

Yielding:

\(\ln (s)-\ln \left(s_{o}\right)=-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \cdot(x-0)\)

or

\(\ln \left(\dfrac{s}{s_{o}}\right)=-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \cdot x\)

Taking the antilog of each side (i.e., exp):

\(\dfrac{s}{s_{o}}=\exp \left(-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \cdot x\right)\)

Upon rearranging, and substituting for s:

\(\theta-\theta_{s f c}=\left(\theta-\theta_{s f c}\right)_{o} \cdot \exp \left(-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \cdot x\right)\)

But θsfc is assumed constant, thus:

\(\ \begin{align} \theta=\theta_{s f c}+\left(\theta_{o}-\theta_{s f c}\right) \cdot \exp \left(-\dfrac{C_{H}}{z_{i}} \cdot x\right)\tag{6.8}\end{align}\)

Sample Application

Air of initial temperature 5°C and depth 200 m flows over a frozen lake of surface temperature –3°C. If the initial dew point of the air is –1°C, how far from shore will advection fog first form?

Find the Answer

Given: To = 5°C, Td = –1°C, Tsfc = –3 °C, zi =200 m

Find: x = ? km.

Assume smooth ice: CH = 0.002 .

Use eq. (6.9): x = (200 m/0.002)· ln[(5–(–3))/(–1–(–3))] = 138.6 km

Sketch, where eq. (6.8) was solved for T vs. x:

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: If the lake is smaller than 138.6 km in diameter, then no fog forms. Also, if the dew-point temperature needed for fog is colder than the surface temperature, then no fog forms.

6.8.2.2. Radiation Fog

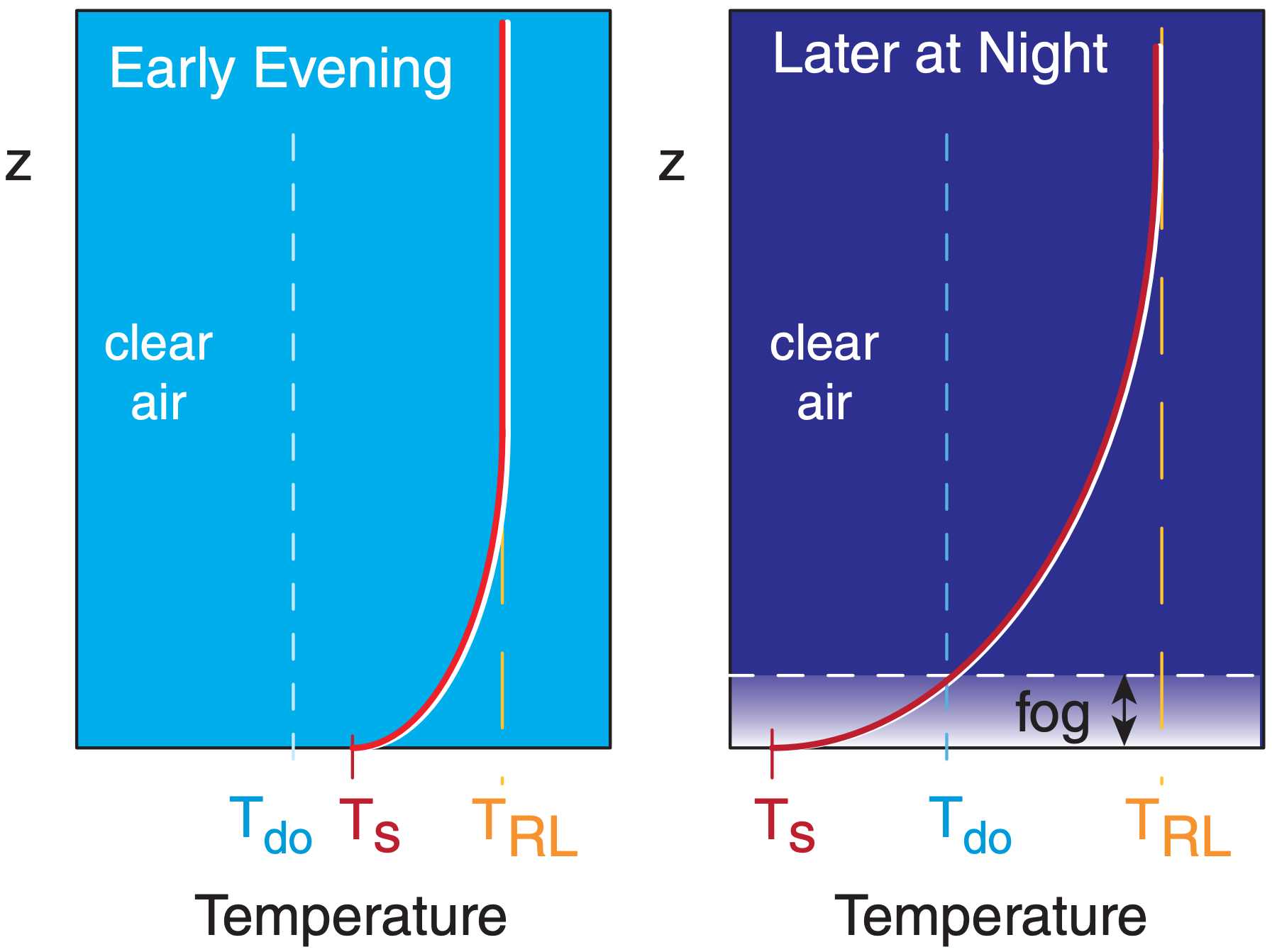

For formation and growth of radiation fog, assume a stable boundary layer forms and grows, as given in the Atmospheric Boundary Layer chapter. For simplicity, assume that the ground is flat, so there is no drainage of cold air downhill (a poor assumption). If the surface temperature Ts drops to the dew-point temperature Td then fog can form (Fig. 6.13). The fog depth is the height where the nocturnal temperature profile crosses the initial dew-point temperature Tdo.

The time to between when nocturnal cooling starts and the onset of fog is

\(\ \begin{align} t_{o}=\dfrac{a^{2} \cdot M^{3 / 2} \cdot\left(T_{R L}-T_{d}\right)^{2}}{\left(-F_{H}\right)^{2}}\tag{6.10}\end{align}\)

where a = 0.15 m1/4·s1/4 , TRL is the residual-layer temperature (extrapolated adiabatically to the surface), M is wind speed in the residual layer, and FH is the average surface kinematic heat flux. Faster winds and drier air delay the onset of fog. For most cases, fog never happens because night ends first.

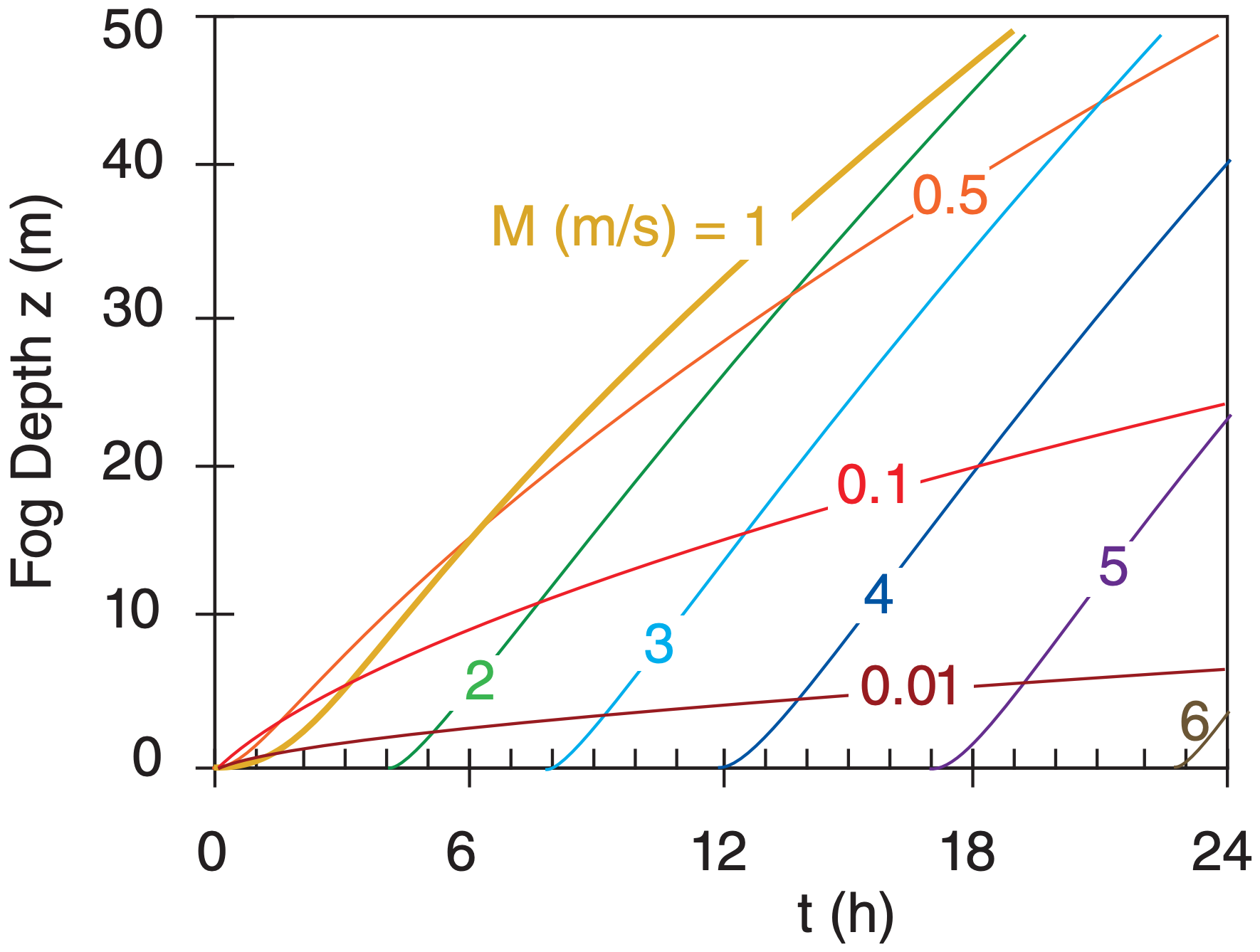

Once fog forms, evolution of its depth is approximately

\(\ \begin{align} z=a \cdot M^{3 / 4} \cdot t^{1 / 2} \cdot \ln \left[\left(t / t_{o}\right)^{1 / 2}\right]\tag{6.11}\end{align}\)

where to is the onset time from the previous equation. This equation is valid for t > to.

Liquid water content increases as a saturated air parcel cools. Also, visibility decreases as liquid water increases. Thus, the densest (lowest visibility) part of the fog will generally be in the coldest air, which is initially at the ground.

Sample Application

Given a residual layer temperature of 20°C, dew point of 10°C, and wind speed 1 m s–1. If the surface kinematic heat flux is constant during the night at –0.02 K·m s–1, then what is the onset time and height evolution of radiation fog?

Find the Answer

Given: TRL = 20°C, Td = 10°C, M = 1 m s–1, FH = –0.02 K·m s–1

Find: to = ? h, and z vs. t.

Use eq. (6.10):

\(\begin{aligned} t_{O} &=\dfrac{\left(0.15 \mathrm{m}^{1 / 4} \cdot \mathrm{s}^{1 / 4}\right)^{2} \cdot(1 \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s})^{3 / 2} \cdot\left(20-10^{\circ} \mathrm{C}\right)^{2}}{\left(0.02^{\circ} \mathrm{C} \cdot \mathrm{m} / \mathrm{s}\right)^{2}} =1.563 \mathrm{h} \end{aligned}\)

The height evolution for this wind speed, as well as for other wind speeds, is calculated using eq. (6.11):

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: Windier nights cause later onset of fog, but stimulates rapid growth of the fog depth.

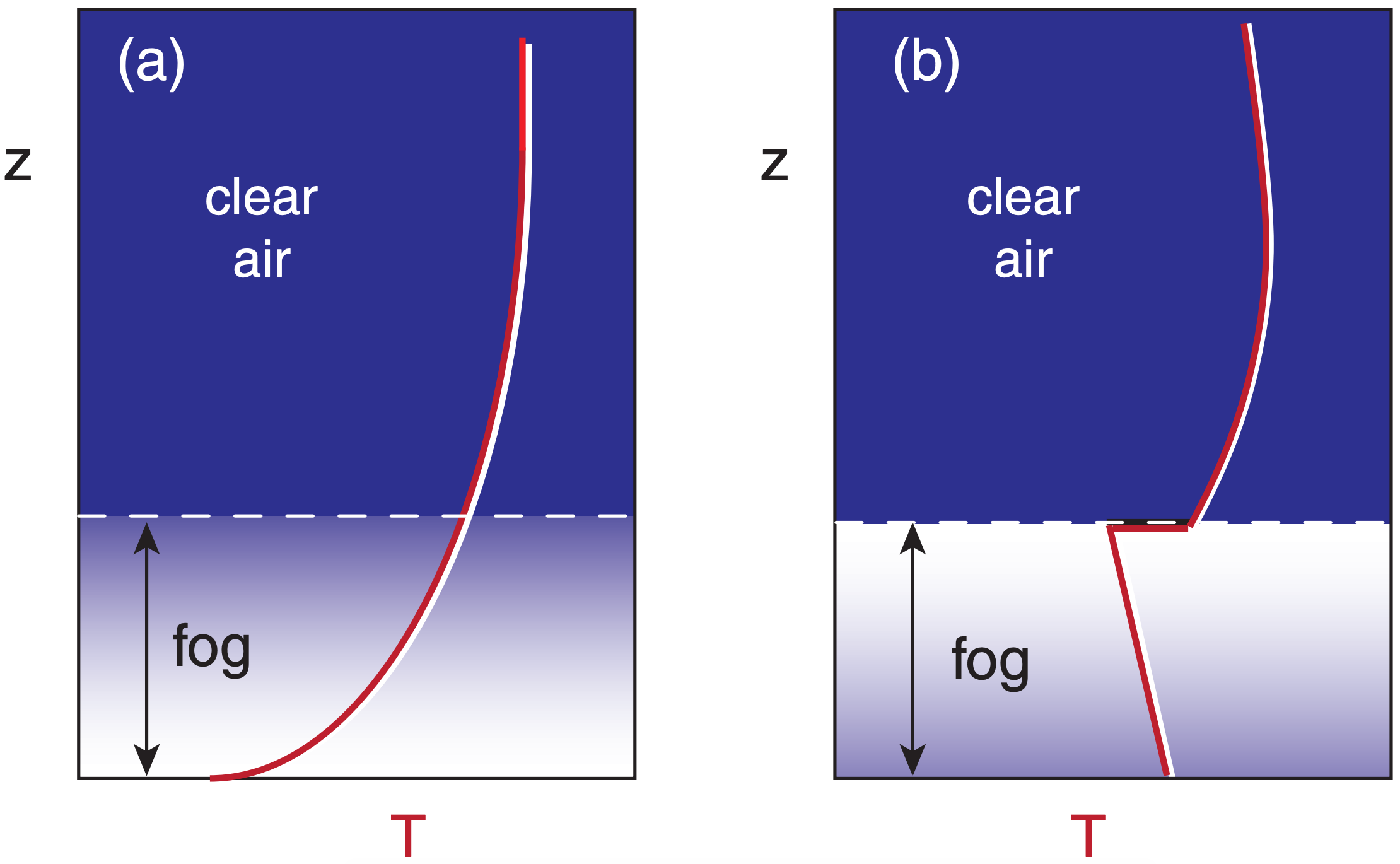

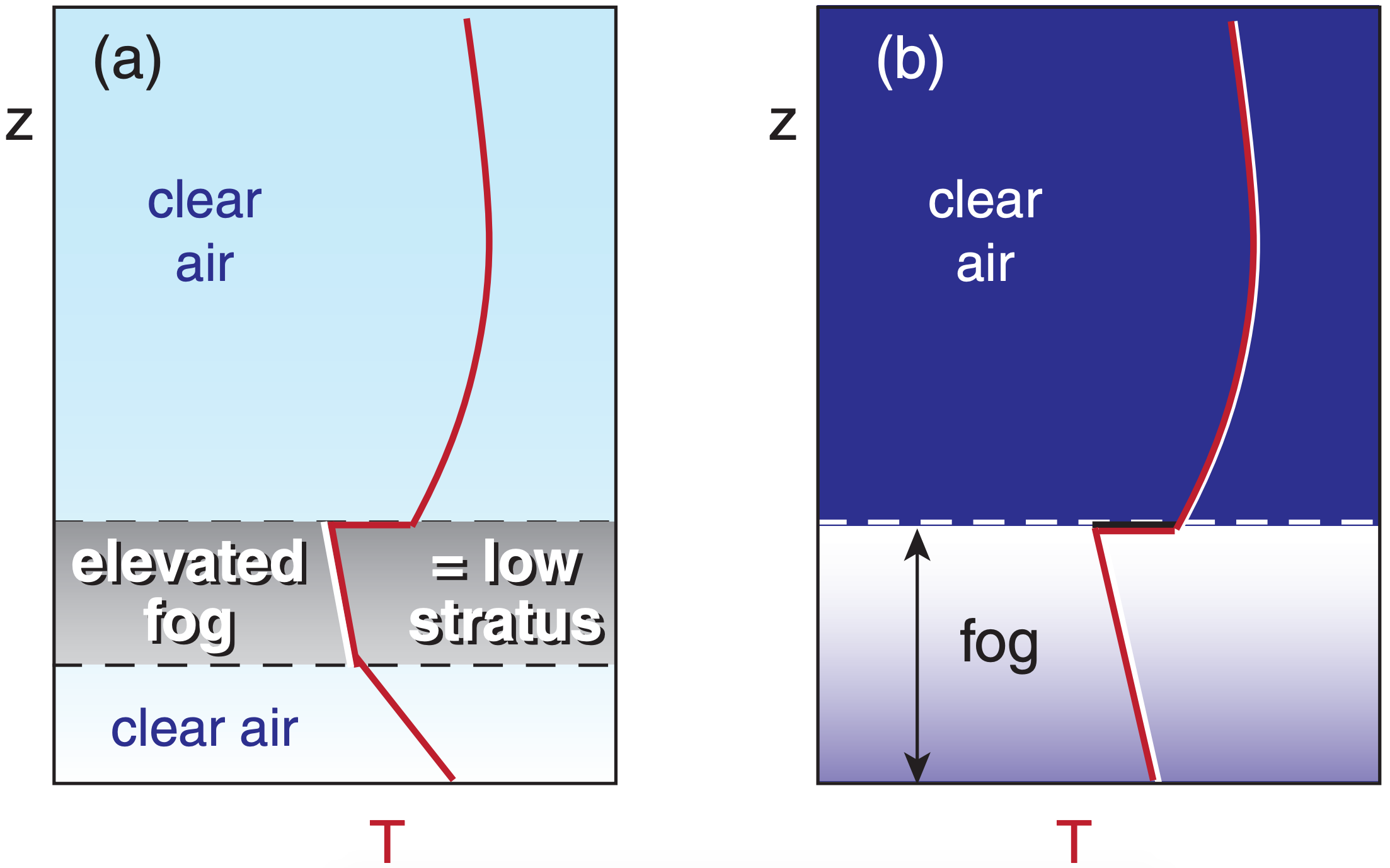

Initially, fog density decreases smoothly with height because temperature increases smoothly with height (Fig. 6.14a). As the fog layer becomes optically thicker and more dense , it reaches a point where the surface is so obscured that it can no longer cool by direct IR radiation to space.

Instead, the height of maximum radiative cooling moves upward into the fog away from the surface. Cooling of air within the nocturnal fog causes air to sink as cold thermals. Convective circulations then turbulently mix the fog.

Very quickly, the fog changes into a well-mixed fog with wet-bulb-potential temperature θW and total-water content rT that are uniform with height. During this rapid transition, total heat and total water averaged over the whole fog layer are conserved. As the night continues, θW decreases and rL increases with time due to continued radiative cooling.

In this fog the actual temperature decreases with height at the moist adiabatic lapse rate (Fig. 6.14b), and liquid water content increases with height. Continued IR cooling at fog top can strengthen and maintain this fog. This fog is densest near the top of the fog layer.

6.8.2.3. Dissipation of Well-Mixed (Radiation and Advection) Fogs

During daytime, solar heating and IR cooling are both active. Fogs can become less dense, can thin, can lift, and can totally dissipate due to warming by the sun.

Stratified fogs (Fig. 6.14a) are optically thin enough that sunlight can reach the surface and warm it. The fog albedo can be in the range of A = 0.3 to 0.5 for thin fogs. This allows the warm ground to rapidly warm the fog layer, causing evaporation of the liquid drops and dissipation of the fog.

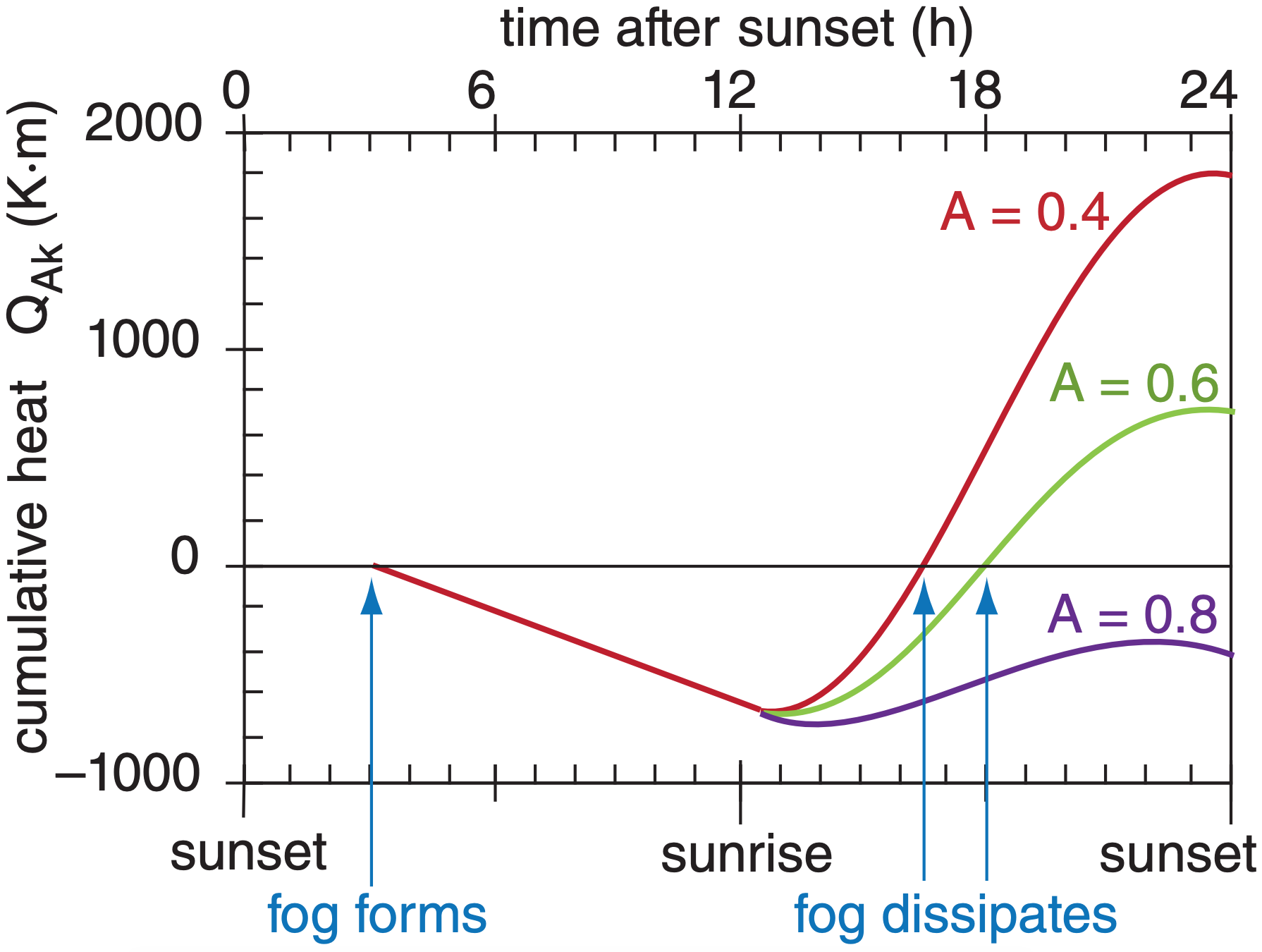

For optically-thick well-mixed fogs (Fig. 6.14b), albedoes can be A =0.6 to 0.9. What little sunlight is not reflected off the fog is absorbed in the fog itself. However, IR radiative cooling continues, and can compensate the solar heating. One way to estimate whether fog will totally dissipate at time t in the future is to calculate the sum QAk of accumulated cooling and heating (see the Atmospheric Boundary Layer chapter) during the time period (t – to) since the fog first formed:

\(\begin{align} Q_{A k}=F_{H . n i g h t} \cdot\left(t-t_{o}\right)+(1-A) \cdot \dfrac{F_{H . \max } \cdot D}{\pi} \cdot\left[1-\cos \left(\dfrac{\pi \cdot\left(t-t_{S R}\right)}{D}\right)\right] \tag{6.12}\end{align}\)

where FH.night is average nighttime surface kinematic heat flux (negative at night), and FH.max is the amplitude of the sine wave that approximates surface kinematic sensible heat flux due to solar heating (i.e., the positive value of insolation at local noon). D is daylight duration hours, t is hours after sunset, to is hours after sunset when fog first forms, and tSR is hours between sunset and the next sunrise.

The first term on the right should be included only when t > to, which includes not only nighttime when the fog originally formed, but the following daytime also. This approach assumes that the rate FH.night of IR cooling during the night is a good approximation to the continued IR cooling during daytime.

The second term should be included only when t > tSR, where tSR is sunrise time. (See the Atmospheric Boundary Layer Chapter for definitions of other variables). If there was zero fog initially, but fog forms during the night as QAk becomes negative, then that fog will dissipate after sunrise at a time when QAk first becomes positive (neglecting other factors such as advection). This is illustrated in the figure in the Sample Application box at right.

While IR cooling happens from the very top of the fog, solar heating occurs over a greater depth in the top of the fog layer. Such heating underneath cooling statically destabilizes the fog, creating convection currents of cold thermals that sink from the fog top. These upside-down cold thermals continue to mix the fog even though there might be net heating when averaged over the whole fog. Thus, any radiatively heated or cooled air is redistributed and mixed vertically throughout the fog by convection.

Such heating can cause the bottom part of the fog to evaporate, which appears to an observer as lifting of the fog (Fig. 6.15a). Sometimes the warming during the day is insufficient to evaporate all the fog. When night again occurs and radiative cooling is not balanced by solar heating, the bottom of the elevated fog lowers back down to the ground (Fig. 6.15b).

In closing this section on fogs, please be aware that the equations above for formation, growth, and dissipation of fogs were based on very idealized situations, such as flat ground and horizontally uniform heating and cooling. In the real atmosphere, even gentle slopes can cause katabatic drainage of cold air into the valleys and depressions (see the Regional Winds chapter), which are then the favored locations for fog formation. The equations above were meant only to illustrate some of the physical processes, and should not to be used for operational fog forecasting.

Sample Application

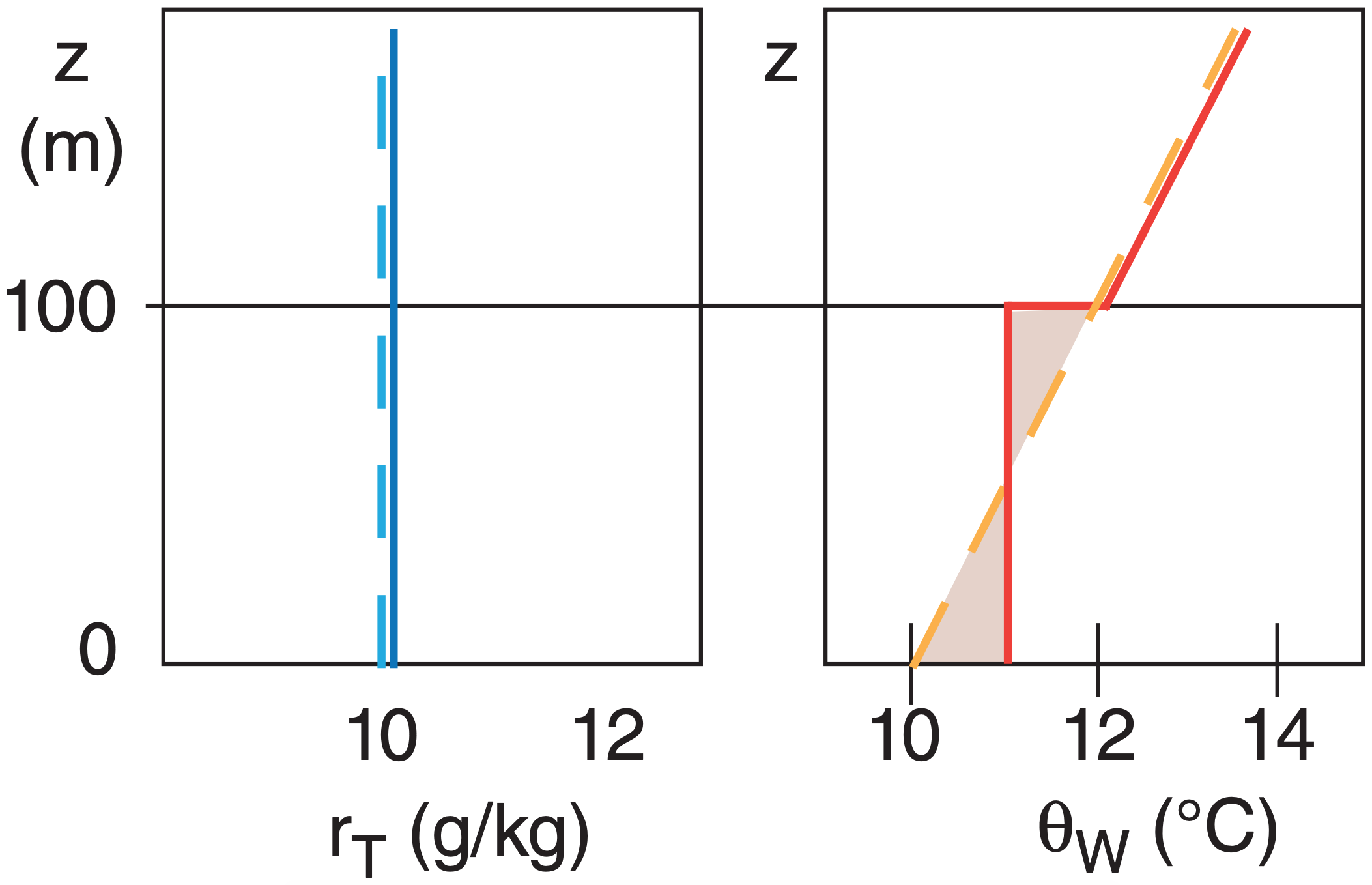

Initially, total water is constant with height at 10 g kg–1, and wet-bulb potential temperature increases with height at rate 2°C/100m in a stratified fog. Later, a well-mixed fog forms with depth 100 m. Plot the total water and θW profiles before and after mixing.

Find the Answer

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: Dashed lines show initial profiles, solid are final profiles. For θW, the two shaded areas must be equal for heat conservation. This results in a temperature jump of 1°C across the top of the fog layer for this example. Recall from the Water Vapor and Atmospheric Stability chapters that actual temperature within the saturated (fog) layer decreases with height at the moist adiabatic lapse rate (lines of constant θW).

Sample Application(§)

When will fog dissipate if it has an albedo of A = (a) 0.4; (b) 0.6; (c) 0.8 ? Assume daylight duration of D = 12 h. Assume fog forms at to = 3 h after sunset.

Given: FH night = –0.02 K·m s–1, and FH max day = 0.2 K·m s–1. Also plot the cumulative heating.

Find the Answer

Given: (see above) Let t = time after sunset.

Use eq. (6.12), & solve on a spreadsheet:

(a) t = 16.33 h = 4.33 h after sunrise = 10:20 AM

(b) t = 17.9 h = 5.9 h after sunrise = 11:54 AM

(c) Fog never dissipates, because the albedo is so large that too much sunlight is reflected off of the fog, leaving insufficient solar heating to warm the ground and dissipate the fog.

Check: Units OK. Physics OK.

Exposition: Albedo makes a big difference for fog dissipation. There is evidence that albedo depends on the type and number concentration of fog nuclei.