2.2: The Atmosphere’s Pressure Structure - Hydrostatic Equilibrium

- Page ID

- 3356

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The atmosphere’s vertical pressure structure plays a critical role in weather and climate. We all know that pressure decreases with height, but do you know why?

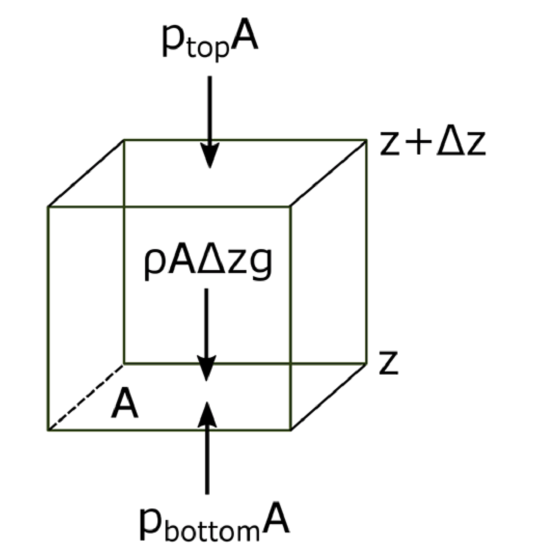

The atmosphere’s basic pressure structure is determined by the hydrostatic balance of forces. To a good approximation, every air parcel is acted on by three forces that are in balance, leading to no net force. Since they are in balance for any air parcel, the air can be assumed to be static or moving at a constant velocity.

There are 3 forces that determine hydrostatic balance:

- One force is downwards (negative) onto the top of the cuboid from the pressure, p, of the fluid above it. It is, from the definition of pressure, \[F_{t o p}=-p_{t o p} A\]

- Similarly, the force on the volume element from the pressure of the fluid below pushing upwards (positive) is: \[F_{\text {bottom}}=p_{\text {bottom}} A\]

- Finally, the weight of the volume element causes a force downwards. If the density is ρ, the volume is V, which is simply the horizontal area Atimes the vertical height, Δz, and g the standard gravity, then: \[F_{\text {weight}}=-\rho V g=-\rho g A \Delta z\]

By balancing these forces, the total force on the fluid is:

\[\sum F=F_{b o t t o m}+F_{t o p}+F_{w e i g h t}=p_{b o t t o m} A-p_{t o p} A-\rho \mathrm{gA} \Delta z\]

This sum equals zero if the air's velocity is constant or zero. Dividing by A,

\[0=p_{b o t t o m}-p_{t o p}-\rho g \Delta z\]

or:

\[p_{t o p}-p_{b o t t o m}=-\rho g \Delta z\]

Ptop − Pbottom is a change in pressure, and Δz is the height of the volume element – a change in the distance above the ground. By saying these changes are infinitesimally small, the equation can be written in differential form, where dp is top pressure minus bottom pressure just as dz is top altitude minus bottom altitude.

\[d p=-\rho g d z\]

The result is the equation:

\[\frac{d p}{d z}=-\rho g\]

This equation is called the Hydrostatic Equation. See the video below (1:18) for further explanation:

Hydrostatic Equation

- Click here for transcript of the Hydrostatic Equation video.

-

Consider an air parcel at rest. There are three forces in balance, the downward pressure force, which is pressure times area in the parcel's top, and an upward pressure force on the parcel's bottom, and the downward force of gravity actually on the parcel's mass, which is just the acceleration due to gravity times the parcel's density times it's volume. The volume equals the parcel's cross sectional area times its height. We can sum these three forces together and set them equal to 0 since the parcel's at rest. Notice how the cross sectional area can be divided out. The next step is to put the pressure difference on the left hand side. And then shrink the air parcel height to be infinitesimally small, which makes the pressure difference infinitesimally small. By dividing both sides by the infinitesimally small height, we end up with an equation that's the derivative of the pressure with respect to height, which is equal to minus the parcel's density times gravity. This equation is the hydrostatic equation, which describes a change of atmospheric pressure with height.

Using the Ideal Gas Law, we can replace ρ and get the equation for dry air:

\[\frac{d p}{d z}=-g \frac{p}{R_{d} T} \quad\]

or

\[\quad \frac{d p}{p}=-\frac{g}{R_{d} T} d z=-\frac{M g}{R^{*} T} d z\]

We could integrate both sides to get the altitude dependence of p, but we can only do that if T is constant with height. It is not, but it does not vary by more than about ±20%. So, doing the integral,

\[p=p_{o} e^{-z / H} \quad\]

where \(p_{o}\) is the surface pressure and

\[H=\frac{R^{*} \overline{T}}{M_{\text {air}} g}\]

H is called a scale height because when z = H, we have p = poe–1. If we use an average T of 250 K, with Mair = 0.029 kg mol–1, then H = 7.2 km. The pressure at this height is about 360 hPa, close to the 300 mb surface that you have seen on the weather maps. Of course the forces are not always in hydrostatic balance and the pressure depends on temperature, thus the pressure changes from one location to another on a constant height surface.

From the hydrostatic equation, the atmospheric pressure falls off exponentially with height, which means that about every 7 km, the atmospheric pressure is about 1/3 less. At 40 km, the pressure is only a few tenths of a percent of the surface pressure. Similarly, the concentration of molecules is only a few tenths of a percent, and since molecules scatter sunlight, you can see in the picture below that the scattering is much greater near Earth's surface than it is high in the atmosphere.

Scattered light near Earth's surface. Credit: NASA