4.2: The 1811-1812 New Madrid Earthquakes

- Page ID

- 7005

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Rumbling on the Reelfoot Fault

Credit: Nuttli, 1973.

Video: Isoseismal Maps Explained (3:03)

Isoseismal Maps Explained

- Click here for the transcript of Isoseismal Maps Explained.

-

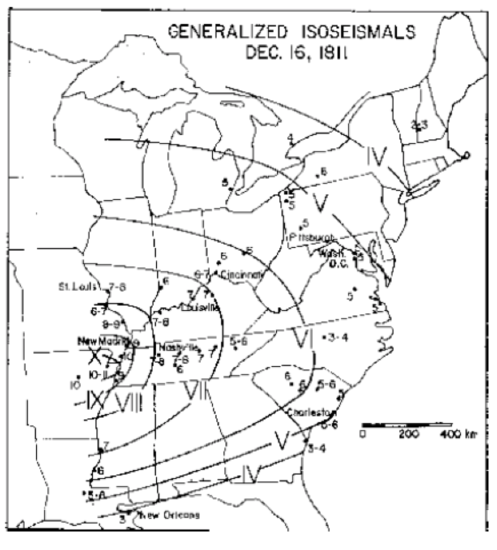

PRESENTER: This is an isoseismal map from Otto Nuttli's paper about the 1811-1812 sequence of three earthquakes that happened in New Madrid. An isoseismal map is one in which similarly felt seismic intensities are contoured so that you can see how far away different intensities of shaking were felt from the epicenter of the earthquake. It helps you figure out where the epicenter probably was, and it helps you figure out what the magnitude probably was. So these kinds of maps are normally used when we don't have the instrumentation to actually have determined where the epicenter was or the magnitude with a seismometer.

In this case, the way Nuttli made this map is that he combed through old newspaper accounts of eyewitness reports of felt shaking from this earthquake, and then he put those on a scale of one to 12, one being hardly felt it at all or not at all, and 12 being absolute destruction, hell on Earth. So for example, near New Madrid, where the epicenter was, there are some reports of 10 to 11. Far away in New England, this earthquake was felt but at a much smaller intensity, so there's an intensity of two or three. Then after you collect a lot of this data and put it on a map, you can try to connect up similar intensities and, basically, you end up drawing rings of intensity around your epicenter.

So here is the contour for intensity 10, say. Out here is the contour that separates the fours from threes, and so on. One thing to notice from this map is that there weren't a lot of people west of the Mississippi, so all the rings kind of die out here at the Mississippi. That's the best we can do. These maps are actually still used today, but they're usually used for ground truthing, as best we can, historic earthquakes. For example, when the magnitude 5.8 earthquake happened in August of 2011, you could have logged into the USGS site, told them your zip code, told them how much shaking you thought you felt, and then they compiled the map. And this is the map they compiled that shows how much shaking there were in different places around the country.

So the folks in Richmond felt very strong shaking between intensity six and seven, estimated. And up into Canada, people felt this earthquake too. So of course, we know the actual magnitude in this earthquake because we have instrumentation now. We can calculate it. So what this is useful for is to take a map like this and, if you know you have historic earthquakes in this area, you can try to figure out how far away people felt that and then guess about what magnitude it probably was compared to where people felt it today where we do know what the magnitude was. So when you read Nuttli's paper, keep in mind how these isoseismal maps are made and how much detective work it takes to actually do this.Credit: Dutton

Please read this article describing the 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquake sequence, then proceed with the rest of the lesson.

Reading assignment

Nuttli, O. W. (1973). The Mississippi Valley Earthquakes of 1811 and 1812: Intensities, Ground Motion, and Magnitudes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 63(1), 227–248.

This paper was written by Otto Nuttli, a seismologist at Saint Louis University. He looked at many historical accounts of the 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquake sequence in order to describe the physics of these events with as much accuracy as possible. This is a technical paper, intended for an audience of other seismologists. I don't expect you to digest every detail of Nuttli's analysis.

Read these sections and their included figures: Abstract, Introduction, Intensity data, Discussion, Reflections.

Skim the following sections: Relations between intensity and ground motion, Magnitudes and ground motion of the 1811–1812 earthquakes, Appendix.

When you read this article try to answer or at least think about the following:- Why don't we know the exact magnitudes of these earthquakes?

- How many earthquakes were there?

- Where is the New Madrid Seismic Zone?

- Different magnitude scales are mentioned, such as MM, Ms, and Mb. What are these? Do you know how each one is measured?

- What's an isoseismal map?

- What is attenuation? What is important about attenuation with regard to these earthquakes?

Tell us about it!

What other questions do you have after reading this article? Post to the Questions discussion.