9.1.5: Worldwide Distribution

- Page ID

- 18486

Geological processes that concentrate minerals are not unusual. But, the processes that create economically productive ore deposits are rare. If they were not, market prices would fall, decreasing profits and putting some mines out of business. Thus, the largest and most easily produced mines control market prices. Old mines shut down and new mines open up when new discoveries are made. Today, however, new discoveries are generally smaller than in the past because the largest deposits, which are more easily found than smaller deposits, have already been developed.

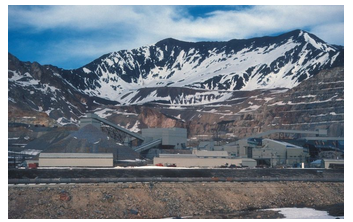

Because the geology of Earth varies, the distribution of ore deposits around the globe is uneven, and the minerals industry flourishes in some places and not in others. Some regions of the world contain most of the supply of certain commodities; this can affect international politics. For example, the United States controls about half the world’s molybdenum. Figure 9.18 shows the Climax Mine in Colorado. This mine has historically been the largest producer of molybdenum in the world. Production started in 1915, but the mine temporarily shut down between 1995 and 2012 due to low molybdenum prices. Nonetheless, the US has sufficient supply of molybdenum. Unfortunately, many other important minerals are not produced in the United States. We call these minerals critical minerals, or strategic minerals (See Box 9-2). Additionally, we import many mineral commodities, that we might produce ourselves, because it would cost too much to mine them in our own country; tungsten is a good example.

Australia produces about a quarter of the world’s aluminum, and Zaire half the cobalt. China accounts for 95% of all rare earth production, although significant reserves are found in other countries. South Africa, a country rich in mineral commodities, controls 90% of the world’s platinum, half the world’s gold, and 75% of the chromium. Much of the world’s tin comes from Bolivia and Brazil.

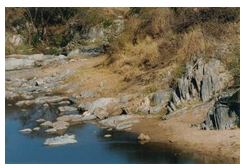

South Africa is, arguably, the number one mining country in the world. Most South African ore deposits are associated with regions called Precambrian greenstone belts, ancient volcanic terranes. Similar greenstone belts in Canada account for many of North America’s metallic ore deposits. Figures 9.19, 9.20, and 9.21, above show rocks of greenstone belts in Africa, Canada, and Tanzania. Various other types of geological terranes are associated with ore deposits, too. Most economical metal and semimetal deposits are found near margins of continents, or the former margins of continents, where mountain building and igneous activity have occurred. Still, other types of deposits are found in continental interiors.

Strategic Minerals and Metals

We use many different minerals and metals to maintain our lifestyles and provide military security. Some of these commodities are not found or produced in the United States in sufficient quantities to meet demand. Consequently, we must import them from other nations. And sometimes supplies are problematic. During the Cold War, for example, the former Soviet Union and its allies stopped exporting minerals commodities to the Untied States. At various times since then the United States has stopped importations from Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Libya, and North Korea. So, sources of strategic metals are controlled by politics as well as geology.

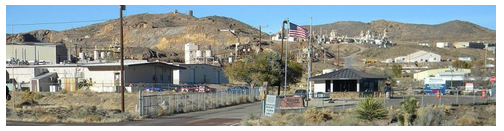

Consider the push to expand the use of electric vehicles (EVs). The Netherlands, United Kingdom, France and some other countries have announced ambitious plans to completely eliminate gasoline and diesel vehicles. China is moving in that direction as well. But EVs need batteries and, although battery technology continues to evolve, lithium and cobalt are key components. Only eight countries produce lithium, and most of it comes from only three countries. Cobalt supplies are even more limited. The Democratic Republic of the Congo produces just about all of the world’s cobalt. Batteries also require rare earth elements (REEs), and China controls the market – accounting for 95% of total REE production. The last functioning rare earth mine in North America closed for financial reasons in 2015 (Figure 9.22, below). Thus, the United States is heavily reliant on just a few countries if we are to expand electric vehicle technology and keep up with the rest of the world.

Further complicating the picture is that the United States is both an importer and an exporter of some key metals and minerals. Today, the US relies entirely on imports for the following important element and mineral commodities:

arsenic, asbestos, cesium, fluorite, gallium, graphite, muscovite, niobium, rare earth elements, rubidium, scandium, strontium, tantalum, thorium

The United States is partially reliant on imports to meet needs for these element and mineral commodities:

aluminum, antimony, barite, beryllium, bismuth, chromium, cobalt, copper, diamonds, germanium, hafnium, indium, lithium, magnesium, manganese, nickel, platinum group metals, potash, rhenium, silver, tellurium, tin, tungsten, uranium, vanadium, zirconium

The United States is a net exporter of:

boron, clays, diatomite, gold, helium, iron, kyanite, molybdenum, selenium, titanium, trona, wollastonite, zeolites