8.3.7: Nonfoliated Metamorphic Rocks

- Page ID

- 18616

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

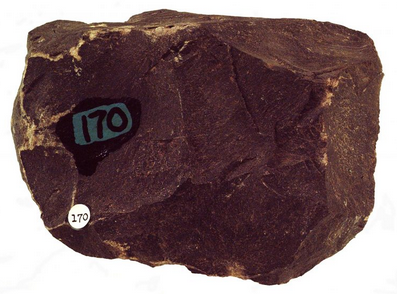

Some metamorphic rocks are fine-grained and lack metamorphic fabrics. For example, hornfels are dark colored fine-grained rocks lacking both lineation and foliation. Many hornfels form at low pressure from contact metamorphism of a mudstone or shale. These rocks may contain no visible layering or fractures and appear as a homogeneous mass. Most hornfels are quite hard and durable because constituent grains are tightly bound together. Figure 8.33 shows an example of biotite hornfels, the most common kind of hornfels. These rocks are dark brown and sometimes have a slight sheen due to microscopic grains of biotite. Other hornfels may have different colors; the color depends on the minerals present. Some hornfels contain grains that become visible after weathering (because different minerals weather in different ways) but, because of the generally uniform rock color, are invisible otherwise.

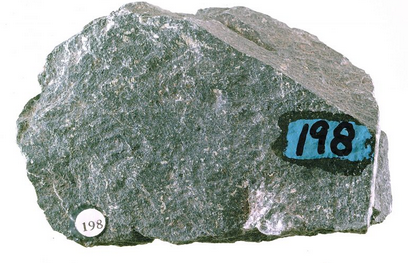

Greenstones, which are a specific kind of hornfels, form by metamorphism of basalts. Figure 8.34 shows a 9-cm wide sample of greenstone from Ely, Minnesota. The greenish color is due to chlorite or epidote that grew during metamorphism. Figure 8.35 shows an outcrop of greenstone in Italy. The rock originated as an ocean-floor basalt, and contains rounded structures called pillows, indicative of submarine eruption.

Many nonfoliated metamorphic rocks are dominated by a single mineral. In these rocks, individual mineral grains or crystals, which may start small, recrystallize (grow together) during metamorphism to produce larger crystals. Figure 8.36, for example, shows an 8-cm wide rock consisting only of coarse blue calcite. This rock had a limestone protolith. Petrologists use the term marble for all metamorphic carbonate rocks – rocks that form from limestone or dolostone – dominated by calcite or dolomite. (This sometimes leads to confusion because builders and others use the same word to describe any polished slab of rock.)

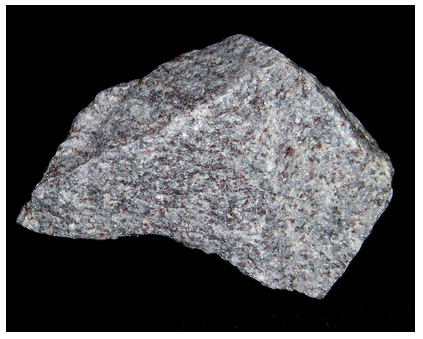

Quartzite, also a common nonfoliated metamorphic rock, forms by metamorphism of sandstone. Most sandstones comprise mainly quartz and so do quartzites. Figure 8.37 shows a typical example. It consists of small quartz crystals that have grown together so that no grain boundaries are visible without a microscope. The recrystallization produced a typical hard and shiny quartzite (sometimes described as frosty), and during metamorphism any original sedimentary textures were erased. Common quartzites are white or gray, but minor components may add color. The pink color in this sample comes from hematite that may have been part of the cement that held the sandstone together. If the protolith sandstone contained minerals besides quartz, so too will the product quartzite. Thus, feldspar, titanite, rutile, magnetite, or zircon may be present in small amounts. And, if the protolith contained some clay, micas and other aluminous minerals may be present.

This figure (8.38) shows an example of a garnet granulite. Many granulites are foliated, but this one is not. Granulites form at the highest grades of metamorphism and can form from many sorts of protoliths. This rock contains black biotite, light-colored K-feldspar and many conspicuous red garnets. The abundant biotite and garnet tell us that the rock is aluminum-rich, suggesting it has a sedimentary origin. Figure 8.10 shows a different granulite; it contains hornblende and plagioclase besides large garnets. The garnet porphyroblasts in Figure 8.10 are 1-2 cm wide. The garnets in this granulite are only a few millimeters wide at most.