5.2: Bonding and Lattices

- Page ID

- 20129

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Atoms seek to have a full outer shell. For hydrogen and helium, a full outer shell means two electrons. For other elements, it means 8 electrons. Filling the outer shell is accomplished by transferring or sharing electrons with other atoms in chemical bonds. The type of chemical bond is important for the study of minerals because the type of bond will determine many of a mineral’s physical and chemical properties.

Ionic Bonds

Consider the example of halite again, which is made up of sodium (Na) and chlorine (Cl). Na has 11 electrons: two in the first shell, eight in the second, and one in the third (Figure 5.7, top). Na readily gives up the third shell electron so it can have the second shell with 8 electrons as its outermost shell. When it loses the electron, the total charge from the electrons is -10, but the total charge from the protons is +11, so it is left with a +1 charge over all.

Chlorine has 17 electrons: two in the first shell, eight in the second, and seven in the third. Cl readily accepts an eighth electron to fill its third shell, and therefore becomes negatively charged because it has a total charge of -18 from electrons, and a total charge of +17 from protons.

In changing their number of electrons, these atoms become ions—the sodium loses an electron to become a positive ion or cation,[1] and the chlorine gains an electron to become a negative ion or anion (Figure 5.7, bottom). Because negative and positive charges attract, sodium and chlorine ions stick together, creating an ionic bond. In an ionic bond, electrons can be thought of as having transferred from one atom to another.

Cation or Anion?

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Covalent Bonds

Some elements can also form bonds by sharing electrons rather than giving away or receiving them. This will happen when electrons are held especially tightly by their atoms. Chlorine gas (Cl2, Figure 5.9) is formed when chlorine atoms share two outer-shell electrons so that each has a complete outer shell. This is called a covalent bond.

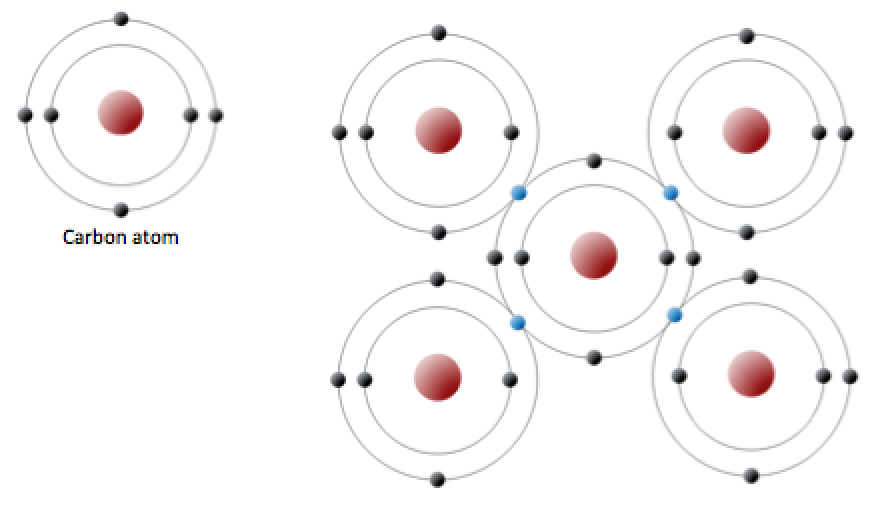

Carbon is another atom that participates in covalent bonding. An uncharged carbon atom has six protons and six electrons. Two of the electrons are in the inner shell and four are in the outer shell (Figure 5.10, left). Carbon would need to gain or lose four electrons to have a filled outer shell, and this would create too great a charge imbalance. Instead, carbon atoms share electrons to create covalent bonds (Figure 5.10, right).

In the mineral diamond (Figure 5.11, left), carbon atoms are linked in a three-dimensional framework, where each carbon atom is bonded to four other carbon atoms. Every bond is a very strong covalent bond.

Other Types of Bonds

Most minerals are characterized by ionic bonds, covalent bonds, or a combination of the two, but there are other types of bonds that are important in minerals.

Van der Waals Forces and Hydrogen Bonds

Consider the mineral graphite (Figure 5.11, right): carbon atoms are linked together in sheets or layers in which each carbon atom is covalently bonded to three others. Graphite-based compounds are strong because of the covalent bonding between carbon atoms within each layer, which is why they’re used in high-end sports equipment such as ultralight racing bicycles. Graphite itself is soft, however, because the layers themselves are held together by relatively weak Van der Waals forces.

Van der Waals forces, like hydrogen bonds, work because molecules can be electrostatically neutral, but still have an end that is slightly more positive and an end that is slightly more negative. In water molecules (Figure 5.12, left), the bent shape puts the hydrogen atoms on one side of the molecule, and the oxygen atom, with more electrons, on the other. The charge is distributed asymmetrically across the water molecule. Contrast this with the straight carbon dioxide molecule (Figure 5.12, right). The slightly more negative oxygen atoms on the ends are distributed symmetrically on either side of the carbon atom.

Metallic Bonds

Metallic bonding occurs in metallic elements because they have outer electrons that are relatively loosely held. (The metals are highlighted on the periodic table in Appendix 1.) When bonds between such atoms are formed, the dissociated electrons can move freely from one atom to another. This feature accounts for two very important properties of metals: their electrical conductivity and their malleability (they can be deformed and shaped).

Chemical Bond Types

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

- You can remember that a cation is positive by remembering that a cat has paws (paws sounds like "pos" in "positive"). You could also think of the "t" in "cation" as a plus sign. ↵