9.3: Volcanic Eruptions

- Page ID

- 2537

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)INTRODUCTION

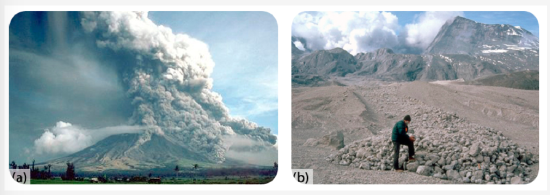

In 1980, Mount St. Helens blew up in the costliest and deadliest volcanic eruption in United States history. The eruption killed 57 people, destroyed 250 homes and swept away 47 bridges (figure 1).

Mt. St. Helens still has minor earthquakes and eruptions. The volcano now has a horseshoe-shaped crater with a lava dome inside. The dome is formed of viscous lava that oozes into place.

MAGMA COMPOSITION

Volcanoes do not always erupt in the same way. Each volcanic eruption is unique, differing in size, style, and composition of erupted material. One key to what makes the eruption unique is the chemical composition of the magma that feeds a volcano, which determines (1) the eruption style, (2) the type of volcanic cone that forms, and (3) the composition of rocks that are found at the volcano.

Remember from the Rocks chapter that different minerals within a rock melt at different temperatures. The amount of partial melting and the composition of the original rock determine the composition of the magma. Magma collects in magma chambers in the crust at 160 kilometers (100 miles) beneath the surface.

The words that describe composition of igneous rocks also describe magma composition.

- Mafic magmas are low in silica and contain more dark, magnesium and iron rich mafic minerals, such as olivine and pyroxene.

- Felsic magmas are higher in silica and contain lighter colored minerals such as quartz and orthoclase feldspar. The higher the amount of silica in the magma, the higher is its viscosity. Viscosity is a liquid’s resistance to flow (figure 2).

Viscosity determines what the magma will do. Mafic magma is not viscous and will flow easily to the surface. Felsic magma is viscous and does not flow easily. Most felsic magma will stay deeper in the crust and will cool to form igneous intrusive rocks such as granite and granodiorite. If felsic magma rises into a magma chamber, it may be too viscous to move and so it gets stuck. Dissolved gases become trapped by thick magma. The magma churns in the chamber and the pressure builds.

ERUPTIONS

The type of magma in the chamber determines the type of volcanic eruption. Although the two major kinds of eruptions—explosive and effusive—are described in this section, there is an entire continuum of eruption types. Which magma composition do you think leads to each type?

Explosive Eruptions

A large explosive eruption creates even more devastation than the force of the atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki at the end of World War II in which more than 40,000 people died. A large explosive volcanic eruption is 10,000 times as powerful. Felsic magmas erupt explosively. Hot, gas-rich magma churns within the chamber. The pressure becomes so great that the magma eventually breaks the seal and explodes, just like when a cork is released from a bottle of champagne. Magma, rock, and ash burst upward in an enormous explosion. The erupted material is called tephra (figure 3).

Scorching hot tephra, ash, and gas may speed down the volcano’s slopes at 700 km/h (450 mph) as a pyroclastic flow. Pyroclastic flows knock down everything in their path. The temperature inside a pyroclastic flow may be as high as 1,000°C (1,800°F) (figure 4).

Watch this video of a pyroclastic flow at Montserrat volcano.

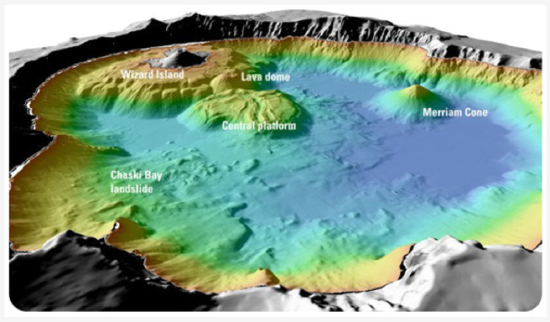

Prior to the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980, the Lassen Peak eruption on May 22, 1915, was the most recent Cascades eruption. A column of ash and gas shot 30,000 feet into the air. This triggered a high-speed pyroclastic flow, which melted snow and created a volcanic mudflow known as a lahar. Lassen Peak currently has geothermal activity and could erupt explosively again. Mt. Shasta, the other active volcano in California, erupts every 600 to 800 years. An eruption would most likely create a large pyroclastic flow, and probably a lahar. Of course, Mt. Shasta could explode and collapse like Mt. Mazama in Oregon (figure 5).

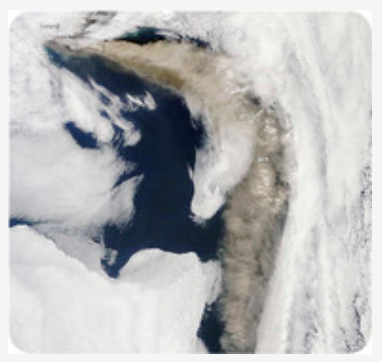

Volcanic gases can form poisonous and invisible clouds in the atmosphere. These gases may contribute to environmental problems such as acid rain and ozone destruction. Particles of dust and ash may stay in the atmosphere for years, disrupting weather patterns and blocking sunlight (figure 6).

Effusive Eruptions

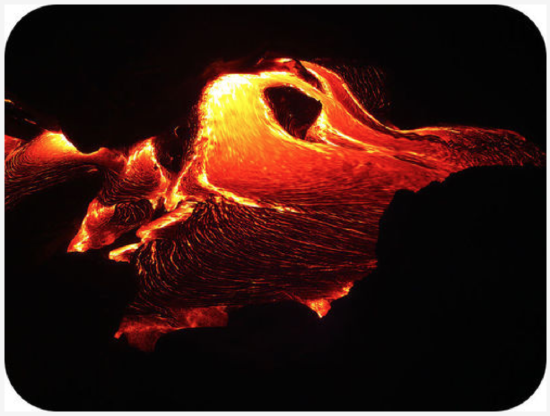

Mafic magma creates gentler effusive eruptions. Although the pressure builds enough for the magma to erupt, it does not erupt with the same explosive force as felsic magma. People can usually be evacuated before an effusive eruption, so they are much less deadly. Magma pushes toward the surface through fissures. Eventually, the magma reaches the surface and erupts through a vent (figure 7).

- The Kilauea volcanic eruption in 2008 is seen in this short video.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BtH79yxBIJI - Watch this movie with thermal camera of a lava stream within the vent of a Hawaiian volcano.

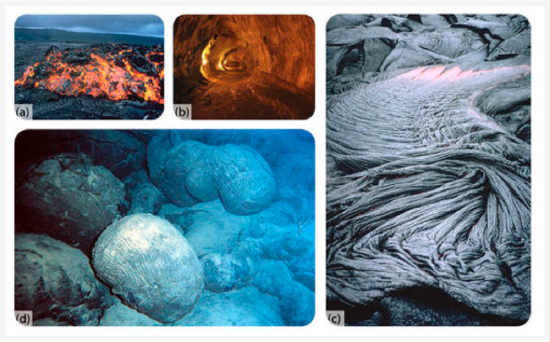

Low-viscosity lava flows down mountainsides. Differences in composition and where the lavas erupt result in three types of lava flow coming from effusive eruptions (figure 8).

- Watch this videos of an undersea eruption. In this video you can hear the underwater eruption as well.

Although effusive eruptions rarely kill anyone, they can be destructive. Even when people know that a lava flow is approaching, there is not much anyone can do to stop it from destroying a building or road (figure 9).

PREDICTING VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS

Volcanologists attempt to forecast volcanic eruptions, but this has proven to be nearly as difficult as predicting an earthquake. Many pieces of evidence can mean that a volcano is about to erupt, but the time and magnitude of the eruption are difficult to pin down. This evidence includes the history of previous volcanic activity, earthquakes, slope deformation, and gas emissions.

History of Volcanic Activity

A volcano’s history—how long since its last eruption and the time span between its previous eruptions—is a good first step to predicting eruptions. Which of these categories does the volcano fit into?

- Active: currently erupting or showing signs of erupting soon.

- Dormant: no current activity, but has erupted recently (figure 10).

- Extinct: no activity for some time; will probably not erupt again.

Active and dormant volcanoes are heavily monitored, especially in populated areas.

Earthquakes

Moving magma shakes the ground, so the number and size of earthquakes increases before an eruption. A volcano that is about to erupt may produce a sequence of earthquakes. Scientists use seismographs that record the length and strength of each earthquake to try to determine if an eruption is imminent.

Slope Deformation

Magma and gas can push the volcano’s slope upward. Most ground deformation is subtle and can only be detected by tiltmeters, which are instruments that measure the angle of the slope of a volcano. But ground swelling may sometimes create huge changes in the shape of a volcano. Mount St. Helens grew a bulge on its north side before its 1980 eruption. Ground swelling may also increase rock falls and landslides.

Gas Emissions

Gases may be able to escape a volcano before magma reaches the surface. Scientists measure gas emissions in vents on or around the volcano. Gases, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrochloric acid (HCl), and even water vapor can be measured at the site (figure 11) or, in some cases, from a distance using satellites. The amounts of gases and their ratios are calculated to help predict eruptions.

Remote Monitoring

Some gases can be monitored using satellite technology (figure 12). Satellites also monitor temperature readings and deformation. As technology improves, scientists are better able to detect changes in a volcano accurately and safely.

Since volcanologists are usually uncertain about an eruption, officials may not know whether to require an evacuation. If people are evacuated and the eruption doesn’t happen, the people will be displeased and less likely to evacuate the next time there is a threat of an eruption. The costs of disrupting business are great. However, scientists continue to work to improve the accuracy of their predictions.

LESSON SUMMARY

- The style of a volcanic eruption depends on magma viscosity.

- Felsic magmas produce explosive eruptions. Mafic magmas produce effusive eruptions.

- Explosive eruptions happen along the edges of continents and produce tremendous amounts of material ejected into the air.

- Non-explosive eruptions produce lavas, such as a’a, pahoehoe, and pillow lavas.

- Volcanoes are classified as active, dormant, or extinct.

- Signs that a volcano may soon erupt include earthquakes, surface bulging, and gases emitted, as well as other changes that can be monitored by scientists.

Visit this USGS photo glossary to broaden your knowledge.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What skill does this content help you develop?

- What are the key topics covered in this content?

- How can the content in this section help you demonstrate mastery of a specific skill?

- What questions do you have about this content?

Contributors and Attributions

Original content from Kimberly Schulte (Columbia Basin College) and supplemented by Lumen Learning. The content on this page is copyrighted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.