5.3: Mineral Groups

- Page ID

- 20130

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Minerals are organized according to the anion or anion group (a group of atoms with a net negative charge, e.g., SO42–) they contain, because the anion or anion group has the biggest effect on the properties of the mineral. Silicates, with the anion group SiO44-, are by far the most abundant group in the crust and mantle. (They will be discussed in Section 5.4). The different mineral groups along with some examples of minerals in each group are summarized below.

Oxide Minerals: O2- Anion

Oxide minerals (Figure 5.14) have oxygen (O2–) as their anion. They don’t include anion groups with other elements, such as the carbonate (CO32–), sulphate (SO42–), and silicate (SiO44–) anion groups. The iron oxides hematite and magnetite are two examples that are important ores of iron (minerals that are mined for their iron content). Corundum is an abrasive, but can also be a gemstone in its ruby and sapphire varieties. If the oxygen is also combined with hydrogen to form the hydroxyl anion (OH–), the mineral is known as a hydroxide. Some important hydroxides are limonite and bauxite, which are ores of iron and aluminum, respectively.

Sulphide Minerals: S2- Anion

Sulphide minerals (Figure 5.15) include galena, sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and molybdenite, which are the most important ores of lead, zinc, copper, and molybdenum, respectively. Some other sulphide minerals are pyrite, bornite, stibnite, and arsenopyrite. Sulphide minerals tend to have a metallic sheen.

Sulphate Minerals: SO42- Anion Group

Many sulphate minerals form when sulphate-bearing water evaporates. A deposit of sulphate minerals may indicate that a lake or sea has dried up at that location. Sulphates with calcium include anhydrite, and gypsum (Figure 5.16). Sulphates with barium and strontium are barite and celestite, respectively. In all of these minerals, the cation has a +2 charge, which balances the –2 charge on the sulphate ion.

Halide Minerals: Anions from the Halogen Group

The anions in halides are the halogen elements including chlorine, fluorine, and bromine. Examples of halide minerals are cryolite, fluorite, and halite (Figure 5.17). Halide minerals are made of ionic bonds. Like the sulphates, some halides also form when mineral-rich water evaporates.

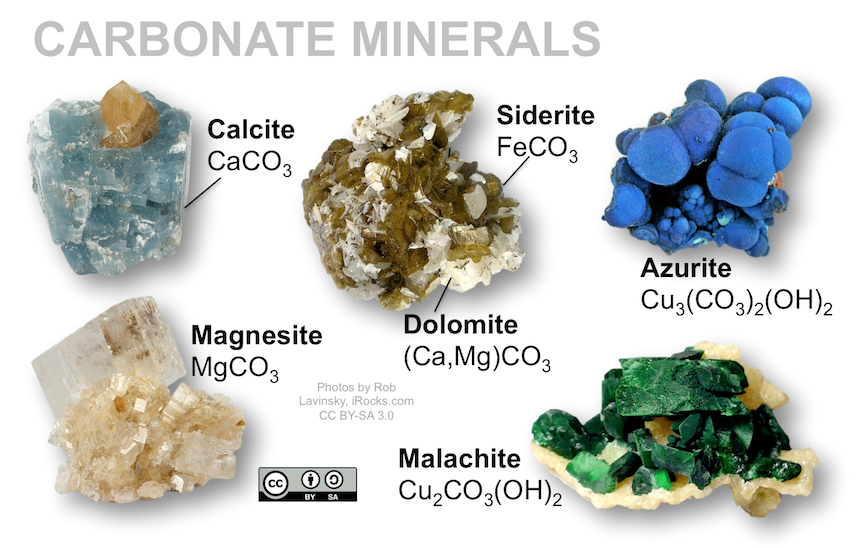

Carbonate Minerals: CO32- Anion Group

The carbonate anion group combines with +2 cations to form minerals such as calcite, magnesite, dolomite, and siderite (Figure 5.18). The copper minerals malachite and azurite are also carbonates. The carbonate mineral calcite is the main component of rocks formed in ancient seas by organisms such as corals and algae.

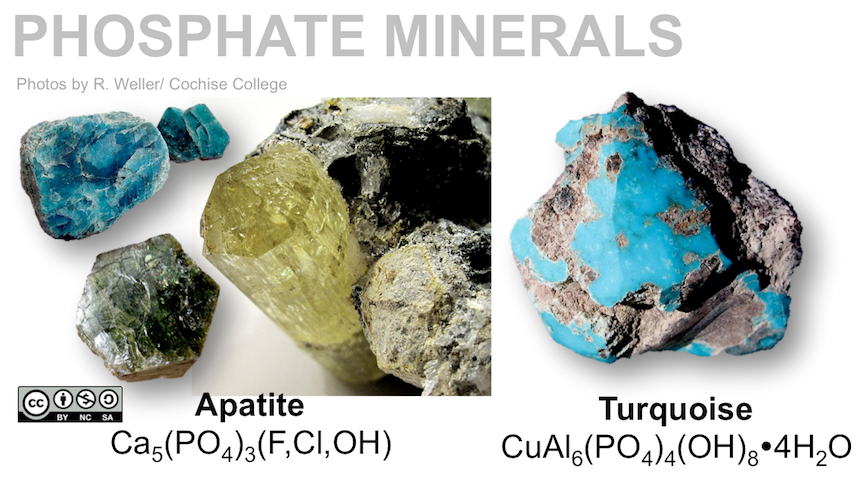

Phosphate Minerals: PO43- Anion

The apatite group of phosphate minerals (Figure 5.19, left) includes hydroxyapatite, which makes up the enamel of your teeth. Turquoise is also a phosphate mineral (Figure 5.19, right).

Silicates (SiO44–)

The silicate minerals include the elements silicon and oxygen in varying proportions . These are discussed at length in Section 5.4.

Native Element Minerals

These are minerals made of a single element, such as gold, copper, silver, or sulphur (Figure 5.20).

Beginner Practice with Anionic Groups

Minerals are grouped according to the anion part of the mineral formula, and mineral formulas are always written with the anion part last. For example, in pyrite (FeS2), Fe2+ is the cation and S– is the anion. This helps us to know that it’s a sulphide, but it isn’t always that obvious…

Hematite (Fe2O3) is an oxide; that’s easy, but anhydrite (CaSO4) is a sulphate because SO42– is the anion, not O. Similarly, calcite (CaCO3) is a carbonate, and olivine (Mg2SiO4) is a silicate.

Minerals with only one element (such as S) are native minerals, while those with an anion from the halogen column of the periodic table (Cl, F, Br, etc.) are halides.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Anionic Groups: Level Up!

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)