9: Sierra Nevada

- Page ID

- 20343

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction to the Sierra Nevada

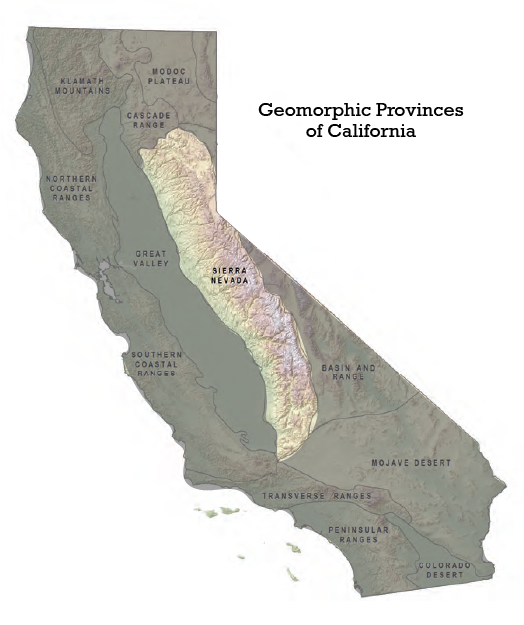

The Sierra Nevada province is a 644 km-long (400 mile) 80 km-wide (50 mile) region trending north-northwest and located primarily in central and eastern California. A small spur of the province called the Carson Range is just over the border in Nevada. It is bounded by the Cascade province to the north, the Basin and Range province to the east, and the Great Valley province to the west. The Garlock fault forms the southern boundary of of the Sierra Nevada province, separating it from the Mojave province (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\))

The most prominent feature of the Sierra Nevada province is its mountain range of the same name which boasts notable features such as the highest peak in the contiguous United States, Mount Whitney at 4,421 m (14,505 ft); Yosemite Valley and National Park; and Lake Tahoe, the largest alpine lake in North America.

The Sierra Nevada range of California has a complex geologic history that spans 210 million years. While the majority of what would become the Sierra Nevada Province started forming during the Mesozoic Era, what we see today did not exist and is very different from the Sierra Nevada of that time.

The Sierra Nevada Mountains began to form when a series of intrusive plutonic events began to formed much of the range's granitic rock, including iconic features like Half Dome and El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Over time, erosion and crustal extension gradually revealed plutonic granite formations at Earth's surface. Tectonic forces continued to uplift the emerging Sierra Nevada range, shaping it into the distinctive landscape we observe today.

During the Cenozoic Era, tectonic forces continued to uplift the Sierra Nevada, and the mountains were sculpted by glaciers during the Pleistocene, giving rise to the dramatic landscapes seen today.

This chapter explores the history of this region, including the emplacement, exhumation, and erosion of batholiths - magma chambers that fed a once extensive volcanic arc, the accumulation of gold deposits that would make the Sierra Nevada famous in recent times, and glacial evidence attesting to a changing climate in this region.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the Sierra Nevada province in terms of rock types, age, and tectonic development.

- Assess the geologic hazards and risks associated with the Sierra Nevada province.

- Describe the geologic processes involved the formation and preservation of gold.

- 9.1: The Sierra Nevada Today

- This page describes the Sierra Nevada Province, emphasizing its diverse landscapes, including rugged peaks and valleys of intrusive and metamorphic rocks, along with volcanic features. The region's Mediterranean climate leads to significant winter snowfall, essential for water supply. It notes the asymmetrical profile of the mountains, featuring Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the contiguous U.S.

- 9.2: Ancient Seas Form the Oldest Rocks

- This page explores the geological history of the Sierra Nevada, highlighting its ancient rocks from the Cambrian period to Mesozoic and Paleozoic formations. It details the tectonic and sedimentary evolution of key terranes like the Shoo Fly Complex and the Kings River ophiolite, shaped by subduction and accretion during events such as the Antler Orogeny.

- 9.3: The Sierra Nevada Batholith

- This page covers the formation and characteristics of plutonic rocks, focusing on their coarse-grained textures due to the slow cooling of magma, and highlights the Sierra Nevada Batholith as a key example. It also discusses jointing in these rocks, particularly in the Batholith, defining types like exfoliation jointing, which impacts rock erosion and stability.

- 9.4: Gold of the Sierra Nevada

- This page covers the formation, recovery techniques, and environmental impacts of gold deposits in California, specifically lode and placer gold. It discusses the geological processes that yield gold, the significance of the California Gold Rush, and the various methods for gold extraction, including panning and hydraulic mining.

- 9.5: Volcanic Features of the Sierra Nevada

- This page explores the geological complexities of the Sierra Nevada, highlighting ancient formations and recent volcanic activity influenced by tectonic processes. Key features include the Mono-Inyo Craters, Obsidian Dome, table mountains, and unique formations like the Devils Postpile. It discusses the significance of uplift, erosion, and former lava flows in shaping the landscape, emphasizing the ongoing volcanic and seismic activity.

- 9.6: Ice Shapes the Landscape

- This page discusses the formation and movement of glaciers in the Sierra Nevada, emphasizing their role in landscape erosion and the distinct features they create. Historical glaciations during the Pleistocene Epoch indicate past climatic conditions. It highlights the retreat of the Lyell and Maclure Glaciers in Yosemite National Park as indicators of climate change, affecting regional water resources.

- 9.7: Natural Hazards of the Sierra Nevada

- This page covers the Sierra Nevada's geologic hazards, including earthquakes, landslides, and the impact of climate change on these risks. It notes events like the Ferguson Slide of 2006, the influence of environmental conditions on wildfires and flooding, and highlights the need for mitigation and public education.

- 9.8: Chapter Summary

- Summary of key chapter points and items related to the Sierra Nevada Province.

- 9.9: Detailed Figure Descriptions

- Descriptions of complex images within this chapter, as well as additional guidance for users who may have difficulty perceiving images.

Thumbnail: "Sierra Nevada Province" is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 by Allison Jones.