13.2: Folds

- Page ID

- 20181

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

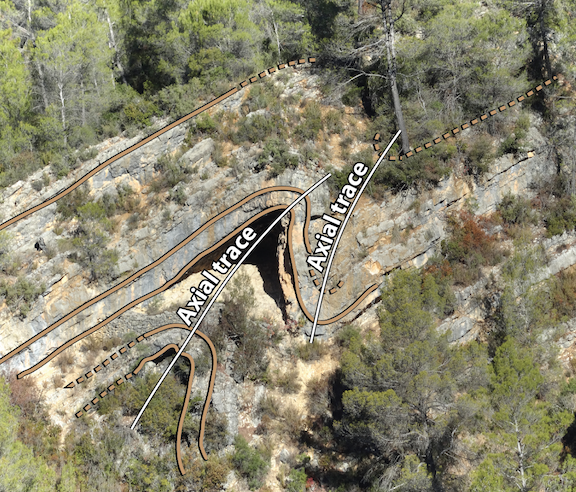

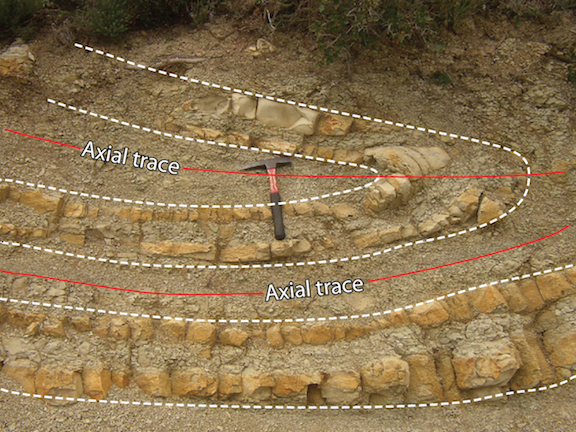

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Folds are a type of ductile deformation. They form when rocks bend in response to stress. The sides of a fold are its limbs (Figure 13.10). The limbs meet in a region of curvature called the hinge zone. A fold’s axial surface is an imaginary surface that runs along the hinge zone and cuts the fold in half. The line that forms when the axial surface intersects another surface, such as the top of a bed, is called the axial trace. Axial traces are sometimes marked on geological maps to show the location of the fold’s hinge zone.

Fold Classification

Synclines and Anticlines

Folds can be classified according to the whether the limbs slope toward or away from the hinge zone. If the limbs slope toward the hinge zone (i.e., the hinge zone points downward), as in the fold in the left of Figure 13.11, the fold is called a syncline. If the limbs slope away from the hinge zone (i.e., the hinge zone points upward), the fold is called an anticline. There is an anticline on the right side of Figure 13.11. The fold in Figure 13.10 is also an anticline. Sometimes an anticline or a syncline will occur by itself, but they can also occur in a series of alternating synclines and anticlines, similar to the way the anticline and syncline share a limb in Figure 13.11. A sequence of linked anticlines and synclines is called a fold train.

Symmetrical, Asymmetrical, Overturned, and Recumbent

In a symmetrical fold, the limbs slope at approximately the same angle on either side of the axial surface. The fold in Figure 13.10 is symmetrical. In an asymmetrical fold, the limbs slope at different angles on either side of the axial surface. The syncline in Figure 13.11 is asymmetrical. The limb on the left side of the syncline slopes toward the hinge at a steeper angle than the limb on the right.

If the fold is sufficiently tilted that the beds on one side have been tilted past vertical, and are sloping in the same direction, the fold is overturned (Figure 13.12).

It is possible for rocks to be folded so tightly that the fold limbs are nearly parallel. Folds with parallel limbs are called isoclinal folds. A recumbent fold is an isoclinal fold that has been overturned to the extent that the limbs are horizontal (Figure 13.13).

Folds in the Landscape

Folds can be of any size, and it’s very common to have smaller folds within larger folds (Figure 13.14). Large folds can extend over 10s of kilometres, and very small ones might only be visible under a microscope.

When folded rocks are weathered and eroded, they can alter the landscape by forming long ridges and valleys (Figure 13.15). Ridges and valleys curve into V-shapes if the hinge of the fold is not horizontal. A fold with a hinge that slopes downward is called a plunging fold (Figure 13.16).

Folds can create landforms, but anticlines are not necessarily expressed as ridges in the terrain. Likewise, synclines do not necessarily appear as valleys. When folded rocks erode, the landform that results depends how resistant individual layers are to erosion. For example, if the rocks in the interior of an anticline are more resistant to weathering than the surrounding rocks, a ridge will result (e.g., the low hill represented by units 4 and 5 in Figure 13.17, top). On the other hand, if rocks in the interior of the anticline are weaker, a valley will result (Figure 13.17, bottom, units d1 and d2). Similarly, a syncline with stronger rocks in the interior will weather to form a ridge, and a syncline with weaker rocks in the interior will weather to form a valley.

Practice with Types of Folds

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

References

Symonds, W. S. (1872). Records of the rocks; or, Notes on the geology, natural history, and antiquities of North & South Wales, Devon, & Cornwall. London: J. Murray Read the book