5.3: Measuring Earthquakes

- Page ID

- 33115

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)There are two main ways to measure earthquakes. The first of these is an estimate of the energy released, and the value is referred to as magnitude. This is the number that is typically first released by the press when a big earthquake happens. It is often referred to as “Richter magnitude”, and it estimates the amount of energy released.

The other way of assessing the impact of an earthquake is to assess what people felt and how much damage was done. This is known as intensity. Intensity values are assigned to locations, rather than to the earthquake itself, and intensity can vary widely therefore, depending on the proximity to the earthquake and the type of ground underneath.

Earthquake Magnitude

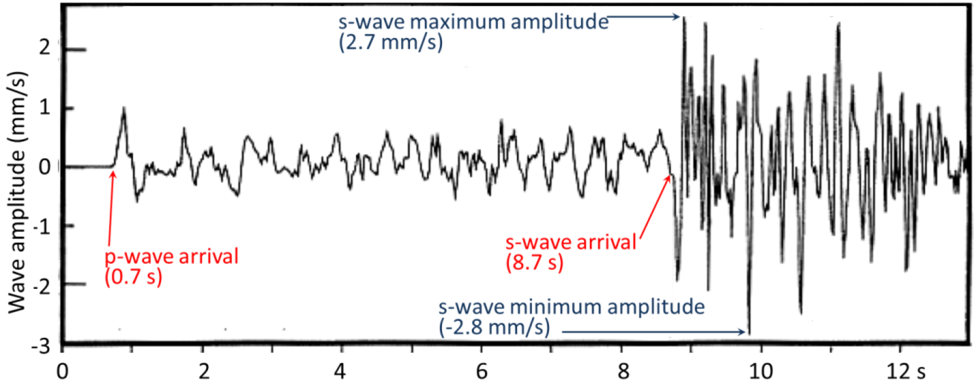

Before we look more closely at magnitude, we need to review what we know about body waves (waves that travel through the Earth), and also look at surface waves (waves that travel along the Earth's surface). Body waves are of two types, P or primary or compression waves (like the compression of the coils of a spring), and S or secondary or shear waves (like the flick of a rope). An example of P and S seismic records is shown on Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). The critical parameters for the measurement of Richter magnitude are labeled, including the time interval between the arrival of the P and S waves—which is used to determine the distance from the earthquake to the seismic station, and the amplitude of the S waves—which is used to estimate the magnitude.

When a body wave (P or S) reaches the Earth’s surface some of its energy is transformed into surface waves, of which there are two main types, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). Rayleigh waves are characterized by vertical motion of the ground surface, like waves on water, while Love waves are characterized by horizontal motion. Both Rayleigh and Love waves are about 90% as fast as S waves (so they arrive later at a seismic station). Surface waves typically have greater amplitudes than body waves, and they do more damage.

Two other important terms from the perspective of describing earthquakes are hypocenter and epicenter. The hypocenter is the actual location of an individual earthquake shock at depth in the ground, and the epicenter is the point on the land surface directly above the hypocenter (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Because of the increasing size of cities in earthquake-prone areas (e.g., China, Japan, California and Turkey) and the increasing sophistication of infrastructure, it is becoming important to have very rapid warnings, and magnitude estimates of earthquakes that have already happened. This can be achieved by using P-wave data because P waves arrive first at seismic stations, in many cases several seconds ahead of the more damaging S waves and surface waves. Operators of electrical grids, pipelines, trains and other infrastructure can use the information to automatically shut systems down so that damage and casualties can be limited.

The magnitude scale is logarithmic, in fact the amount of energy released by an earthquake of magnitude 4 is 32 times higher than that released by one of magnitude 3, and this ratio applies to all intervals in the scale. If we assign an arbitrary energy level of 1 unit to a magnitude 1 earthquake the energy for quakes up to magnitude 8 will be as shown on the following list:

| Magnitude | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Energy | 1 | 32 | 1024 | 32,768 | 1,048,576 | 33.5 million | 1.1 billion | 34.6 billion |

In any given year when there is a large earthquake on Earth (M 8 or 9) the amount of energy released by that one event will likely exceed the energy released by all smaller events combined.

Earthquake Intensity

The intensity of earthquake shaking at any location is determined by the magnitude of the earthquake and its distance, but also by the type of underlying rock or unconsolidated materials. If buildings are present, the size and type of building are also important.

Intensity scales were first used in the late 19th century, and then adapted in the early 20th century by Giuseppe Mercalli and modified later by others to form what we know call the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Intensity estimates are important because they allow us to characterize parts of any region into areas that are especially prone to strong shaking versus those that are not. The key factor in this regard is the nature of the underlying geological materials, and the weaker those are the more likely it is that there will be strong shaking. Areas underlain by strong solid bedrock tend to experience much less shaking that those underlain by unconsolidated river or lake sediments.

An example of this amplifying effect is provided by the 1985 M8 earthquake which struck the Pacific coast Michoacán region of western Mexico, about 350 km southwest of Mexico City. There was relatively little damage in the area around the epicenter, but there was tremendous damage and about 5000 deaths in heavily populated Mexico City. The key reason for this is that Mexico City was built largely on the unconsolidated and water-saturated sediment of former Lake Texcoco. These sediments resonate at a frequency of about 2 seconds, which was similar to the frequency of the body waves that reached the city.[1] For the same reason that a powerful opera singer can break a wine glass by singing the right note, the seismic shaking was amplified by the lake sediments. Survivors of the disaster recounted that the ground in some areas moved up and down by about 20 cm every 2 seconds for over 2 minutes. Damage was greatest to buildings between 5 and 15 stories tall, because they also resonated at around 2 seconds, and amplified the shaking.

Media Attributions

- Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Steven Earle, CC BY 4.0, after a Open Government Licence – Canada image provided by Natural Resources Canada

- Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Modified by Steven Earle, from images via Wikipedia: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Raylei...leigh_wave.jpg, Public domain, and https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Love_w...:Love_wave.jpg, CC BY 4.0

- Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Steven Earle, CC BY 4.0

- Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Steven Earle, CC BY 4.0, based on the modified scale by the US Geological Survey (public domain), https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards...center_objects

- An earthquake creates seismic waves with a wide range of frequencies. The fast-vibrating shorter wavelength waves get absorbed by strong bedrock because strong rock has a fast natural vibration frequency. The slow-vibrating longer wavelength waves can travel a long way through the solid rocks of the crust (because they don't match its natural vibration frequency and are not absorbed), and these are the waves that reached Mexico City in 1985. Their slow frequencies matched the natural frequency of the sediments underneath the city. ↵