13.4: Desert Landforms

- Page ID

- 32250

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In the American Southwest, as streams emerge into the valleys from the adjacent mountains, they create desert landforms called alluvial fans. When the stream emerges from the narrow canyon, the flow is no longer constrained by the canyon walls [18] and spreads out. At the lower slope angle, the water slows down [17] and drops its coarser load. As the channel fills with this conglomeratic material, the stream is deflected around it. This process develops a system of radial distributary channels in a process similar to how a delta is made by a river entering a body of water [18]. The fan-shaped feature called an alluvial fan.

Alluvial fans continue to grow and may eventually coalesce with neighboring fans to form an apron of alluvium along the mountain front called a bajada [19].

As the mountains erode away and the sediment accumulates first in alluvial fans, then bajadas, the mountains eventually are buried in their own erosional debris. Such buried mountain remnants are called inselbergs [20], “island mountains,” as first described by the German geologist Wilhelm Bornhardt (1864-1946).

Where the desert valley is an enclosed basin, i.e. streams entering it do not drain out but the water is removed by evaporation, a dry lake bed is formed called a playa.

Playas are among the flattest of all landforms. Such a dry lake bed may cover a large area and be filled after a heavy thunderstorm to only a few inches deep. Playa lakes and desert streams that flow only after rainstorms are called intermittent or ephemeral. Because of intense thunderstorms, the volume of water transported by ephemeral dtrainage in arid environments can be substantial during a short period of time. Desert soil structures lack organic matter that promotes infiltration by absorbing water. Instead of percolating into the soil, the runoff compacts the ground surface, making the soil hydrophobic or water-repellant. Because of this hardpan surface, ephemeral streams may gather water across large areas, suddenly filling with water from storms many miles away.

High-volume ephemeral flows, called flash floods, may move as sheet flows or sheetwash, as well as be channeled through normally dry riverbeds called arroyos or through canyons. Flash floods are a major factor in desert deposition. Dry channels can fill quickly with ephemeral drainage, creating a mass of water and debris that charges down the arroyo, and even overflowing the banks. Flash floods pose a serious hazard for desert travelers because the storm activity feeding the runoff may be miles away. People hiking or camping in arroyos that have been bone dry for months or years have been swept away by sudden flash floods.

Sand

The popular concept of a typical desert is a broad expanse of sand. Geologically, deserts defined by a lack of water and arid regions resembling a sea of sand belong to the category of desert call an erg. An erg consists of fine-grained, loose sand, often blown by aeolian forces (wind) into dunes [21]. Probably the best-known erg is the Rub’ al Khali, which means Empty Quarter, of the Arabian Peninsula. Ergs are also found in Colorado (Great Sand Dunes National Park), Utah (Little Sahara Recreation Area), New Mexico (White Sands National Monument), and California (parts of Death Valley National Park). Ergs are not restricted to deserts, but may form anywhere there is a substantial supply of sand, including as far north as 60°N in Saskatchewan, Canada in the Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park. Coastal ergs exist along lakes and oceans as well, and can be found in places like Oregon, Michigan, and Indiana.

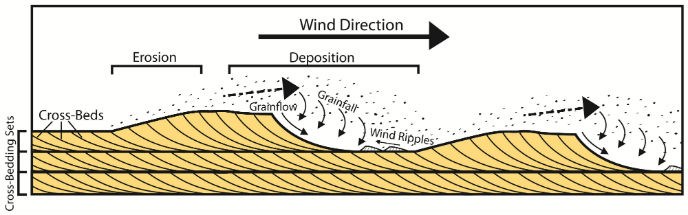

An internal cross section of a sand dune shows a feature called cross-bedding. As wind blows up the windward side of the dune, it carries sand to the dune crest, depositing layers of sand parallel to the windward (or “stoss”) side. The sand builds up the crest of the dune and pours over the top until the leeward (downwind or slip) face of the dune reaches the angle of repose, the maximum angle which will support the sand pile. Dunes are unstable features and move as the sand erodes from the stoss side and continues to drop down the leeward side covering previous stoss and slip-face layers and creating the cross-beds. Mostly, these are reworked over and over again, but occasionally, the features are preserved in a depression, then lithified. Shifting wind directions and abundant sand sources create chaotic patterns of cross-beds like those seen in Zion National Park of Utah.

In the Mesozoic Era, Utah was covered by a series of ergs, with the thickest in Southern Utah, which lithified into sandstone. Perhaps the best known of these sandstone formations is the Navajo Sandstone of Jurassic age. This formation consists of the dramatic cliffs and spires in Zion National Park and covers a large part of the Colorado Plateau. In Arches National Park, a later series of sand dunes covered the Navajo Sandstone and lithified to become the Entrada Formation also during the Jurassic. Erosion of overlying layers exposed fins of the underlying Entrada Sandstone and carved out weaker parts of the fins forming the arches.

As the cement that holds the grains together in these modern sand cliffs disintegrates and the freed grains gather at the base of the cliffs and move down the washes, sand grains may be recycled and redeposited. These Mesozoic sand ergs may represent ancient quartz sands recycled many times from igneous origins in the early Precambrian, just passing now through another cycle of erosion and deposition. One example of this is Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park in Southwestern Utah, which contains sand that is being eroded from the Navajo Sandstone forming new dunes.

Dune Types

Dunes are complex features formed by a combination of wind direction and sand supply, in some cases interacting with vegetation. There are several types of dunes representing the variable of wind direction, sand supply, and vegetative anchoring. Barchan dunes or crescent dunes form where sand supply is limited and there is a fairly constant wind direction. Barchans move downwind and develop a crescent shape with wings on either side of a dune crest. Barchans are known to actually move over homes, even towns.

Longitudinal dunes or linear dunes form where sand supply is greater and the wind blows around a dominant direction, in a back-and-forth manner. They may form ridges tens of meters high lined up with the predominant wind directions.

Parabolic dunes form where vegetation anchors parts of the sand and unanchored parts blowout. Parabolic dune shape is similar to barchan dunes but usually reversed, and it is determined more by the anchoring vegetation than a strict parabolic form.

Star dunes form where the wind direction is variable in all directions. Sand supply can range from limited to quite abundant. It is the variation in wind direction that forms the star.

References

17. Hooke, R. L. Processes on arid-region alluvial fans. J. Geol. 75, 438–460 (1967).

18. Boggs, S. J. Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy. (Pearson, 2011).

19. Easterbrook, D. J. Surface processes and landforms. (Pearson College Division, 1999).

20. King, L. C. Canons of landscape evolution. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 64, 721–752 (1953).