4.3.1: The Structure of the Earth

- Page ID

- 15642

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Since we humans live on the very surface of the Earth, we do not tend to think too much about what is beneath the basements of our homes and workplaces. The Earth is nearly 8000 miles in diameter (almost 13,000 km), the distance you would travel if you went straight through the earth to the exact opposite point on the globe. If you traveled through the earth this way, you would pass through many different layers, the temperature would get as hot as the surface of the sun, and you would see things no human eyes have ever seen before!

Compositional Layers

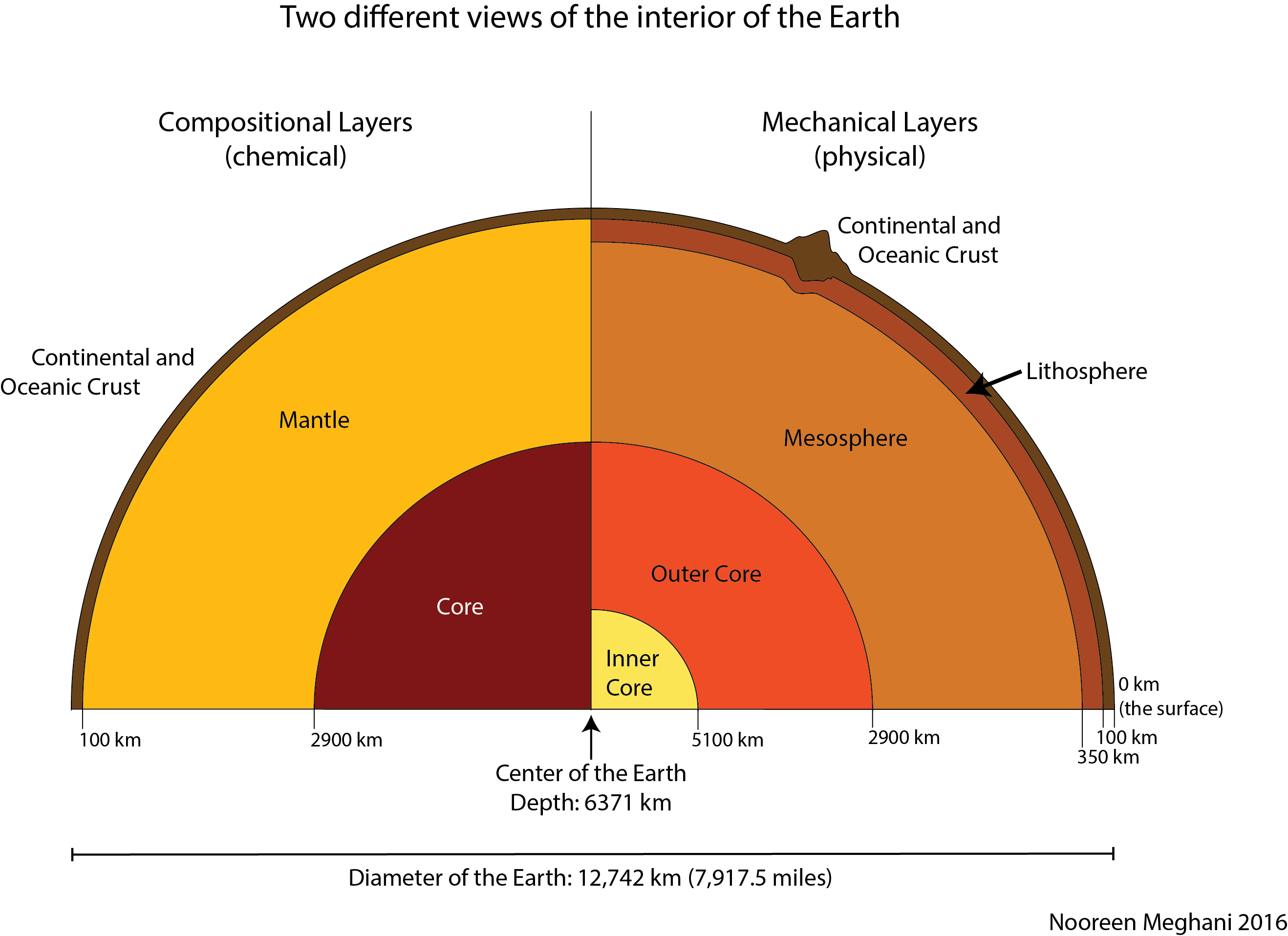

The Earth has different compositional and mechanical layers. Compositional layers are determined by their components, while mechanical layers are determined by their physical properties.

| Layer | Definition | Depth |

|---|---|---|

| Crust | The outermost solid layer of a rocky planet or natural satellite. Chemically distinct from the underlying mantle. | 0-100km silicates |

| Mantle | A layer of the Earth (or any planet large enough to support internal stratification) between the crust and the outer core. It is chemically distinct from the crust and the outer core. The mantle is not liquid. It is, however, ductile, or plastic, which means that on very long time scales and under pressure it can flow. The mantle is mainly composed of aluminum and silicates. | 100-2900km iron and magnesium silicates |

| Core | The innermost layers of the Earth. The Earth has an outer core (liquid) and an inner core (solid). They are not chemically distinct from each other, but they are chemically distinct from the mantle. The core is mainly composed of nickel and iron. | 2900-6370km metals |

Mechanical Layers

The mechanical layers of the Earth a differentiated by their strength or rigidity. These layers are not the same as the compositional layers of the Earth, such as the crust, mantle, and core, though sometimes the boundaries fall in the same places.

| Layer | Definition | Depth |

|---|---|---|

| Lithosphere | The outermost and most rigid mechanical layer of the Earth. The lithosphere includes the crust and the top of the mantle. The average thickness is ~70km, but ranges widely: It can be very thin, only a few km thick under oceanic crust or mid-ocean ridges, or very thick, 150+ km under continental crust, particularly mountain belts. | 0-100 km |

| Asthenosphere | The asthenosphere is underneath the lithosphere. It is about 100km thick, and is a region of the mantle that flows relatively easily. Reminder: it is not liquid. | 100-350 km Soft plastic *note: The mantle is not liquid! |

| Mesosphere | The mesosphere is beneath the asthenosphere. It encompasses the lower mantle, where material still flows but at a much slower rate than the asthenosphere. | 350-2900km stiff plastic |

| Outer Core | A layer of liquid iron and nickel (and other elements) beneath the mesosphere. This is the only layer of the Earth that is a true liquid, and the core-mantle boundary is the only boundary of Earth’s layers that is both mechanical and compositional. Flow of the liquid outer core is responsible for Earth’s magnetic field. | 5100-6370 km solid |

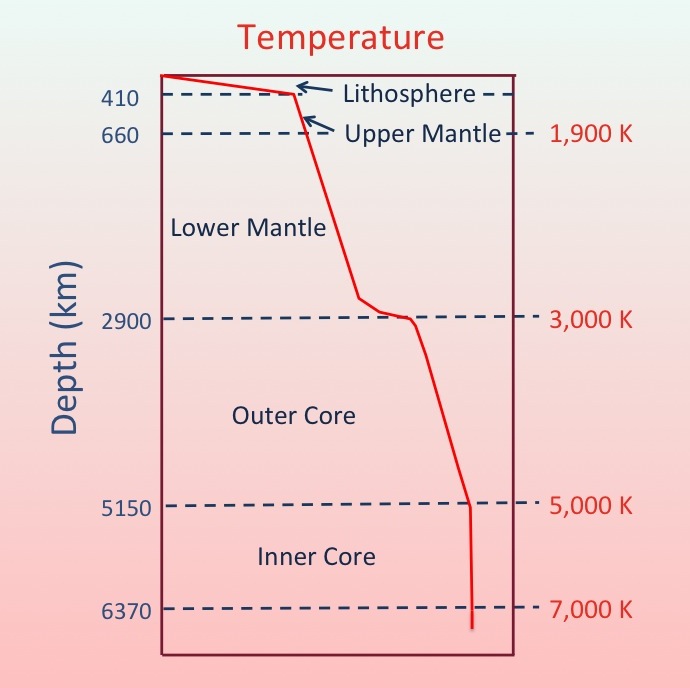

You may be wondering how it is that layers of the Earth can be liquid, or ‘plastic’. When we describe these properties of the layers of the Earth, it is important to remember that the Earth moves and changes on very long time scales. Something that appears to be solid on a short time scale can, in fact, be liquid. Glass is an example of an ‘amorphous solid’ – a material that is neither liquid nor solid. Over long periods of time glass can flow, forming (for example) windowpanes with thick bottoms and thin tops in old buildings. The mantle is like this. When it is under stress for long periods of time, it can flow. Due to the incredibly high temperatures and pressures near the center of the Earth, the outer core is liquid iron and nickel, while the inner core is solid. The motion of the liquid outer core is what gives Earth its magnetic field. Take a look at how temperature in the earth change with depth.

The image above of the layers of the Earth is very simplified. Much in the way that we can use a stick figure to represent a person but lacks all of the detail, a wealth of information is missing in order to highlight the general distinctions between the layers of the Earth. It’s important to remember that these systems are incredibly complex. If you’re interested in learning more about the different layers of the Earth and how we know where they are, check out the United States Geological Survey website!