5.4: Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

- Page ID

- 22627

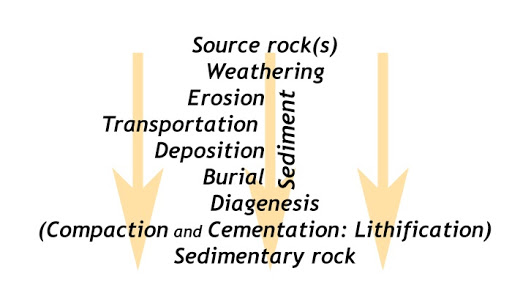

Sedimentary rock formation is a cycle unto itself and is discussed in more detail elsewhere in this text. The flow through that cycle appears below.

The cycle begins with the exposure of pre-existing rock to the “agents” of weathering and erosion. Weathering involves exposure of pre-existing rock to Earth’s surface weather conditions. These “agents” include wind, water and ice — plus gravity. Erosion is the removal of weathered rock material from its original location. The effects of weathering on pre-existing rock can be both physical and chemical.

Physical Weathering

Physical weathering is simply the process of physical disintegration: the breaking of solid rock into smaller pieces. The “agents” assist in this process which results in the exposure of an ever increasing number of surfaces to additional weathering.

Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering produces changes in the chemistry of minerals in the pre-existing rock. These changes may result in new mineral formation through the addition or subtraction of elements from the original mineral structure or, in the further disintegration of the pre-existing minerals by chemical decomposition. The dominant agent involved in both physical and chemical weathering is water. Water acts as an agent of change, both introducing elements that can interfere with the chemistry of the exposed minerals and also acting as a flux, physically removing weathered rock material and ions lost through decomposition.

Weathering produces particles of sediment (of various sizes) plus ions in water. The sediment is transported to some setting where it gets deposited. This depositional location may be very close to the origin of the sediment (such as a rock fall off a cliff face) or many hundreds (or even several thousand) of kilometers away (for example the beach along the continental shoreline). Following deposition, the sediment is buried, compacted, and cemented together to form solid rock. We call these processes “diagenesis,” and collectively they serve to lithify the sediment into a rock.

The ions in solution (weathered chemical elements) can be:

- used in cementing particles sediment.

- extracted from the water to support life, both biochemical processes (in plants or animals) and in the formation of skeletal material, such as shells.

- precipitated from the water through supersaturation triggered by evaporation or by changing physical conditions of the surrounding water.

The importance of these processes to Historical Geology are discussed in much more detail elsewhere in this text. The simple classification of sedimentary rock is presented below.