12.1.8: The Discovery of X-rays and Diffraction

- Page ID

- 18373

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Scientists studied minerals for hundreds of years before the discovery of X-rays. By the late nineteenth century, mineralogists knew that crystals had ordered and repetitive crystal structures. They hypothesized about atomic arrangements and the nature of crystal structures, but they lacked direct evidence. Some ideas about crystal structure were generally accepted, while others were poorly understood and hotly debated. Without a way to test hypotheses, development of an understanding of atomic arrangement and of bonding in crystals was stalled.

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1895 allowed mineralogists to proceed with their studies and eventually led to a greater understanding of crystal structures. Mineralogists quickly discarded many hypotheses disproved by X-ray studies; just as quickly, they developed and tested new ones. In less than two decades, scientists developed a firm theoretical basis for understanding how atoms are arranged in minerals.

Today we accept without question the idea that atoms bond together in regular arrangements to make crystals. We draw pictures, make enlarged models, and study the details of crystal structures of thousands of minerals. All this knowledge would have been unobtainable if Röntgen and his coworkers had not recognized the importance of some curious phenomena they observed while studying cathode ray tubes (early versions of television tubes) in 1895.

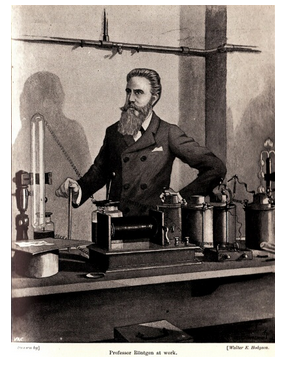

Röntgen taught and studied physics at the University of Würzburg in Germany. He was studying the relationship between matter and force as charged particles flowed from a heated filament in an evacuated glass tube. By chance, he observed that a nearby piece of barium platinocyanide fluoresced when he turned on the tube. Röntgen deduced that electrons interacting with the walls of the tube produced a high-energy form of radiation, and he showed that the radiation could penetrate paper and even thin metals. Because the radiation seemed to behave differently from light, he thought it a completely different phenomenon, calling it X-radiation. Various physicists searched for an understanding of the nature of X-radiation. X-rays became inextricably involved with mineralogy when Max von Laue successfully used crystals as a tool in this search.

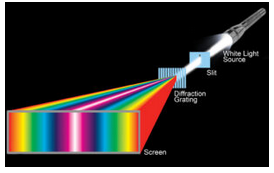

The diffraction of light was well understood at the time. Physicists routinely measured the wavelengths of colored light using finely spaced diffraction gratings. The gratings consist of many parallel slits (or sometimes grooves), typically spaced between 0.0002 and 0.03 mm apart. Light passing through a grating is dispersed – which means it is separated into different colors that go in different directions (Figure 12.3).

In 1911, von Laue, a physics professor in Münich, determined that lines in diffraction gratings were not spaced closely enough to diffract X-rays. This partly explained Röntgen’s confusion about the relationship between light and X-rays. Von Laue hypothesized that the distance between atoms in crystals, being much less than the distance between lines in diffraction gratings, could lead to X-ray diffraction. And, so he ushered in the field of X-ray crystallography.

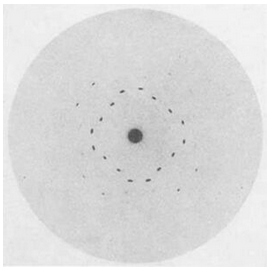

In 1912, Walter Friedrich and Paul Knipping confirmed von Laue’s ideas when they caused X-rays to pass through crystals of copper sulfate (CuSO4) and sphalerite (ZnS) and recorded diffraction patterns on film (Figure 12.4). Their studies showed that X-rays are electromagnetic waves similar to light, but with much shorter wavelengths. They also confirmed that crystals must have a regular crystal structure.

The impact of the work by von Laue and his students was immense. Paul Debye and Paul Scherrer soon improved X-ray techniques. They showed that all crystals have a lattice and that lattices vary in their symmetry. In 1913 William H. Bragg and his son William L. Bragg determined the arrangement of atoms in sphalerite, ZnS, using data obtained with X-ray studies. For the first time, mineralogists knew the actual locations of atoms within a crystal. Similar studies on other crystalline compounds soon followed as Linus Pauling and other scientists realized the power of X-ray diffraction.

Early X-ray studies were tedious. Scientists could spend an entire career determining the atomic arrangement in only a few minerals. Today, with sophisticated equipment and high-speed computers, crystal structure analyses are often routine and can be completed in less than a day. It is important to remember, however, that without the pioneering work of Röntgen, von Laue, the Braggs, Pauling, and others, we would have no detailed knowledge of how atoms are arranged in minerals. In 1901 Röntgen received the first Nobel Prize for Physics; von Laue received the same prize in 1914, and both Braggs were the recipients in 1915.