3.5: The Rock Cycle

- Page ID

- 20762

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

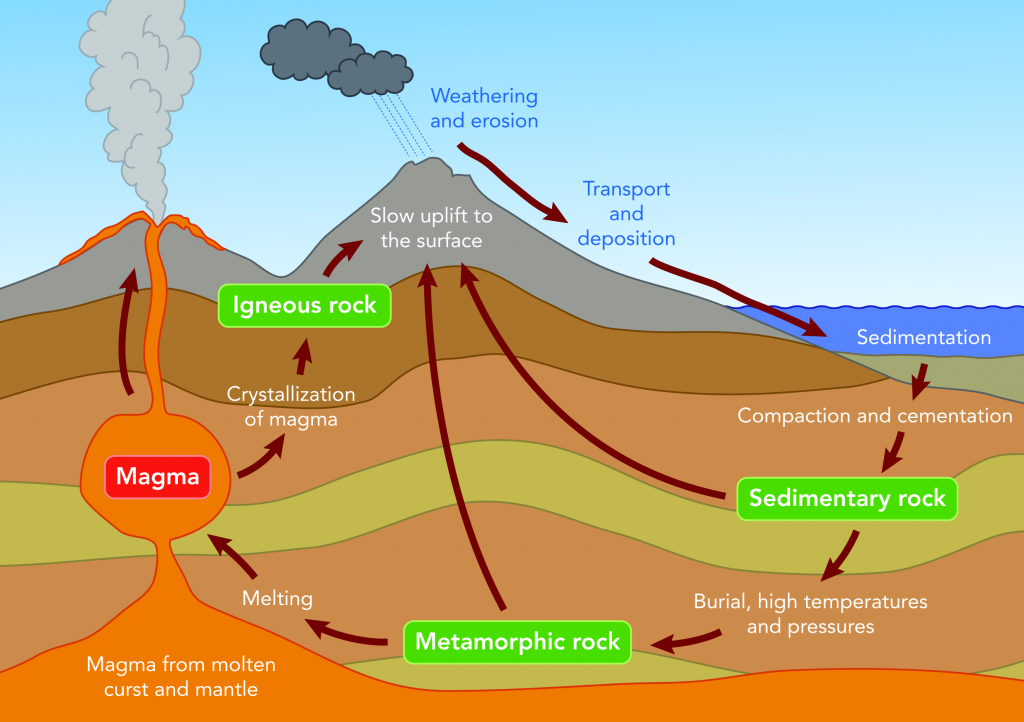

The most fundamental view of Earth materials is the rock cycle, which presents the primary materials that comprise the Earth and describes the processes by which they form and relate to each other. The rock cycle is usually said to begin with a hot molten liquid rock called magma or lava. Magma forms under the Earth’s surface in the crust or mantle and erupts on Earth’s surface as lava. When magma or lava cools, it solidifies by crystallization in which minerals grow within the magma or lava. The rock that results from this is an igneous rock from the Latin word ignis, meaning “fire.”

Igneous rocks, as well as other types of rocks on Earth’s surface, are exposed to weathering and erosion processes to produce sediments. Weathering is the physical and chemical breakdown of rocks into smaller fragments, and erosion is the removal of those fragments from their original location. Once igneous rocks are broken down and transported, these fragments or grains are considered sediments. Sediments such as gravel, sand, silt, and clay can be transported by water in the form of streams, ice in the form of glaciers, and air in the form of wind. Sediments ultimately come to rest in a process known as deposition. The deposited sediments accumulate in place, often underwater such as a shallow marine environment, get buried.

Within the burial process, the sediments go through compaction by the weight of overlying sediments and cementation as minerals in groundwater glue the sediments together. The process of compacting and cementing sediments together is lithification, and lithified sediments are considered a sedimentaryrock, such as sandstone and shale. Other sedimentary rocks, known as chemical sedimentary rocks, are not made of weathered and eroded sedimentary fragments. The direct chemical precipitation instead makes them of minerals.

Pre-existing rocks may be metamorphosed into a metamorphicrock, meta- means “change”, -morphos means “form” or “shape.” When rocks are subjected to extreme increases in temperatures or pressures, the minerals alter into enlarged crystals, or entirely new minerals with a similar chemical make up. These elevated temperatures and pressures can occur when rocks are buried deep within the Earth’s crust, or they encounter hot magma or lava. In some cases, the temperature and pressure conditions can allow rocks to melt and create magma and lava, showing the cyclical nature of the rock cycle as new rocks are born. Click here to learn more about various igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks from the Utah Geologic Survey (UGS).

Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks form from the cooling and hardening of molten magma in many different environments. Their composition and texture identify these rocks. More than 700 distinct types of igneous rocks are known.

Magma Composition

The rock beneath the Earth’s surface is sometimes heated to high enough temperatures that it melts to create magma. Different magmas have a different composition and contain whatever elements were in the rock that melted. Magma also contains gases. (Reading: Types of Rocks | Geology, n.d.) The main elements are the same as the elements found in the crust. Whether rock melts to create magma depends on:

- Temperature: Temperature increases with depth, so melting is more likely to occur at greater depths.

- Pressure: Pressure increases with depth, but increased pressure raises the melting temperature, so melting is less likely to occur at higher pressures.

- Water: The addition of water changes the melting point of rock. As the number of water molecules increases, the melting point decreases.

- Rockcomposition: Minerals melt at different temperatures, so the temperature must be high enough to melt some minerals in the rock. The first mineral to melt from a rock will be quartz (if present), and the last will be olivine (if present).

As a rock heats up, the minerals that melt at the lowest temperatures will melt first. Partial melting occurs when the temperature on a rock is high enough to melt only some of the minerals in the rock. The minerals that will melt will be those that melt at lower temperatures. Fractional crystallization is the opposite of partial melting. This process describes the crystallization of different minerals as magma cools. (Igneous Rocks | Geology, n.d.)

Bowen’s Reaction Series indicates the temperatures at which minerals melt or crystallize. An understanding of the way atoms joins to form minerals leads to an understanding of how different igneous rocks form. Bowen’s Reaction Series also explains why some minerals are always found together, and some are never found together.

If the liquid separates from the solids at any time in partial melting or fractional crystallization, the liquid and solid chemical composition will be different. When that liquid crystallizes, the resulting igneous rock will have a different composition from the parent rock. (Reading: Types of Rocks | Geology, n.d.)

Intrusive Igneous Rock

Igneous rocks are called intrusive when they cool and solidify beneath the surface. Intrusive igneous rocks form plutons, and so are also called plutonic. A pluton is an igneous intrusive rock body that has cooled in the crust. When magma cools within the Earth, the cooling proceeds slowly. Intrusive igneous rocks cool slower than extrusive igneous rocks, which allows for more massive crystal structure to develop.

Igneous rocks make up most of the rocks on Earth. Most igneous rocks are buried below the surface and covered with sedimentary rocks or are buried beneath the ocean water. In some places, geological processes have brought igneous rocks to the surface. Yosemite is a classic example of intrusive igneous rock. The molten magma never reached Earth’s surface, so the molten material had millions of years to cool down slowly to form granite. Later, geologic forces and erosion have caused those granite plutons to surface as they are today.

Extrusive Igneous Rock

Igneous rocks are called extrusive when they cool and solidify above the surface. These rocks usually form from a volcano, so they are also called volcanic rocks. Extrusive igneous rocks cool much more rapidly than intrusive rocks, reducing the time for crystal structure to form within the rocks.

Cooling rate and gas content create a variety of rock textures. Lavas that cool exceptionally rapidly may have a glassy texture. Those with many holes from gas bubbles have a vesicular texture. (Igneous Rocks | Geology, n.d.)

Human Uses of Igneous Rock

Igneous rocks have a wide variety of uses, including to create buildings and statues, kitchen countertops, abrasive material for household products, or for smoothing skin. Ground-up pumice stone is sometimes added to toothpaste to function as an abrasive material to scrub teeth. Peridotite is sometimes mined for peridot, a type of olivine that is used in jewelry. Diorite was used extensively by ancient civilizations for vases and other decorative artwork and is still used for art today.

Sedimentary Rock

Sandstone is one of the common types of sedimentaryrocks that form from sediments. There are many other types. Sediments may include:

- Fragments of other rocks that often have been worn down into small pieces, such as sand, silt, or clay.

- Organic materials, or the remains of once-living organisms.

- Chemical precipitates, which are materials that get left behind after the water evaporates from a solution.

Rocks at the surface undergo mechanical and chemical weathering. These physical and chemical processes break the rock into smaller pieces. Physical weathering breaks the rocks apart, while chemicalweathering dissolves the less stable minerals. These original elements of the minerals end up in solution, and new minerals may form. Sediments are removed and transported by water, wind, ice, or gravity in a process called erosion.

Streams carry vast amounts of sediment. The more energy the water has, the larger the particle it can carry. A rushing river on a steep slope might be able to carry boulders. As this stream slows down, it no longer has the energy to carry large sediments and will drop them. A slower moving stream will only carry smaller particles.

Sediments are deposited on beaches and deserts, at the bottom of oceans, and in lakes, ponds, rivers, marshes, and swamps. Fast-moving avalanches and slow-moving glaciers can drop large piles of sediment. Wind can only transport sand and smaller particles. The type of sediment that is deposited will determine the type of sedimentary rock that can form. Distinct colors of sedimentary rock are determined by the environment where they are deposited. Red rocks form where oxygen is present, while darker sediments form when the environment is oxygen-poor. (Reading: Mining and Mineral Use | Geology, n.d.)

Sedimentary Rock Formation

Accumulated sediments harden into a rock by a process called lithification. Two essential steps are needed for sediments to lithify. Sediments are squeezed together by the weight of overlying sediments on top of them, called compaction. Cemented, non-organic sediments become clasticrocks. If organic material is included, they are bioclasticrocks.

Fluids fill in the spaces between the loose particles of sediment and crystallize to create a rock by cementation. When sediments settle out of calmer water, they form horizontal layers. One layer is deposited first, and another layer is deposited on top of it. So, each layer is younger than the layer beneath it. When the sediments harden, the layers are preserved. Sedimentary rocks formed by the crystallization of chemical precipitates are called chemical sedimentary rocks.

Biochemical sedimentary rocks form in the ocean or a salt lake. Living creatures remove ions, such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium, from the water to make shells or soft tissue. When the organism dies, it sinks to the ocean floor to become biochemical sediment, which may become compacted and cemented into solid rock. (Reading: Mining and Mineral Use | Geology, n.d.)

Human Use of Sedimentary Rock

Sedimentary rocks are used as building stones, although they are not as hard as igneous or metamorphic rocks. Sedimentary rocks are used in construction. Sand and gravel are used to make concrete; they are also used in asphalt. Many economically valuable resources come from sedimentary rocks. Iron ore and aluminum are two examples. (Reading: Mining and Mineral Use | Geology, n.d.)

Metamorphic Rock

Metamorphism is the addition of heat and/or pressure to existing rocks, which causes them to change physically and/or chemically so that they become a new rock. Metamorphic rocks may change so much that they may not resemble the original rock.

Any type of rock – igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic – can become a metamorphic rock. All that is needed is enough heat and/or pressure to alter the existing rock’s physical or chemical makeup without melting the rock entirely. Rocks change during metamorphism be-cause the minerals need to be stable under the new temperature and pressure conditions. The need for stability may cause the structure of minerals to rearrange and form new minerals. Ions may move between minerals to create minerals of the different chemical compositions. Hornfels, with its alternating bands of dark and light crystals, is an excellent example of how minerals rearrange themselves during metamorphism.

Extreme pressure may also lead to foliation, the flat layers that form in rocks as pressure squeezes the rocks. Foliation forms typically when pressure is exerted in only one direction. Metamorphic rocks may also be non-foliated. Quartzite and limestone are non-foliated. The two main types of metamorphism are both related to heat within Earth:

- Regional metamorphism: Changes in enormous quantities of rock over a wide area caused by extreme pressure from overlying rock or compression caused by geologic processes. Deep burial exposes the rock to hot temperatures.

- Contact metamorphism: Changes in a rock that is in contact with magma because of the magma’s extreme heat.

The Utah Geologic Survey has several resources related to landforms in Utah. They have also created a fun story map called GeoSights of popular geologic sights within the State of Utah.