9.1.2: The History of Mining

- Page ID

- 18483

Mining is nothing new. People have practiced mining and quarrying since ancient times. The first mineral known to be mined was flint, a fine-grained variety of quartz used to make weapons. Early peoples mined other things, such as ochre, for use as pigment in art and religious ceremonies.

Archaeologists and anthropologists define major periods of human civilization based on resources used. There is a great deal of overlap and different regions moved from one period to another at different times. The late Stone Age, also called the Neolithic Age, was followed by the Chalcolithic Age from 4,500 to 3,500 BCE (Before Common Era). During the Chalcolithic Age, humans began using copper (the name chalcolithic is derived from the Greek word khalkos for copper) for both decorative and utilitarian purposes. One of the largest collections of chalcolithic artifacts was discovered in a cave in Israel’s Judean Desert in 1961 (Figure 9.3). Because copper could be found as malleable pure copper nuggets, people could shape it with available stone tools – a property that no other common minerals possessed. A rise in consumption of copper coincided with the development of a socioeconomic hierarchy, and the wealthy citizens possessed more copper than the proletariat.

Figure 9.4 shows artifacts from the Bronze Age, the age that followed the Chalcolithic Age and lasted from about 4,200 to 1,000 BCE. Use of bronze first developed in the Mesopotamian civilization of Sumeria and became common in other places later. This was a period characterized by a rapid rise of resource consumption and increasing diversification of products made by metalworking. Perhaps the most significant advancement in metal use was the discovery of how to make bronze, an alloy created by melting and combining the metals copper and tin. Although tin melts at a relatively low temperature (232 °C), copper melts at 1,983 °C, a temperature too great to be easily achieved at the time. However, clever metal workers discovered that a mix of one part tin and three parts copper melts at 1,675 °C, which was low enough to make bronze manufacturing possible in many places.

The map in Figure 9.5 shows the location of Bronze Age mines that provided metals used throughout much of the Middle East. Most of the copper came from the Troodos Mountains of Cyprus, where copper could be found in loose sediments at Earth’s surface. Even today, a great deal of copper mining takes place in Cyprus, although most operations have moved underground. Figure 9.6 shows the Skiriotissa Mine, which was the site of Bronze Age mining and is an active mine today. Although some copper and other metals came from mines on Cyprus and on the Asian mainland, tin deposits were generally small or hard to produce. The scarcity of tin in the Middle East and other areas of the Mediterranean region, meant that tin ores came from as far away as the British Isles, which the Greeks named the Cassiterides, that translates to Tin Islands.

A key property that allowed humans to work with bronze is that, after pouring the molten bronze into stone molds and allowing the liquid to cool to a solid, the copper-tin alloy could be formed and shaped using hammers at room temperature, a process called cold working. And, because bronze is much stronger than copper, people could make many improved products, including knives, shields and swords, and tools that led to more productive agriculture.

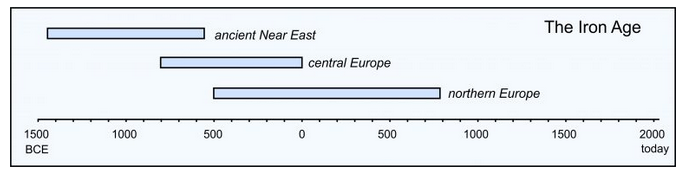

The Iron Age followed the Bronze Age beginning around 1500 BCE, when the Hittite society of ancient Anatolia (modern day Turkey) discovered how to process iron. Their technological breakthrough was to add a small amount of charcoal (carbon) to rocks that contained iron. Pure iron melts at 1,538 °C, but adding carbon results in a carbon-iron mixture that melts at 1,170 °C. The Hittites also figured out that iron-carbon alloys could not be cold-worked like bronze but had to be hammered and shaped while hot. Thus, they invented the art of modern blacksmithing. The iron and alloys produced, once cooled, were much stronger and harder than bronze was. After the time of the Hittites, it took another 500 to 1,000 years for the iron age to reach central and northern Europe (Figure 9.7).

The source of iron used by the Hittites was metallic meteorites. Meteorites also contained a small amount of nickel that improved metal properties. Because iron-rich meteorites were not in abundance, the Hittites carefully guarded their invention of iron metal working for several centuries. During those centuries, the Hittites exercised military superiority over much of the Middle East and Egypt, where the weaker bronze was used in battle. However, by 1200 BCE, iron metal working technology had spread across the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and to Asia; people discovered new sources of iron; and the Hittite empire disappeared.

Egyptians mined native metals, including gold, silver, and copper, from stream beds as early as 3700 to 3000 BCE. Around 2600 BCE they began to quarry stone to build the Great Pyramids. By the Middle Ages, mining was common in Europe. Georgius Agricola (Figure 9.8), a German physician, wrote the first widely read book about mining, De re metallica, published in 1556. Agricola’s work is said by some to represent the beginning of the science of mineralogy.

Mineral resources literally put places on the map of the ancient world. If a region contained abundant amounts of copper, silver, tin, or gold, and later iron, it soon became populated and prosperous. Civilizations established trade routes and developed commercial systems, shipping commodities over increasingly longer distances. If resource supplies became depleted in one location, people sought new sources. Thus, exploration was needed to sustain production and consumption of valuable resources. These same dynamics operate today: when new mineral deposits are discovered, new communities and industries may appear. When old deposits become depleted, communities and industries wane. And, always, mining companies are exploring to find new sources of economically viable minerals.

Copper, tin, iron, and nickel were all important during the early ages of humans, and they are equally important today. Those same metals – and many others – are key parts of a seemingly infinite number of products. For example, Figure 9.9 (below) shows the many minerals that provide elements that are in a smart phone. Copper makes up about 10% of the weight of a smartphone, and that copper is the key to moving around the electricity that powers the phone. Tin is used to make the liquid crystal display (LCD) screen and to solder electrical connections that transmit digital information. Iron is combined with the metals neodymium and boron to make magnets that are part of the microphone and speaker. And those are not the only elements in a smartphone; there are about 75 elements in all. Without any one of these elements, smartphones would not exist as they do. Nearly everything that we manufacture contains mineral resources, and the sources for these resources are mineral deposits.