5.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 6082

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Introduction

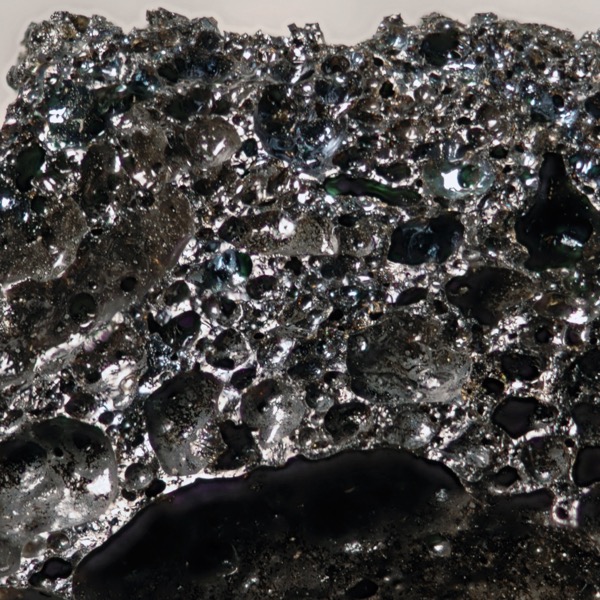

All rocks found on the Earth are classified into one of three groups: igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic. This rock classification is based on the origin of each of these rock type or the rock-forming process that formed the rock. The focus of this chapter will be on igneous rocks, which are the only rocks that form from what was once a molten or liquid state. Therefore, based on their mode of origin, igneous rocks are defined as those rock types that form by the cooling of magma or lava. You would be right in thinking that there is more to the classification of igneous rocks than stated in the previous sentence, as there are dozens of different igneous rocks that are considered commonplace, dozens of more types that are less common, and also quite a few igneous rock types that are quite scarce. Yet each igneous rock has a name that distinguishes it from all the rest. So, if they all start out as molten material (magma or lava), which must harden to form a rock, then it is logical to assume that these igneous rocks differ from one another primarily due to:

- the original composition of the molten material from which the rock is derived, and

- the cooling process of the molten material that ended up forming the rock. These two parameters— composition and texture— define the classification of igneous rocks. Igneous rock composition refers to what is in the rock (the chemical composition or the minerals that are present), and a rocks’ texture refers to the features that we see in the rock, such as the mineral sizes or the presence of glass, fragmented material, or vesicles (holes) in the igneous rock.

In this module you will be learning about intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks. Igneous rocks are very commonly encountered in nature. Well-known examples are the basalt rocks of Hawaii that formed during volcanic eruptions on the islands. However, igneous rocks have formed throughout Earth’s history and, through the process of plate tectonics, are often located at great distances from active volcanoes. For example, in the Catalina Mountains to the north of Tucson, there are many examples of igneous rocks, including three sills of granite that formed about 50 million years ago through an intrusion into an older granite unit. In this module, you will learn about the different types of igneous deposits, including sills, and how composition is related to the environment in which the rocks formed.

Select an image to view larger

Module Objectives

At the completion of this module you will be able to:

- Explain the rock cycle and the processes involved.

- Name and describe the different types of intrusive and extrusive igneous deposits.

- Describe the composition of different types of igneous rocks and explain the processes involved in their formation.

- Explain which tectonic environment is associated with which kinds of igneous rock.

Activities Overview

See the Schedule of Work for dates of availability and due dates.

Be sure to read through the directions for all of this module’s activities before getting started so that you can plan your time accordingly. You are expected to work on this course throughout the week.

Read

Physical Geology by Steven Earle

- Chapter 3 (Intrusive Igneous Rocks)

Module 5 Assignment: Igneous Rock Lab

10 points

After you complete the reading, you can start working on Module 5 Assignment – Igneous Rock Lab.

Module 5 Quiz

10 points

Module 5 Quiz has 10 multiple-choice questions and is based on the content of the Module 5 readings and Assignment 5.

The quiz is worth a total of 10 points (1 points per question). You will have only 10 minutes to complete the quiz, and you may take this quiz only once. Note: that is not enough time to look up the answers!

Make sure that you fully understand all of the concepts presented and study for this quiz as though it were going to be proctored in a classroom, or you will likely find yourself running out of time.

Keep track of the time, and be sure to look over your full quiz results after you have submitted it for a grade.

Exam 1

75 points

Exam 1 is due this module. You will be asked to put your knowledge to work in the Great Outdoors or at your local rock shop! You will be assembling a mineral kit with 5 minerals of your choice, composed of samples you have collected yourself or purchased individually. As a result, your kit will be customized according to your own interests.

You can read more about this in the Exam 1 Instructions.

This is a “work-at-home” project. You will submit the results from your project in the Assignments tool.

Check the Course Schedule for due date.

Your Questions and Concerns…

Please contact me if you have any questions or concerns.

General course questions: If your question is of a general nature such that other students would benefit from the answer, then go to the discussions area and post it as a question thread in the “General course questions” discussion area.

Personal questions: If your question is personal, (e.g. regarding my comments to you specifically), then send me an email from within this course.