12.2: The Story of Basins Past, Present, and Future

- Page ID

- 22666

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Plates move and collide, mountains rise, sea level ebbs and flows. All the while, chemical and physical weathering processes, buoyed by important interactions between the Earth’s spheres, break rock down in place. After it breaks down, erosional forces powered by gravity and aided by wind, water, and ice provide the energy and work necessary to move weathered materials downhill, downstream, into a new place of rest. The story of these weathered sediments, large and small, has great variety. Numerous variables determine the outcome for these sediments. Latitude, the parent rock that weathered, the climate and degree of physical and chemical weathering, life forms that interacted with the grains, and so many more ultimately determine the story eventually told by the layers of sediment. As these layers accumulate, so does the tableau of stories they tell.

Strata

Sedimentary rocks come in strata, or layers, much like a nice birthday cake or pages in a storybook, and stratigraphy is the study of the record of these layers. These rocks are formed from sediments originally deposited in a basin. A basin is an area of depressed elevation generally surrounded by land at higher elevations. Basins can be on dry land or be filled with freshwater or saltwater. Over time, the land surrounding a basin erodes and the resulting sediment begins to fill the basin. From the point of origin in the highlands to the point of deposition in the basin, a great deal can happen to this sediment. Weathering, in various physical and chemical forms, takes its toll. By the time of their final moment of deposition, these sediments record a memory of their former existence as rocks, of their transport journey, and of processes that occur in the basin. Much of this sediment is solid and arrives as particles. Some of it arrives in aqueous solution, becoming the salts we experience in the seas around us. Some of it forms in the bodies of organisms, such as carbon-rich plant tissues or the skeletal remains of animals.

Depending upon the distance particles travel, some will remain the size of massive boulders and some will be reduced to the size of tiny flakes of clay. The range of grain sizes, or sorting, is the result of weathering and subsequent changes in energy as the particles move downslope. Some are well-rounded, others still retain their rough edges. Some sediment, found far from its source, will be composed primarily of quartz, with less stable minerals having rotted away. Other sedimentary deposits will still contain unweathered minerals like micas and feldspars. Once deposited, sediment and rock will begin to undergo physical and chemical processes associated with the local environment. Soil formation will begin on land. In marine settings, chemical processes associated with water chemistry and biogenic materials will occur, adding onto the earlier story of transport. These layers of sediment, accumulating over time, are the subject of stratigraphy.

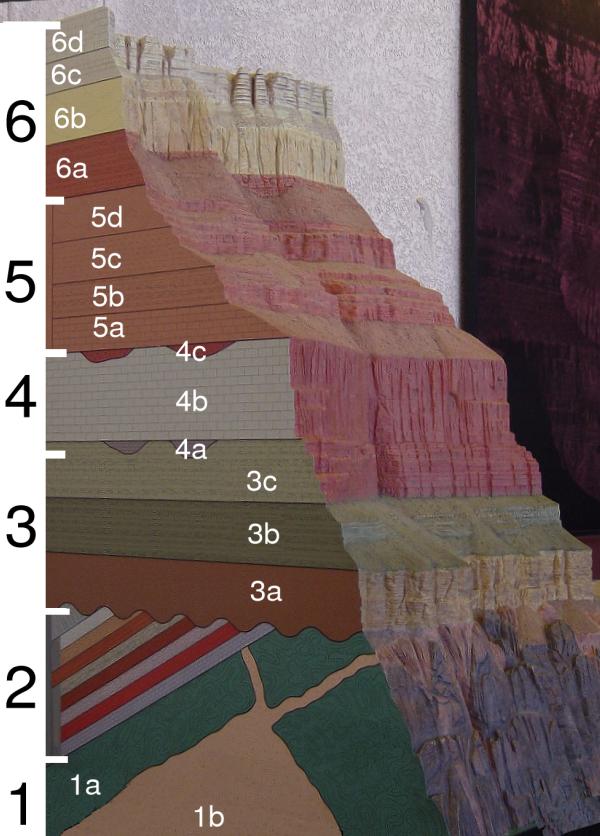

The journey a sediment grain takes ultimately ends with deposition in a basin. Throughout that journey, sediments will take up residence for a time, waiting for a sufficiently energetic event to move them further along toward this end. The collective experience of sedimentation along these myriad pathways creates situations, as illustrated above, where different depositional environments are created. Geologists refer to the unique sedimentary characteristics of these varying environments with the term “facies“. A sedimentary facies is defined as the body of characteristics of a sediment, or rock, that are indicative of the environment of deposition at the time. Real-time facies migrate, or change, at a location as conditions change. All of the environments in the figure above are dynamic in nature. We can also assume, using uniformitarianism, that similar environments have existed in the past, producing rocks in the geologic record that record similar characteristics we see in their modern counterparts. As sediments deposit and facies migrate, strata are generated. Geologists call such strata, beds. As beds representing similar environments accumulate and lithify, they will come down to us as mappable units called formations.

All of this action ultimately occurs in sedimentary basins.

Basins

Basins can be thought of as a library filled with books, which are the layers of rock that accumulate. These layers tell the story of global geologic changes, regional changes, and changes within the basin itself. There is great variety among sediments and other materials deposited in basins and in the layers, or strata, that they create. This variety and layering provides the equivalent of text on the pages of a novel or even in this textbook. Individual pages are the strata, or beds, and their characteristic portion of the story on that page are the facies. These pages are laid down horizontally, building up vertically over time, reflecting the order in which they occurred (superposition). Eventually, these pages (beds) accumulate into books (formations). Processes that occur after deposition, such as lithification, deformation, and further weathering and erosion can then make changes to this record that are akin to the deterioration seen in ancient Egyptian papyrus, or in a book whose pages and cover have been subject to the ravages of the elements. Strata can be torn (faulting), wrinkled (folding), or younger material may be injected (igneous intrusions). Depending on the context, these modifications may provide some confusion or clarification to the overall story. Over time, some of the material that makes up the strata and rock of this “book” can be lost or altered (erosion, metamorphism, secondary chemical alteration, etc.). Sometimes, even entire pages, or beds, are removed. Entire books, or formations, can be truncated, leaving gaps in the storyline (unconformities). Stratigraphers grapple with a record that was incomplete to begin with, and is further reduced over geologic time. Still, the remaining story these layers of sediment have to tell is powerful and important. It is of critical value in providing a more complete understanding of the history of our planet, including your own home landscape. Geologists who study this record are called stratigraphers. They are the historians within the geosciences.

Consider the office bookcase below as a stratigraphic metaphor:

Facies – The words, notations, etc. on an individual page of a book;

Beds = Pages within periodicals or books;

Formations = Books full of pages, come complete, some perhaps incomplete;

Groups of Formations = Shelves of books with similar topics (assuming they are organized as in a library!);

Bookcase = Stratigraphic record of the entire basin.

The limitation of this metaphor is that most of the “stratigraphy” you see here is vertical, implying a great deal of geologic alteration. Putting that aside and remembering the “Principle of Original Horizontality”, we know that if these were rocks, they would be stacked differently.

The gigapan below depicts the Hampshire Formation. It was taken along Corridor H (US 48) in West Virginia. The image depicts a single formation. If you observe this formation, akin to a book, you may first see the varying color. These are beds. Some of these beds, or pages, could be broken down further into smaller beds. Ultimately, these beds are all related because they were deposited in similar depositional environments, as illustrated by their facies.

Layers of sediment are not static recipients of the story only. They are also participants. As we will learn in the next section, they are recording their story and being acted upon by outside forces such as tectonic change, sea level change, and lithification. But, they are also having their own impact on tectonics and sea level. Layers of sediment also play an important role in the record of geologic history that is important to understand also. As these layers accumulate in basins, they record the history of an area. Stratigraphy is the study of that history.