4.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 6080

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Module 4

Minerals

Introduction

In this module you will be learning about the building blocks of all of the materials that exist on the Earth. Atoms, comprised of protons, electrons and neutrons, form the elements of the Periodic Table. In turn, different elements combine to form different types of minerals. The properties of different materials are directly dependent on the elements that they contain. During this module, you will be learning about different minerals and carrying out a lab experiment to see first hand how properties vary from mineral to mineral.

Have you used a mineral yet today? While many people may initially say no, answer these questions: Have you brushed your teeth? Have you eaten anything that might contain salt? Did you put on makeup this morning, or do you have painted fingernails or toenails? Have you used a cellphone? What about a car, bike, or public transportation? If you have done any of those things, you have used at least one mineral, and in many cases you have used a great number of minerals. Minerals are very useful and common in everyday products, but most people do not even realize it.

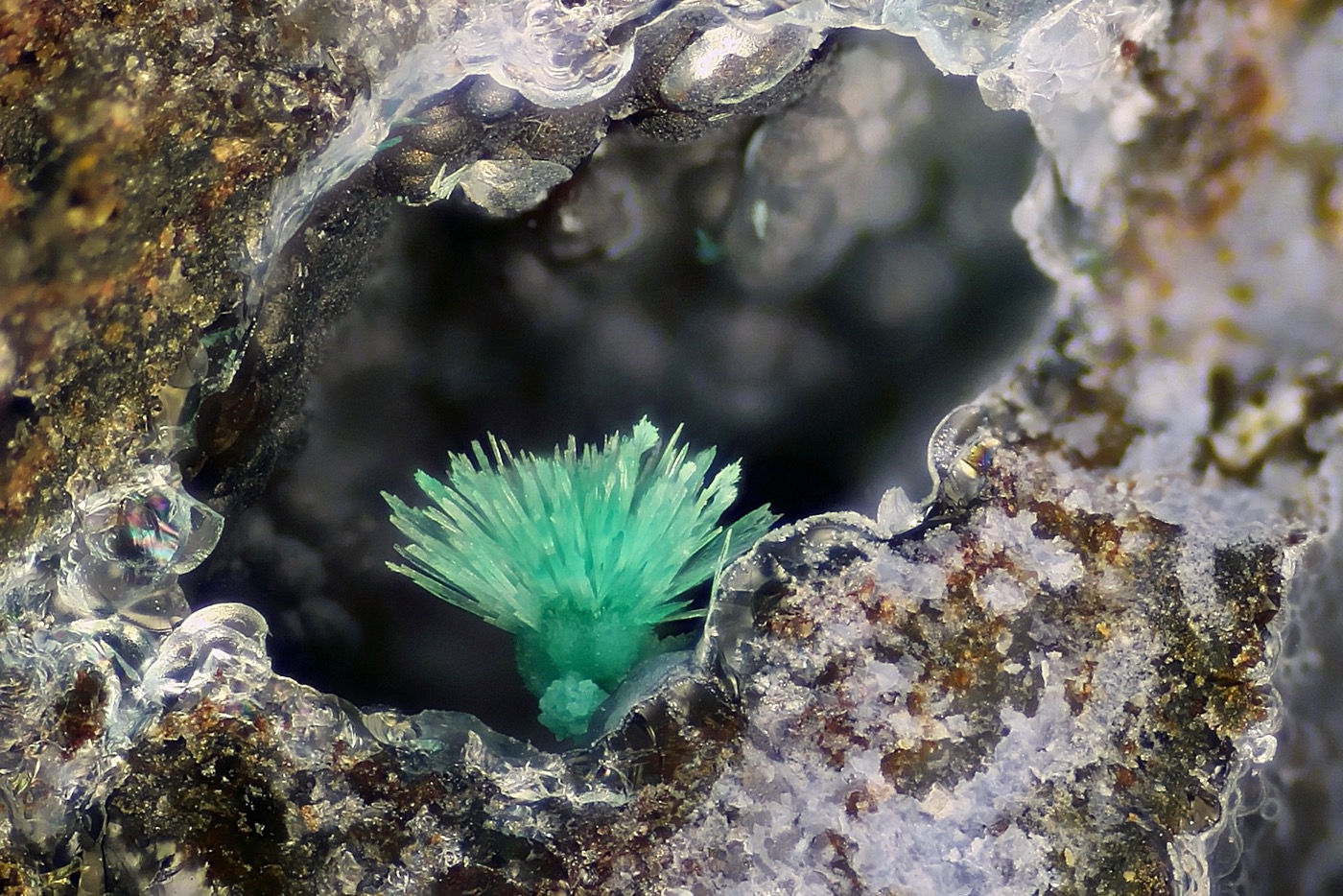

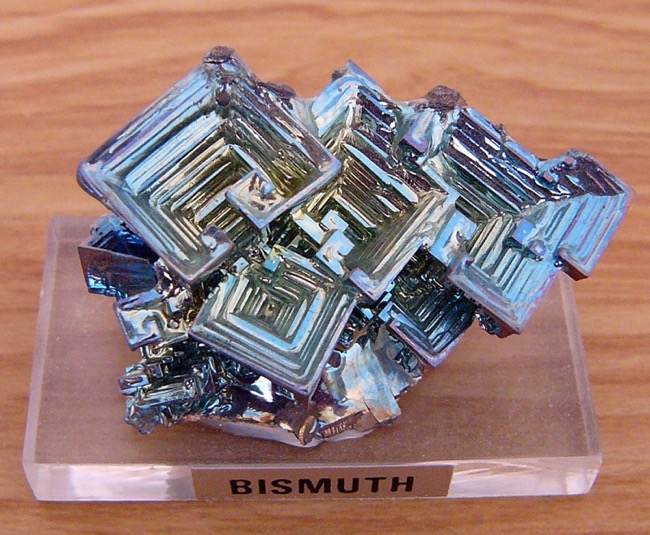

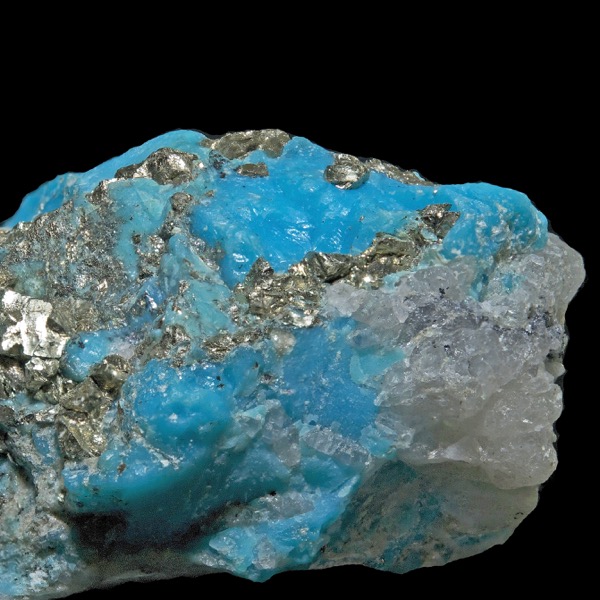

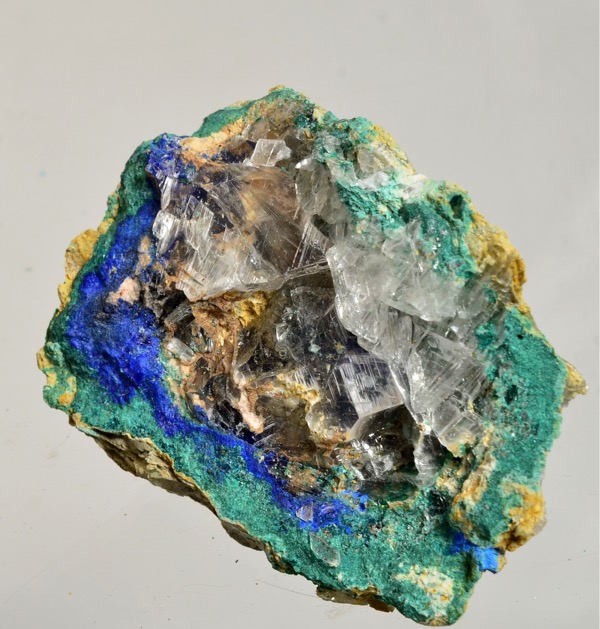

A mineral is defined as a naturally occurring, inorganic solid with a definite chemical composition and a characteristic crystalline structure. Let’s break that definition down. By naturally occurring, it means that anything humans have created, like the beautiful synthetic bismuth in the figure below, does not count as a mineral.

To be an inorganic solid, the mineral must not be composed of the complex carbon molecules that are characteristic of life and must be in the solid state, rather than vapor or liquid. This means that water, a liquid, is not a mineral, while ice, a solid, would be (as long as it is not man-made). A definite chemical composition refers to the chemical formula of a mineral. For most minerals, this does not vary (for example, halite is NaCl), though some minerals have a range of compositions, since one element can substitute for another of similar size and charge (for example, the chemical formula for olivine is (Mg,Fe)2SiO4, indicating its magnesium and iron content can vary). The atoms within minerals are lined up in an orderly fashion, so that the characteristic crystalline structure is just an outward manifestation of the internal atomic arrangement. Minerals are not only important for their many uses, but also as the building blocks of rocks.

Select an image to view larger

Module Objectives

At the completion of this module you will be able to:

- Describe what an atom is and identify the elements that are important in geology.

- Name common minerals and describe their structure.

- Explain how to identify a mineral from its physical properties, and give examples for common minerals.

Activities Overview

See the Schedule of Work for dates of availability and due dates.

Be sure to read through the directions for all of this module’s activities before getting started so that you can plan your time accordingly. You are expected to work on this course throughout the week.

Read

Physical Geology by Steven Earle

- Chapter 2 (Minerals)

Optional Resources

Module 4 Quiz

10 points

Module 4 Quiz has 10 multiple-choice questions and is based on the content of the Module 4 readings.

The quiz is worth a total of 10 points (1 points per question). You will have only 10 minutes to complete the quiz, and you may take this quiz only once. Note: that is not enough time to look up the answers!

Make sure that you fully understand all of the concepts presented and study for this quiz as though it were going to be proctored in a classroom, or you will likely find yourself running out of time.

Keep track of the time, and be sure to look over your full quiz results after you have submitted it for a grade.

Prepare for Exam 1

75 points

For Exam 1, you will be asked to put your knowledge to work in the Great Outdoors or at your local rock shop! You will be assembling a mineral kit with 5 minerals of your choice, composed of samples you have collected yourself or purchased individually. As a result, your kit will be customized according to your own interests.

You can read more about this in the Exam 1 Instructions.

This is a “take-home” project. You will submit the results from your project in the Assignments tool during the week of Module 5.

Keep in mind that even though this exam is available for viewing a week earlier than the other exams you will take in this course, you will not be introduced to some of the content you need to complete this project until Module 5, so you are advised to keep this in mind as you start thinking about your project.

Your Questions and Concerns…

Please contact me if you have any questions or concerns.

General course questions: If your question is of a general nature such that other students would benefit from the answer, then go to the discussions area and post it as a question thread in the “General course questions” discussion area.

Personal questions: If your question is personal, (e.g. regarding my comments to you specifically), then send me an email from within this course.