9.5: Types of Volcanoes

- Page ID

- 2539

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)INTRODUCTION

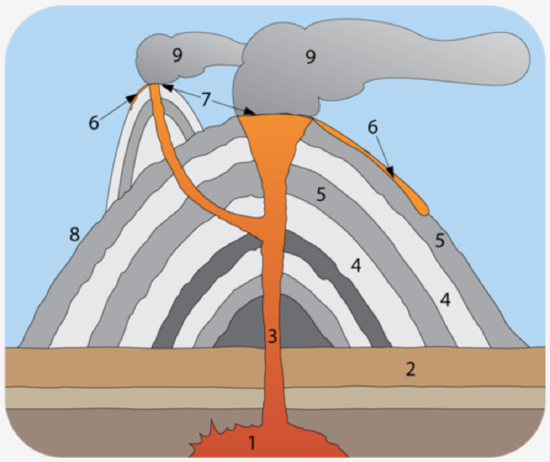

A volcano is a vent through which molten rock and gas escape from a magma chamber. Volcanoes differ in many features such as height, shape, and slope steepness. Some volcanoes are tall cones and others are just cracks in the ground (figure 1). As you might expect, the shape of a volcano is related to the composition of its magma.

COMPOSITE VOLCANOES

Composite volcanoes are made of felsic to intermediate rock. The viscosity of the lava means that eruptions at these volcanoes are often explosive (figure 2).

The viscous lava cannot travel far down the sides of the volcano before it solidifies, which creates the steep slopes of a composite volcano. Viscosity also causes some eruptions to explode as ash and small rocks. The volcano is constructed layer by layer, as ash and lava solidify, one upon the other (figure 3). The result is the classic cone shape of composite volcanoes.

SHIELD VOLCANOES

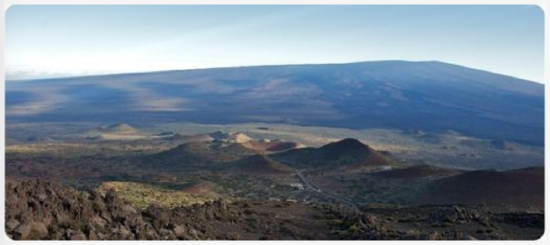

Shield volcanoes get their name from their shape. Although shield volcanoes are not steep, they may be very large. Shield volcanoes are common at spreading centers or intraplate hot spots (figure 4).

The lava that creates shield volcanoes is fluid and flows easily. The spreading lava creates the shield shape. Shield volcanoes are built by many layers over time and the layers are usually of very similar composition. The low viscosity also means that shield eruptions are non-explosive.

This Volcanoes 101 video from National Geographic discusses where volcanoes are found and what their properties come from:

CINDER CONES

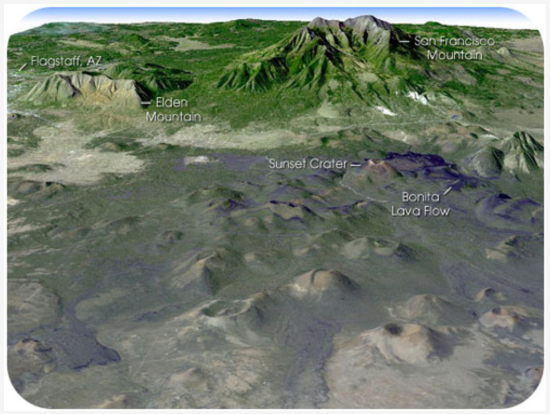

Cinder cones are the most common type of volcano. A cinder cone has a cone shape, but is much smaller than a composite volcano. Cinder cones rarely reach 300 meters in height but they have steep sides. Cinder cones grow rapidly, usually from a single eruption cycle (figure 5). Cinder cones are composed of small fragments of rock, such as pumice, piled on top of one another. The rock shoots up in the air and doesn’t fall far from the vent. The exact composition of a cinder cone depends on the composition of the lava ejected from the volcano. Cinder cones usually have a crater at the summit.

Cinder cones are often found near larger volcanoes (figure 6).

SUPERVOLCANOES

Supervolcano eruptions are extremely rare in Earth history. It’s a good thing because they are unimaginably large. A supervolcano must erupt more than 1,000 cubic km (240 cubic miles) of material, compared with 1.2 km3 for Mount St. Helens or 25 km3 for Mount Pinatubo, a large eruption in the Philippines in 1991. Not surprisingly, supervolcanoes are the most dangerous type of volcano.

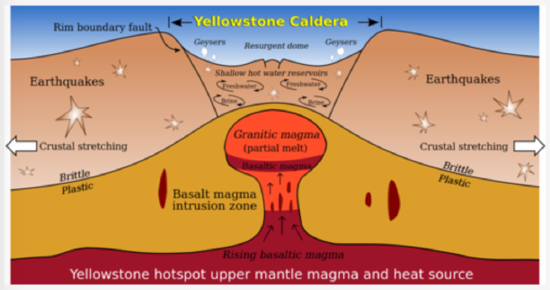

Supervolcanoes are a fairly new idea in volcanology. The exact cause of supervolcano eruptions is still debated. However, scientists think that a very large magma chamber erupts entirely in one catastrophic explosion. This creates a huge hole or caldera into which the surface collapses (figure 7).

The largest supervolcano in North America is beneath Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Yellowstone sits above a hotspot that has erupted catastrophically three times: 2.1 million, 1.3 million, and 640,000 years ago. Yellowstone has produced many smaller (but still enormous) eruptions more recently (figure 8). Fortunately, current activity at Yellowstone is limited to the region’s famous geysers.

Long Valley Caldera, south of Mono Lake in California, is the second largest supervolcano in North America (figure 9). Long Valley had an extremely hot and explosive rhyolite about 700,000 years ago. An earthquake swarm in 1980 alerted geologists to the possibility of a future eruption, but the quakes have since calmed down.

- This site provides and interactive image of the geological features of Long Valley Caldera.

A supervolcano could change life on Earth as we know it. Ash could block sunlight so much that photosynthesis would be reduced and global temperatures would plummet. Volcanic eruptions could have contributed to some of the mass extinctions in our planet’s history. No one knows when the next super eruption will be.

Interesting volcano videos are seen on National Geographic Videos, Environment Video, Natural Disasters, Earthquakes. One interesting one is “Mammoth Mountain,” which explores Hot Creek and the volcanic area it is a part of in California.

LESSON SUMMARY

- Composite, shield, cinder cones, and supervolcanoes are the main types of volcanoes.

- Composite volcanoes are tall, steep cones that produce explosive eruptions.

- Shield volcanoes form very large, gently sloped mounds from effusive eruptions.

- Cinder cones are the smallest volcanoes and result from accumulation of many small fragments of ejected material.

- An explosive eruption may create a caldera, a large hole into which the mountain collapses.

- Supervolcano eruptions are devastating but extremely rare in Earth history.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What skill does this content help you develop?

- What are the key topics covered in this content?

- How can the content in this section help you demonstrate mastery of a specific skill?

- What questions do you have about this content?

Contributors and Attributions

Original content from Kimberly Schulte (Columbia Basin College) and supplemented by Lumen Learning. The content on this page is copyrighted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.