13.2: Drainage Basins

- Page ID

- 7849

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

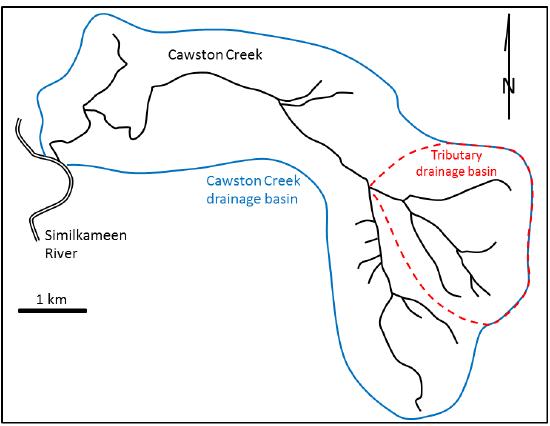

A stream is a body of flowing surface water of any size, ranging from a tiny trickle to a mighty river. The area from which the water flows to form a stream is known as its drainage basin. All of the precipitation (rain or snow) that falls within a drainage basin eventually flows into its stream, unless some of that water is able to cross into an adjacent drainage basin via groundwater flow. An example of a drainage basin is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

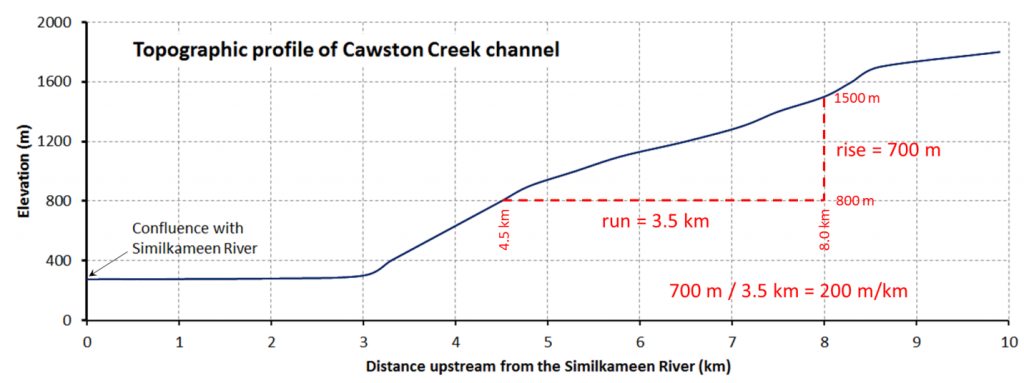

Cawston Creek is a typical small drainage basin (approximately 25 square kilometers) within a very steep glaciated valley. As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), the upper and middle parts of the creek have steep gradients (averaging about 200 meters per kilometre but ranging from 100 to 350 meters per kilometre), and the lower part, within the valley of the Similkameen River, is relatively flat (less than 5 meters per kilometre). The shape of the valley has been controlled first by tectonic uplift (related to plate convergence), then by pre-glacial stream erosion and mass wasting, then by several episodes of glacial erosion, and finally by post-glacial stream erosion. The lowest elevation of Cawston Creek (275 meters at the Similkameen River) is its base level. Cawston Creek cannot erode below that level unless the Similkameen River erodes deeper into its flood plain (the area that is inundated during a flood).

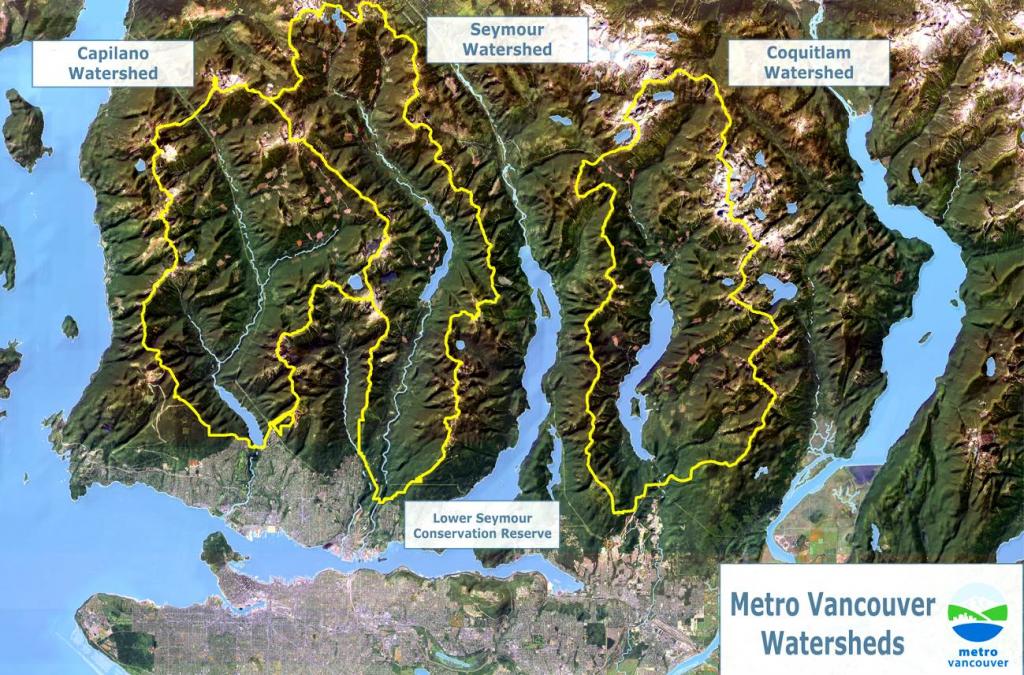

Metro Vancouver’s water supply comes from three large drainage basins on the north shore of Burrard Inlet, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). This map illustrates the concept of a drainage basin divide. The boundary between two drainage basins is the height of land between them. A drop of water falling on the boundary between the Capilano and Seymour drainage basins (a.k.a., watersheds), for example, could flow into either one of them.

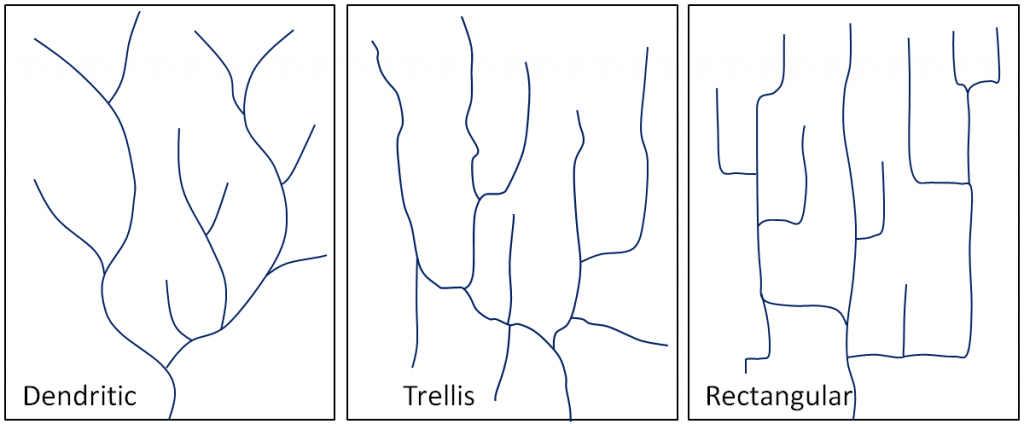

The pattern of tributaries within a drainage basin depends largely on the type of rock beneath, and on structures within that rock (folds, fractures, faults, etc.). The three main types of drainage patterns are illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). Dendritic patterns, which are by far the most common, develop in areas where the rock (or unconsolidated material) beneath the stream has no particular fabric or structure and can be eroded equally easily in all directions. Examples would be granite, gneiss, volcanic rock, and sedimentary rock that has not been folded. Most areas of British Columbia have dendritic patterns, as do most areas of the prairies and the Canadian Shield. Trellis drainage patterns typically develop where sedimentary rocks have been folded or tilted and then eroded to varying degrees depending on their strength. The Rocky Mountains of B.C. and Alberta are a good example of this, and many of the drainage systems within the Rockies have trellis patterns. Rectangular patterns develop in areas that have very little topography and a system of bedding planes, fractures, or faults that form a rectangular network. Rectangular drainage patterns are rare in Canada.

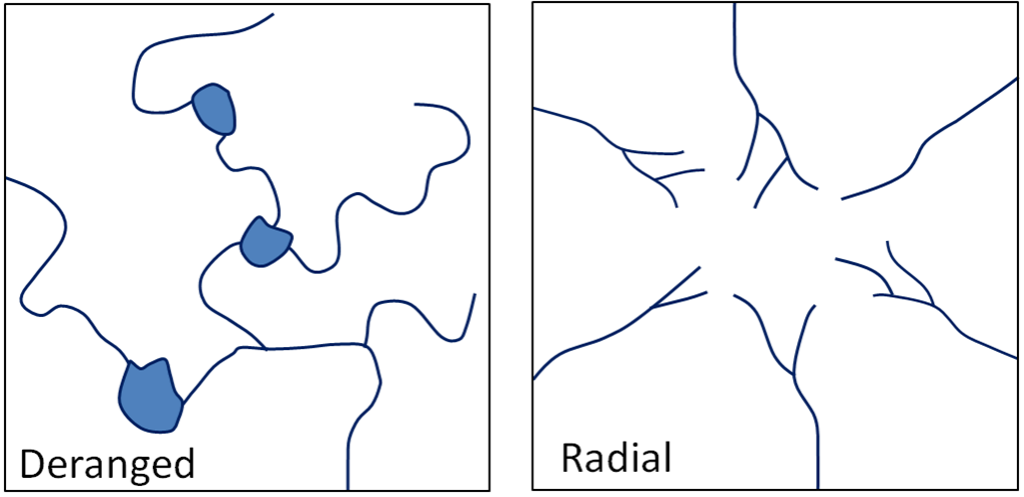

In many parts of Canada, especially relatively flat areas with thick glacial sediments, and throughout much of Canadian Shield in eastern and central Canada, drainage patterns are chaotic, or what is known as deranged (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), left). Lakes and wetlands are common in this type of environment.

A fourth type of drainage pattern, which is not specific to a drainage basin, is known as radial (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), right). Radial patterns form around isolated mountains (such as volcanoes) or hills, and the individual streams typically have dendritic drainage patterns.

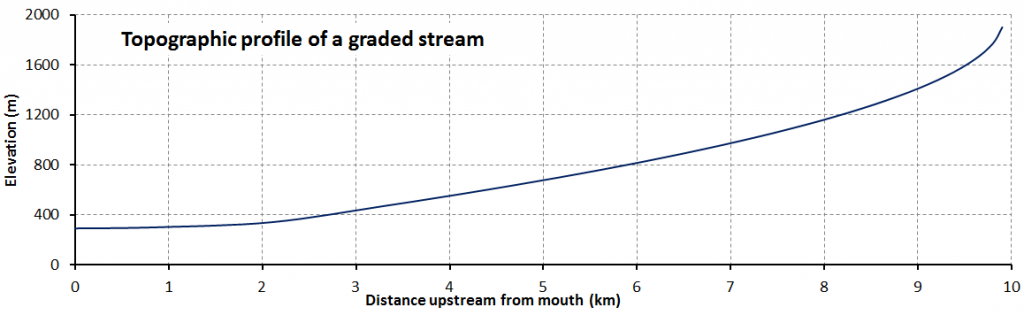

Over geological time, a stream will erode its drainage basin into a smooth profile similar to that shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). If we compare this with an ungraded stream like Cawston Creek (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), we can see that graded streams are steepest in their headwaters and their gradient gradually decreases toward their mouths. Ungraded streams have steep sections at various points, and typically have rapids and waterfalls at numerous locations along their lengths.

A graded stream can become ungraded if there is renewed tectonic uplift, or if there is a change in the base level, either because of tectonic uplift or some other reason. As stated earlier, the base level of Cawston Creek is defined by the level of the Similkameen River, but this can change, and has done so in the past. Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows the valley of the Similkameen River in the Keremeos area. The river channel is just beyond the row of trees. The green field in the distance is underlain by material eroded from the hills behind and deposited by a small creek (not Cawston Creek) adjacent to the Similkameen River when its level was higher than it is now. Sometime in the past several centuries, the Similkameen River eroded down through these deposits (forming the steep bank on the other side of the river), and the base level of the small creek was lowered by about 10 meters. Over the next few centuries, this creek will seek to become graded again by eroding down through its own alluvial fan.

Another example of a change in base level can be seen along the Juan de Fuca Trail on southwestern Vancouver Island. As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\), many of the small streams along this part of the coast flow into the ocean as waterfalls. It is evident that the land in this area has risen by about 5 meters in the past few thousand years, probably in response to deglaciation. The streams that used to flow directly into the ocean now have a lot of down-cutting to do to become regraded.

The ocean is the ultimate base level, but lakes and other rivers act as base levels for many smaller streams. We can create an artificial base level on a stream by constructing a dam, as illustrated in Exercise 13.2.

When a dam is built on a stream, a reservoir (artificial lake) forms behind the dam. This temporarily (for many decades at least) creates a new base level for the part of the stream above the reservoir.

How does the formation of a reservoir affect the stream where it enters the reservoir, and what happens to the sediment it was carrying?

The water leaving the dam has no sediment in it. How does this affect the stream below the dam?

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 13.2 answers.

Sediments accumulate within the flood plain of a stream, and then, if the base level falls, or if there is less sediment to deposit, the stream may cut down through those existing sediments to form terraces. A terrace on the Similkameen River is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) and some on the Fraser River are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\). The Fraser River photo shows at least two levels of terraces.

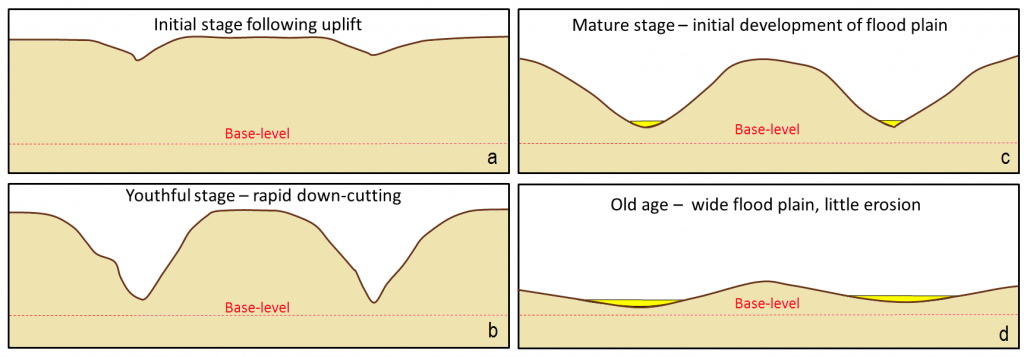

In the late 19th century, American geologist William Davis proposed that streams and the surrounding terrain develop in a cycle of erosion (Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)). Following tectonic uplift, streams erode quickly, developing deep V-shaped valleys that tend to follow relatively straight paths. Gradients are high, and profiles are ungraded. Rapids and waterfalls are common. During the mature stage, streams erode wider valleys and start to deposit thick sediment layers. Gradients are slowly reduced and grading increases. In old age, streams are surrounded by rolling hills, and they occupy wide sediment-filled valleys. Meandering patterns are common.

Davis’s work was done long before the idea of plate tectonics, and he was not familiar with the impacts of glacial erosion on streams and their environments. While some parts of his theory are out of date, it is still a useful way to understand streams and their evolution.

Image Descriptions

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) image description: Cawston Creek is a drainage basin made up of a number of small streams that flow into the Similkameen River. The Cawston Creek drainage basin also has a smaller tributary drainage basin that flows into it. [Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)]

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) image description: The graph shows the topographical profile of the Cawston Creek channel. Starting at 10 kilometers from the Similkameen River, the channel is at an elevation of 1800 meters. It flows downhill towards the river at a steady decline for seven kilometers. At three kilometers from the Similkameen River at an elevation of 275 meters, the channel levels out and stays at that elevation until it joins with the Similkameen River. This is conveyed in the following table.

| Distance from the Similkameen River (kilometers) | Elevation (meters) |

|---|---|

| 10 | 1,800 |

| 9 | 1,750 |

| 8 | 1,500 |

| 7 | 1,300 |

| 6 | 1,125 |

| 5 | 950 |

| 4 | 600 |

| 3 | 280 |

| 2 | 275 |

| 1 | 275 |

| 0 | 275 |

To determine the gradient of the stream, you must divide the change in elevation (rise) by the change in distance (run). For example, the elevation at 4.5 kilometers from the river is 800 meters and at 8.0 kilometers from the river, the elevation is 1500 meters. That means that in 3.5 kilometers (run), elevation increased by 700 meters (rise). To determine the gradient, you must divide rise (700 meters) by run (3.5 kilometers), which equals a vertical increase of 200 meters per kilometre.

[Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)]

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) image description: Three types of drainage patterns:

- Dendritic: a pattern of drainage channels that resembles the branches in a tree.

- Trellis: a drainage pattern in which tributaries typically flow parallel to one other but meet at right angles.

- Rectangular: a drainage pattern in which tributaries typically flow at right angles to each other and meet at right angles.

[Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)]

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) image description: Two types of drainage patterns:

- Deranged: a pattern of drainage channels that is chaotic.

- Radial: a pattern of streams radiating out from a central point, typically an isolated mountain.

[Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)]

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) image description: The topographic profile of a typical graded stream. While the topographical profile of Cawston Creek fell at a steady rate and then leveled out for the last three kilometers, the topographical profile of a typical graded stream starts out steep, but the slope (or gradient) gradually decreases towards the bottom to form a soft curve. [Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)]

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) image description: The Fraser River snaking through a channel that it has worn down over the years. The sides of the bank rise steeply, level out, and then rise again to produce terraces. [Return to Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)]

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) image description: William Davis’s cycle of erosion.

- Initial stage: A tectonic uplift forms two sharp valleys on each side.

- Youthful stage: Steams flowing through those valleys erode the surrounding earth quickly and cut deep to form sharp V’s.

- Mature stage: The streams become wider and the banks more gradual. This marks the initial development of a flood plain.

- Old age: Steams for a wide flood plain where little erosion occurs.

Media Attributions

- Figures 13.2.1, 13.2.2, 13.2.4, 13.2.5, 13.2.6, 13.2.7, 13.2.8, 13.2.9, 13.2.11: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Image by Metro Vancouver. Used with permission.

- Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Image by Marie Betcher. Used with permission.