14.5.2: Spinels and other Oxides with Mixed Coordination

- Page ID

- 18661

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Inverse Spinels

spinel MgAl2O4

magnetite Fe3O4

Normal Spinels

chromite FeCr2O4

franklinite ZnFe2O4

Other Oxides

perovskite CaTiO3

chrysoberyl BeAl2O4

uraninite UO2

thorianite ThO2

cuprite Cu2O

In minerals of the spinel group, both tetrahedral and octahedral sites are occupied by metal ions. In what we call normal spinels, each metal species is found in either tetrahedral or octahedral coordination but not both. We can write the formula of normal spinels as XY2O4, with X representing the tetrahedral cation and Y the octahedral cation. In inverse spinels, one metal species occupies both coordinations. A general formula is Y[XY]O4, with the brackets identifying the two different metal ions in octahedral sites.

Mineralogists have identified other oxides that do not fit into the tetrahedral, octahedral, or spinel groups. In uraninite and thorianite, for example, metal atoms occupy cubic sites. In perovskite, Ti and Ca are in 6-fold and 12-fold coordinations, respectively. In cuprite, Cu is in 2-fold coordination; and chrysoberyl is isostructural with olivine.

For more general information about oxides, see Chapter 9: Ore Deposi

Spinel MgAl2O4

Origin of Name

From the Latin word spina, meaning “thorn,” a reference to the sharp crystals.

Hand Specimen Identification

The term spinel is used in a generic sense to describe any of the many minerals with spinel structure. The term also refers to a specific mineral with composition MgAl2O4. This mineral is recognized by its octahedral crystals, hardness (H = 8), and vitreous luster. Spinel comes in many different colors, but the red color seen in Figure 14.337 is most common and most diagnostic.

Physical Properties

| hardness | 8 |

| specific gravity | 3.5 to 4.0 |

| cleavage/fracture | none/conchoidal |

| luster/transparency | vitreous/transparent to translucent |

| color | variable, red, lavender, blue, green, brown, white, or black |

| streak | white |

Properties in Thin Section

Nearly pure MgAl2O4 spinel is colorless in thin section but is pleochroic green or blue-green if Fe substitutes for Mg. Octahedral shape and high index of refraction aid identification. Isotropic, n = 1.74.

Crystallography

Spinel is cubic, a = 8.09, Z = 8; space group \(F\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Spinel typically forms octahedral crystals; twinning and modifying faces are common. Massive forms and irregular grains are also known.

Structure and Composition

Spinel minerals have relatively simple cubic structures. MgO6 octahedra and AlO4 tetrahedra share edges and are closest packed. Fe, Zn, and Mn may substitute for Mg. Fe and Cr may substitute for Al.

Occurrence and Associations

Spinel is a high-temperature mineral found in metamorphosed carbonates or schists, as an accessory in mafic igneous rocks, and in placers. Associated minerals include calcite, dolomite, garnet, and Ca-Mg silicates in marbles; garnet, corundum, sillimanite, andalusite and cordierite in highly aluminous rocks; diopside, olivine, chondrodite, in mafic rocks; and other dense minerals in placers.

Varieties

Pleonaste is the name given to intermediate Fe-Mg spinels. Ruby spinel is the name of gemmy-red spinel; various other gem names are used to a lesser extent.

Related Minerals

Spinel is isostructural with other members of the spinel group and with bornhardite, Co3Se4; linnaeite, Co2S4; polydymite, Ni3S4; indite, FeIn2S4; and greigite, Fe3S4. Spinel forms solid solutions with other members of the spinel group, including hercynite, FeAl2O4; gahnite, ZnAl2O4; galaxite, MnAl2O4; zincochromite, ZnCr2O4; and magnesiochromite, MgCr2O4.

Magnetite Fe3O4

Origin of Name

Named after Magnesia, near Macedonia in Thessaly, where the Greeks found this mineral.

Hand Specimen Identification

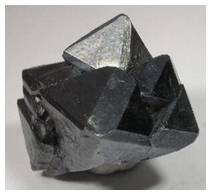

Magnetite, a member of the spinel group, is similar to other dense, hard, dark-colored minerals. It is, however, characterized by its strong magnetism, which distinguishes it from ilmenite, chromite, and other similar looking minerals (Figure 14.338). Macroscopic euhedral crystals are uncommon, but form octahedra (Figure 14.339).

Physical Properties

| hardness | 6 |

| specific gravity | 5.20 |

| cleavage/fracture | none/subconchoidal |

| luster/transparency | metallic/opaque |

| color | black |

| streak | black |

Crystallography

Magnetite is a cubic mineral, a = 8.397, Z = 8; space group \(F\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Magnetite crystals are octahedra that sometimes display contact or lamellar twins. Magnetite is also common as massive or granular aggregates or disseminated as fine grains.

Structure and Composition

Magnetite has the spinel structure (see spinel structure, above). Some Ti is usually present in magnetite; at high temperature a complete solid solution to Fe2TiO4 (ulvöspinel) is possible. Minor amounts of Mg, Mn, Ni, Al, Cr, and V may substitute for Fe.

Occurrence and Associations

Magnetite is common and widespread. It is found as an accessory in many types of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks and in unconsolidated sediments. It may be concentrated to form ore bodies by magmatic, metamorphic, or sedimentary processes.

Related Minerals

Magnetite forms solid solutions with ulvöspinel, Fe2TiO4; magnesioferrite, MgFe2O4; jacobsite, MnFe2O4; and to a lesser extent with maghemite, Fe2O3.

Chromite FeCr2O4

Origin of Name

The name chromite refers to this mineral’s composition.

Hand Specimen Identification

Black color, high density, black/brown streak, metallic luster, and association distinguish chromite. It may be slightly magnetic and is sometimes confused with magnetite or ilmenite. The photos in these two photos show typical examples.

Physical Properties

| hardness | 5.5 |

| specific gravity | 4.5-4.8 |

| cleavage/fracture | none/conchoidal |

| luster/transparency | metallic/subtranslucent; opaque |

| color | black, brownish black |

| streak | brown, dark brown |

Crystallography

Chromite is a cubic mineral, a = 8.37, Z = 8; space group \(F\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Rare euhedral crystals are octahedral; chromite is generally massive or granular.

Structure and Composition

The structure of chromite is the same as that of all the spinel minerals (see spinel structure). Mg, Fe, Al, and Zn are typical impurities.

Occurrence and Associations

Primary chromite is found with olivine, pyroxene, spinel, magnetite, and sulfides in ultramafic rocks. It is also found in placers and black sands. Chromite is commonly a minor accessory mineral but may be concentrated by gravity or magmatic processes.

Related Minerals

Chromite has one polymorph, donathite. Chromite forms solid solutions with magnesiochromite, MgCr2O4, and hercynite, FeAl2O4, and to lesser extent with other spinel minerals.

Franklinite ZnFe2O4

Origin of Name

Named after Franklin, New Jersey, the type locality where this mineral is found.

Physical Properties

| hardness | 6 |

| specific gravity | 5.32 |

| cleavage/fracture | none/conchoidal |

| luster/transparency | metallic/opaque |

| color | black or iron-black |

| streak | black, reddish brown to dark brown |

Crystallography

Franklinite is cubic, a = 8.43, Z = 8; space group \(F\dfrac{4}{d}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{4}{m}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Octahedral franklinite crystals, often with modifying faces, are common in Franklin, New Jersey, the only place where this mineral is found in large quantities. Franklinite also occurs as discrete rounded grains, as granular masses, or in massive lenses.

Structure and Composition

Franklinite‘s structure is the same as that of other spinel minerals (see spinel structure). Franklinite normally contains substantial Mn substituting for Zn. Mn may also substitute for Fe. Minor Mg, Cr, and V also may be present.

Occurrence and Associations

Franklinite is associated with zincite and willemite, two other zinc minerals, in zinc ore deposits at Franklin, New Jersey. The host rock is a coarse-grained limestone.

Related Minerals

Franklinite is similar in many ways to other dark-colored spinel minerals. It forms minor solid solutions with most of them.

Chrysoberyl BeAl2O4

Origin of Name

From the Greek words meaning “golden beryl.”

Hand Specimen Identification

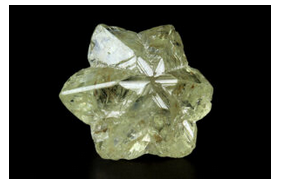

Translucent to transparent character, light color, vitreous luster, extreme hardness (H = 8.5), and common twinning characterize chrysoberyl. Chrysoberyl looks superficially like any of a number of other light-colored translucent/transparent minerals, but is significantly harder than most. Greenish to yellow colors are typical, like the specimens in these two figures, but other hues are known.

When visible, chrysoberyl‘s orthorhombic symmetry helps identify chrysoberyl. Cyclic twinning, such as seen in Figure 14.344, is classic for this mineral.

Physical Properties

| hardness | 8.5 |

| specific gravity | 3.7 to 3.8 |

| cleavage/fracture | good but indistinct prismatic {011}, poor (010)/ subconchoidal |

| luster/transparency | vitreous/transparent to translucent |

| color | yellow, green, or brown |

| streak | white |

Properties in Thin Section

Chrysoberyl is biaxial (+), α = 1.747 , β = 1.748, γ = 1.757, δ = 0.010, 2V = 45°.

Crystallography

Chrysoberyl is orthorhombic, a = 4.24, b = 9.39, c = 5.47, Z = 4; space group \(P\dfrac{2_1}{b}\dfrac{2_1}{n}\dfrac{2_1}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{2}{m}\dfrac{2}{}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Chrysoberyl is generally tabular and sometimes heart shaped or pseudohexagonal due to cyclic twinning. Faces are often striated.

Structure and Composition

Chrysoberyl‘s structure, similar to that of olivine, contains hexagonal closest packed oxygens with Be in tetrahedral sites and Al in octahedral sites.

Occurrence and Associations

Chrysoberyl is a rare mineral occurring in granites, pegmatites, mica schists, and some placers.

Varieties

Cat’s eye (cymophane) is a green chatoyant gem variety of chrysoberyl. Alexandrite is an emerald-green gem variety that appears red under artificial light. Both are very valuable.

Related Minerals

Chrysoberyl is isostructural with olivine minerals. It is chemically similar to members of the spinel group but has a different structure.

Uraninite UO2

Origin of Name

The name uraninite refers to this mineral’s composition.

Hand Specimen Identification

Uraninite is characterized by its radioactivity, association with other radioactive minerals, high specific gravity, brown to black streak, black color, and luster. It can be confused with other dense, dark-colored minerals.

Figure 14.345 shows a typical nondescript sample of uraninite. In contrast, Figure 14.346 show a spectacular euhedral crystal cluster. Figure 14.347 is a photo of botryoidal uraninite. Each of the spheres grew outward from seeds at their centers and subsequently grew together to produce the cluster seen.

Physical Properties

| hardness | 5.5 |

| specific gravity | 7 to 9.5 |

| cleavage/fracture | none/conchoidal |

| luster/transparency | pitchy dull to submetallic/opaque |

| color | black |

| streak | brown to black |

Crystallography

Uraninite is cubic, a = 5.4682, Z = 4; space group \(F\dfrac{4}{m}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{4}{m}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Individual crystals of uraninite are rare but may form cubes, octahedra, or combinations. Massive, colloform, or botryoidal forms are more typical.

Structure and Composition

Uraninite is isostructural with fluorite (see fluorite structure, above). Uraninite is isostructural with thorianite, ThO2; cerianite, (Ce,Th)O2; and fluorite (CaF2). It is closely related to sellaite, MgF2, and frankdicksonite, BaF2.U valence and U:O ratios are somewhat variable; uraninite is really a mixture of UO2 and U3O8. Th may substitute for U; N, Ar, Fe, Ca, Zr, and rare earths are also commonly present. Pb and Ra are always present as radioactive decay products.

Occurrence and Associations

Uraninite occurs in granitic pegmatites, in veins, and in sandstones. Associated minerals include quartz, K-feldspar, zircon, tourmaline, and monazite in pegmatites; cassiterite, galena, sulfides, and arsenides in veins; and quartz and various other secondary minerals in sandstones. Uraninite also concentrates in coal and other organic debris in sediments and related sedimentary rocks.

Varieties

Massive forms of uraninite are called pitchblende.

Related Minerals

Uraninite is isostructural with fluorite, CaF2, and cerianite, (Ce,Th)O2. It forms complete solid solution with thorianite, ThO2. Other related minerals include baddeleyite, ZrO2.

Cuprite Cu2O

Origin of Name

From the Latin word cuprum, meaning “copper.”

Hand Specimen Identification

Red- or black-colored crystals, sometime showing internal reflection, octahedral crystal shape, adamantine luster, brownish red streak, and association all help identify cuprite. It may be confused with cassiterite, hematite, and cinnabar, all red minerals. It can sometimes also be confused with rutile and other red-black oxides but is denser than most of them. Figures 14.348 and 14.349 show two examples of cuprite crystals.

Physical Properties

| hardness | 3.5 to 4 |

| specific gravity | 6.14 |

| cleavage/fracture | imperfect {111}/conchoidal |

| luster/transparency | adamantine, submetallic or earthy/often translucent to transparent |

| color | dark red, sometimes almost black |

| streak | brownish red, metallic |

Crystallography

Cuprite is cubic, a = 4.27, Z = 2; space group \(F\dfrac{4}{m}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\); point group \(\dfrac{4}{m}\overline{3}\dfrac{2}{m}\).

Habit

Octahedral, cubic, and dodecahedral forms, often in combination, are common. Cuprite may occur as elongated capillary crystals called chalcotrichite.

Structure and Composition

Oxygen, in tetrahedral groups, is arranged in a body centered cubic array. Each Cu is bonded to two O. Cuprite is generally close to end-member composition; Fe is a common minor impurity.

Occurrence and Associations

Cuprite is a secondary mineral found in the oxidized zones of copper deposits. Native copper, limonite, and secondary copper minerals such as malachite, azurite, and chrysocolla are typically associated minerals.

Related Minerals

Tenorite, CuO, is similar in composition and occurrence.