7.3: Classification of Igneous Rocks

- Page ID

- 20140

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Igneous rocks are classified (named) based on two sets of characteristics:

- The minerals they contain

- Their grain size and texture

Classification By Mineral Abundance

Igneous rocks can be divided into four categories based on their chemical composition: felsic, intermediate, mafic, and ultramafic. The diagram of Bowen’s reaction series (Figure 7.7) shows that differences in chemical composition correspond to differences in the types of minerals within an igneous rock. Igneous rock names are based in part on the minerals that igneous rocks contain, and on how abundant they are in a rock.

Figure 7.13 is a diagram with the minerals from Bowen’s reaction series, and it’s used to decide which name to give an igneous rock. First, notice that the diagram has rows with different kinds of information, but is also organized in columns according to the four compositional categories. The top box shows the range of mineral proportions for each compositional category. An igneous rock can be represented as a vertical line drawn through the top box of the diagram, and the vertical scale—with the distance between each tick mark representing 10% of the minerals within a rock by volume—is used to break down the proportion of each mineral it contains.

Consider the arrows in the mafic field of the diagram. They represent a rock containing 60% pyroxene and 40% pyroxene. An igneous rock at the boundary between the mafic and ultramafic fields (marked with a vertical dashed line) would have approximately 20% olivine, 60% pyroxene, and 20% Ca-rich plagioclase feldspar by volume.

Classification By Grain Size

The lower two boxes of the diagram contain igneous rock names, and you’ll notice that there are two igneous rock names for each compositional category. So which name do you use?

The name to choose depends on whether the igneous rock cooled within Earth (whether it’s an intrusive or plutonic igneous rock), or whether it cooled on the Earth’s surface after erupting from a volcano (making it an extrusive or volcanic igneous rock).

What this means is that two igneous rocks comprised of exactly the same minerals, and in the exactly the same proportions, can have different names. A felsic intrusive rock is called granite, whereas a felsic extrusive rock is called rhyolite. Granite and rhyolite have the same mineral composition, but their grain size gives each a distinct appearance. A rock of intermediate composition is diorite if it’s course-grained, and andesite if it’s fine-grained. A mafic rock is gabbro if it’s course-grained, and basalt if fine-grained. The course-grained version of an ultramafic rock is peridotite, and the fine-grained version is komatiite. It makes sense to use different names because rocks of different grain sizes form in different ways and in different geological settings.

Try It Out!

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What Determines Grain Size?

The key difference between intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks—the size of crystals making them up—is related to how rapidly melted rock cools. The longer melted rock has to cool, the larger the crystals within it can become. Magma cools much slower within Earth than on Earth’s surface because magma within Earth is insulated by surrounding rock. Notice that in Figure 7.13, the intrusive rocks have crystals large enough that you can see individual crystals—either by identifying their boundaries, or seeing light reflecting from a crystal face. A rock with individual crystals that are visible to the unaided eye has a phaneritic or coarse-grained texture. The extrusive rocks have much smaller crystals. The crystals are so small that the bulk of individual crystals cannot be distinguished, and the rock may look like a dull mass. A rock with crystals that are too small to see with the unaided eye has an aphanitic or fine-grained texture. Table 7.1 summarizes the key differences between intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks.

| Table 7.1 Comparison of Intrusive and Extrusive Igneous Rocks | ||

| Magma cools within Earth | Lava cools on Earth’s surface | |

| Terminology | Intrusive/ plutonic | Extrusive/ volcanic |

| Cooling rate | Slow: surrounding rocks insulate the magma chamber. | Rapid: heat is exchanged with the atmosphere. |

| Texture | Phaneritic (coarse-grained): individual crystals are large enough to see without magnification. | Aphanitic (fine-grained): crystals are too small to see without magnification. |

Practice with Igneous Rock Names

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Does This Mean an Igneous Rock Can Only Have One Grain Size?

No. Something interesting happens when there is a change in the rate at which melted rock is cooling. If magma is cooling in a magma chamber, some minerals will begin to crystallize before others do. If cooling is slow enough, those crystals can become quite large.

Now imagine the magma is suddenly heaved out of the magma chamber and erupted from a volcano. The larger crystals will flow out with the lava. The lava will then cool rapidly, and the larger crystals will be surrounded by much smaller ones. An igneous rock with crystals of distinctly different size (Figure 7.14) is said to have a porphyritic texture, or might be referred to as a porphyry. The larger crystals are called phenocrysts, and the smaller ones are referred to as the groundmass.

Which Phenocrysts Will Form?

Query \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Classifying Igneous Rocks According to the Proportion of Dark Minerals

If you’re unsure of which minerals are present in an intrusive igneous rock, there’s is a quick way to approximate the composition of that rock. In general, igneous rocks have an increasing proportion of dark minerals as they become more mafic (Figure 7.16).

The dark-colored minerals are those higher in iron and magnesium (e.g., olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, biotite), and for that reason they’re sometimes referred to collectively as ferromagnesian minerals. By estimating the proportion of light minerals to dark minerals in a sample, it is possible to place that sample in Figure 7.16. Graphical scales are used to help visualize the proportions of light and dark minerals (Figure 7.17).

It’s important to note that estimating the proportion of dark minerals is only approximate as a means for identifying igneous rocks. One problem is that plagioclase feldspar is light-colored when it’s sodium-rich, but can appear darker if it’s calcium-rich. Plagioclase feldspar is not ferromagnesian, so it falls in the non-ferromagnesian (light minerals) region in Figure 7.16 even when it’s dark.

Try It Out!

Query \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Classifying Igneous Rocks When Individual Crystals Are Not Visible

The method of estimating the percentage of minerals works well for phaneritic igneous rocks, in which individual crystals are visible with little to no magnification. If an igneous rock is porphyritic but otherwise aphanitic (e.g., Figure 7.14), the minerals present as phenocrysts give clues to the identity of the rock. However, there are cases where mineral composition can’t be determined by looking at visible crystals. These include volcanic rocks without phenocrysts, and glassy igneous rocks.

Volcanic Rocks Without Phenocrysts

In the absence of visible crystals or phenocrysts, volcanic rocks are be classified on the basis of color and other textural features. As you may have noticed in Figure 7.13, the color of volcanic rocks goes from light to dark as the composition goes from felsic to mafic. Rhyolite is often a tan or pinkish color, andesite is often grey, and basalt ranges from brown to dark green to black (Figure 7.19).

Basalt often shows textural features related to lava freezing around gas bubbles. When magma is underground, pressure keeps gases dissolved, but once magma has erupted, the pressure is much lower. Gases dissolved in the lava are released, and bubbles can develop. When lava freezes around the bubbles, vesicles are formed (circular inset in 7.19). If the vesicles are later filled by other minerals, the filled vesicles are called amygdules (box inset in Figure 7.19).

Glassy Volcanic Rocks

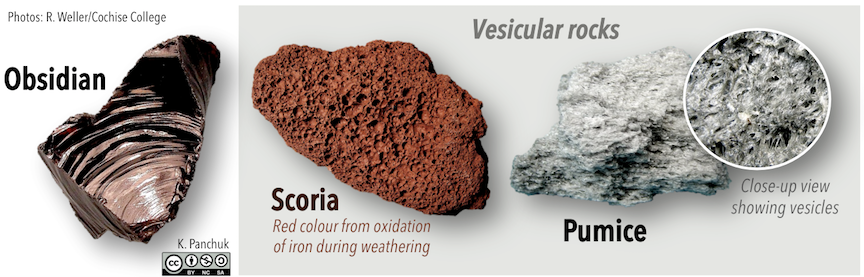

Crystal size depends on cooling rate. The faster magma or lava cools, the smaller the crystals it contains. It’s possible for lava to cool so rapidly that no crystals can form. The result is volcanic glass. Volcanic glass can be smooth like obsidian or vesicular like scoria (mafic) and pumice (felsic; Figure 7.20). Pumice can float on water because of its low-density felsic composition and enclosed vesicles.

Practice with Textures

Query \(\PageIndex{5}\)

How did you do with those flashcards? If you’re confident you know those terms, give this next exercise a try.

Query \(\PageIndex{6}\)