8.1.2: Threats to Biodiversity

- Page ID

- 11778

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

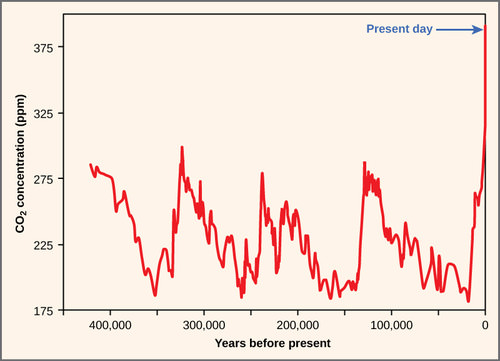

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The core threat to biodiversity on the planet, and therefore a threat to human welfare, is the combination of human population growth and the resources used by that population. The human population requires resources to survive and grow, and those resources are being removed unsustainably from the environment. The three greatest proximate threats to biodiversity are habitat loss, overharvesting, and introduction of exotic species. The first two of these are a direct result of human population growth and resource use. The third results from increased mobility and trade. A fourth major cause of extinction, anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change, has not yet had a large impact, but it is predicted to become significant during this century. Global climate change is also a consequence of human population needs for energy and the use of fossil fuels to meet those needs (Figure below). Environmental issues, such as toxic pollution, have specific targeted effects on species, but are not generally seen as threats at the magnitude of the others.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels fluctuate in a cyclical manner. However, the burning of fossil fuels in recent history has caused a dramatic increase in the levels of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere, which have now reached levels never before seen on Earth. Scientists predict that the addition of this “greenhouse gas” to the atmosphere is resulting in climate change that will significantly impact biodiversity in the coming century.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels fluctuate in a cyclical manner. However, the burning of fossil fuels in recent history has caused a dramatic increase in the levels of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere, which have now reached levels never before seen on Earth. Scientists predict that the addition of this “greenhouse gas” to the atmosphere is resulting in climate change that will significantly impact biodiversity in the coming century.

Habitat Loss

Humans rely on technology to modify their environment and replace certain functions that were once performed by the natural ecosystem. Other species cannot do this. Elimination of their habitat—whether it is a forest, coral reef, grassland, or flowing river—will kill the individuals in the species. Remove the entire habitat within the range of a species and, unless they are one of the few species that do well in human-built environments, the species will become extinct. Human destruction of habitats (habitats generally refer to the part of the ecosystem required by a particular species) accelerated in the latter half of the twentieth century. Consider the exceptional biodiversity of Sumatra: it is home to one species of orangutan, a species of critically endangered elephant, and the Sumatran tiger, but half of Sumatra’s forest is now gone. The neighboring island of Borneo, home to the other species of orangutan, has lost a similar area of forest. Forest loss continues in protected areas of Borneo. The orangutan in Borneo is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), but it is simply the most visible of thousands of species that will not survive the disappearance of the forests of Borneo. The forests are removed for timber and to plant palm oil plantations (Figure below). Palm oil is used in many products including food products, cosmetics, and biodiesel in Europe. A 5-year estimate of global forest cover loss for the years from 2000 to 2005 was 3.1 percent. Much loss (2.4 percent) occurred in the humid tropics where forest loss is primarily from timber extraction. These losses certainly also represent the extinction of species unique to those areas.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): An oil palm plantation in Sabah province Borneo, Malaysia, replaces native forest habitat that a variety of species depended on to live. (credit: Lian Pin Koh)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): An oil palm plantation in Sabah province Borneo, Malaysia, replaces native forest habitat that a variety of species depended on to live. (credit: Lian Pin Koh)

Biology in Action

Preventing Habitat Destruction with Wise Wood ChoicesMost consumers do not imagine that the home improvement products they buy might be contributing to habitat loss and species extinctions. Yet the market for illegally harvested tropical timber is huge, and the wood products often find themselves in building supply stores in the United States. One estimate is that 10 percent of the imported timber stream in the United States, which is the world’s largest consumer of wood products, is potentially illegally logged. In 2006, this amounted to $3.6 billion in wood products. Most of the illegal products are imported from countries that act as intermediaries and are not the originators of the wood.

How is it possible to determine if a wood product, such as flooring, was harvested sustainably or even legally? The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certifies sustainably harvested forest products; therefore, looking for their certification on flooring and other hardwood products is one way to ensure that the wood has not been taken illegally from a tropical forest. Certification applies to specific products, not to a producer; some producers’ products may not have certification while other products are certified. There are certifications other than the FSC, but these are run by timber companies creating a conflict of interest. Another approach is to buy domestic wood species. While it would be great if there was a list of legal versus illegal woods, it is not that simple. Logging and forest management laws vary from country to country; what is illegal in one country may be legal in another. Where and how a product is harvested and whether the forest from which it comes is being sustainably maintained all factor into whether a wood product will be certified by the FSC. It is always a good idea to ask questions about where a wood product came from and how the supplier knows that it was harvested legally.

Habitat destruction can affect ecosystems other than forests. Rivers and streams are important ecosystems and are frequently the target of habitat modification through building and from damming or water removal. Damming of rivers affects flows and access to all parts of a river. Altering a flow regime can reduce or eliminate populations that are adapted to seasonal changes in flow. For example, an estimated 91 percent of river lengths in the United States have been modified with damming or bank modifications. Many fish species in the United States, especially rare species or species with restricted distributions, have seen declines caused by river damming and habitat loss. Research has confirmed that species of amphibians that must carry out parts of their life cycles in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats are at greater risk of population declines and extinction because of the increased likelihood that one of their habitats or access between them will be lost. This is of particular concern because amphibians have been declining in numbers and going extinct more rapidly than many other groups for a variety of possible reasons.

Overharvesting

Overharvesting is a serious threat to many species, but particularly to aquatic species. There are many examples of regulated fisheries (including hunting of marine mammals and harvesting of crustaceans and other species) monitored by fisheries scientists that have nevertheless collapsed. The western Atlantic cod fishery is the most spectacular recent collapse. While it was a hugely productive fishery for 400 years, the introduction of modern factory trawlers in the 1980s and the pressure on the fishery led to it becoming unsustainable. The causes of fishery collapse are both economic and political in nature. Most fisheries are managed as a common resource, available to anyone willing to fish, even when the fishing territory lies within a country’s territorial waters. Common resources are subject to an economic pressure known as the tragedy of the commons, in which fishers have little motivation to exercise restraint in harvesting a fishery when they do not own the fishery. The general outcome of harvests of resources held in common is their overexploitation. While large fisheries are regulated to attempt to avoid this pressure, it still exists in the background. This overexploitation is exacerbated when access to the fishery is open and unregulated and when technology gives fishers the ability to overfish. In a few fisheries, the biological growth of the resource is less than the potential growth of the profits made from fishing if that time and money were invested elsewhere. In these cases—whales are an example—economic forces will drive toward fishing the population to extinction.

Concept in Action

Explore a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service interactive map of critical habitat for endangered and threatened species in the United States. To begin, select “Visit the online mapper.”

For the most part, fishery extinction is not equivalent to biological extinction—the last fish of a species is rarely fished out of the ocean. But there are some instances in which true extinction is a possibility. Whales have slow-growing populations and are at risk of complete extinction through hunting. Also, there are some species of sharks with restricted distributions that are at risk of extinction. The groupers are another population of generally slow-growing fishes that, in the Caribbean, includes a number of species that are at risk of extinction from overfishing.

Coral reefs are extremely diverse marine ecosystems that face peril from several processes. Reefs are home to 1/3 of the world’s marine fish species—about 4000 species—despite making up only one percent of marine habitat. Most home marine aquaria house coral reef species that are wild-caught organisms—not cultured organisms. Although no marine species is known to have been driven extinct by the pet trade, there are studies showing that populations of some species have declined in response to harvesting, indicating that the harvest is not sustainable at those levels. There are also concerns about the effect of the pet trade on some terrestrial species such as turtles, amphibians, birds, plants, and even the orangutans.

Concept in Action

View a brief video discussing the role of marine ecosystems in supporting human welfare and the decline of ocean ecosystems.

Bush meat is the generic term used for wild animals killed for food. Hunting is practiced throughout the world, but hunting practices, particularly in equatorial Africa and parts of Asia, are believed to threaten several species with extinction. Traditionally, bush meat in Africa was hunted to feed families directly; however, recent commercialization of the practice now has bush meat available in grocery stores, which has increased harvest rates to the level of unsustainability. Additionally, human population growth has increased the need for protein foods that are not being met from agriculture. Species threatened by the bush meat trade are mostly mammals including many monkeys and the great apes living in the Congo basin.

Exotic Species

Exotic species are species that have been intentionally or unintentionally introduced by humans into an ecosystem in which they did not evolve. Human transportation of people and goods, including the intentional transport of organisms for trade, has dramatically increased the introduction of species into new ecosystems. These new introductions are sometimes at distances that are well beyond the capacity of the species to ever travel itself and outside the range of the species’ natural predators.

Most exotic species introductions probably fail because of the low number of individuals introduced or poor adaptation to the ecosystem they enter. Some species, however, have characteristics that can make them especially successful in a new ecosystem. These exotic species often undergo dramatic population increases in their new habitat and reset the ecological conditions in the new environment, threatening the species that exist there. When this happens, the exotic species also becomes an invasive species. Invasive species can threaten other species through competition for resources, predation, or disease.

Concept in Action

Explore this interactive global database of exotic or invasive species.

Lakes and islands are particularly vulnerable to extinction threats from introduced species. In Lake Victoria, the intentional introduction of the Nile perch was largely responsible for the extinction of about 200 species of cichlids. The accidental introduction of the brown tree snake via aircraft (Figure below) from the Solomon Islands to Guam in 1950 has led to the extinction of three species of birds and three to five species of reptiles endemic to the island. Several other species are still threatened. The brown tree snake is adept at exploiting human transportation as a means to migrate; one was even found on an aircraft arriving in Corpus Christi, Texas. Constant vigilance on the part of airport, military, and commercial aircraft personnel is required to prevent the snake from moving from Guam to other islands in the Pacific, especially Hawaii. Islands do not make up a large area of land on the globe, but they do contain a disproportionate number of endemic species because of their isolation from mainland ancestors.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): The brown tree snake, Boiga irregularis, is an exotic species that has caused numerous extinctions on the island of Guam since its accidental introduction in 1950. (credit: NPS)

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): The brown tree snake, Boiga irregularis, is an exotic species that has caused numerous extinctions on the island of Guam since its accidental introduction in 1950. (credit: NPS)

Many introductions of aquatic species, both marine and freshwater, have occurred when ships have dumped ballast water taken on at a port of origin into waters at a destination port. Water from the port of origin is pumped into tanks on a ship empty of cargo to increase stability. The water is drawn from the ocean or estuary of the port and typically contains living organisms such as plant parts, microorganisms, eggs, larvae, or aquatic animals. The water is then pumped out before the ship takes on cargo at the destination port, which may be on a different continent. The zebra mussel was introduced to the Great Lakes from Europe prior to 1988 in ship ballast. The zebra mussels in the Great Lakes have cost the industry millions of dollars in clean up costs to maintain water intakes and other facilities. The mussels have also altered the ecology of the lakes dramatically. They threaten native mollusk populations, but have also benefited some species, such as smallmouth bass. The mussels are filter feeders and have dramatically improved water clarity, which in turn has allowed aquatic plants to grow along shorelines, providing shelter for young fish where it did not exist before. The European green crab, Carcinus maenas, was introduced to San Francisco Bay in the late 1990s, likely in ship ballast water, and has spread north along the coast to Washington. The crabs have been found to dramatically reduce the abundance of native clams and crabs with resulting increases in the prey of native crabs.

Invading exotic species can also be disease organisms. It now appears that the global decline in amphibian species recognized in the 1990s is, in some part, caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which causes the disease chytridiomycosis (Figure below). There is evidence that the fungus is native to Africa and may have been spread throughout the world by transport of a commonly used laboratory and pet species: the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. It may well be that biologists themselves are responsible for spreading this disease worldwide. The North American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, which has also been widely introduced as a food animal but which easily escapes captivity, survives most infections of B. dendrobatidis and can act as a reservoir for the disease.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): This Limosa harlequin frog (Atelopus limosus), an endangered species from Panama, died from a fungal disease called chytridiomycosis. The red lesions are symptomatic of the disease. (credit: Brian Gratwicke)

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): This Limosa harlequin frog (Atelopus limosus), an endangered species from Panama, died from a fungal disease called chytridiomycosis. The red lesions are symptomatic of the disease. (credit: Brian Gratwicke)

Early evidence suggests that another fungal pathogen, Geomyces destructans, introduced from Europe is responsible for white-nose syndrome, which infects cave-hibernating bats in eastern North America and has spread from a point of origin in western New York State (Figure below). The disease has decimated bat populations and threatens extinction of species already listed as endangered: the Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis, and potentially the Virginia big-eared bat, Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus. How the fungus was introduced is unknown, but one logical presumption would be that recreational cavers unintentionally brought the fungus on clothes or equipment from Europe.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): This little brown bat in Greeley Mine, Vermont, March 26, 2009, was found to have white-nose syndrome. (credit: modification of work by Marvin Moriarty, USFWS)

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): This little brown bat in Greeley Mine, Vermont, March 26, 2009, was found to have white-nose syndrome. (credit: modification of work by Marvin Moriarty, USFWS)

Climate Change

Climate change, and specifically the anthropogenic warming trend presently underway, is recognized as a major extinction threat, particularly when combined with other threats such as habitat loss. Anthropogenic warming of the planet has been observed and is hypothesized to continue due to past and continuing emission of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide and methane, into the atmosphere caused by the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation. These gases decrease the degree to which Earth is able to radiate heat energy created by the sunlight that enters the atmosphere. The changes in climate and energy balance caused by increasing greenhouse gases are complex and our understanding of them depends on predictions generated from detailed computer models. Scientists generally agree the present warming trend is caused by humans and some of the likely effects include dramatic and dangerous climate changes in the coming decades. However, there is still debate and a lack of understanding about specific outcomes. Scientists disagree about the likely magnitude of the effects on extinction rates, with estimates ranging from 15 to 40 percent of species committed to extinction by 2050. Scientists do agree that climate change will alter regional climates, including rainfall and snowfall patterns, making habitats less hospitable to the species living in them. The warming trend will shift colder climates toward the north and south poles, forcing species to move with their adapted climate norms, but also to face habitat gaps along the way. The shifting ranges will impose new competitive regimes on species as they find themselves in contact with other species not present in their historic range. One such unexpected species contact is between polar bears and grizzly bears. Previously, these two species had separate ranges. Now, their ranges are overlapping and there are documented cases of these two species mating and producing viable offspring. Changing climates also throw off the delicate timing adaptations that species have to seasonal food resources and breeding times. Scientists have already documented many contemporary mismatches to shifts in resource availability and timing.

Range shifts are already being observed: for example, on average, European bird species ranges have moved 91 km (56.5 mi) northward. The same study suggested that the optimal shift based on warming trends was double that distance, suggesting that the populations are not moving quickly enough. Range shifts have also been observed in plants, butterflies, other insects, freshwater fishes, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals.

Climate gradients will also move up mountains, eventually crowding species higher in altitude and eliminating the habitat for those species adapted to the highest elevations. Some climates will completely disappear. The rate of warming appears to be accelerated in the arctic, which is recognized as a serious threat to polar bear populations that require sea ice to hunt seals during the winter months: seals are the only source of protein available to polar bears. A trend to decreasing sea ice coverage has occurred since observations began in the mid-twentieth century. The rate of decline observed in recent years is far greater than previously predicted by climate models (Figure below).

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The effect of global warming can be seen in the continuing retreat of Grinnell Glacier. The mean annual temperature in Glacier National Park has increased 1.33°C since 1900. The loss of a glacier results in the loss of summer meltwaters, sharply reducing seasonal water supplies and severely affecting local ecosystems. (credit: USGS, GNP Archives)

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The effect of global warming can be seen in the continuing retreat of Grinnell Glacier. The mean annual temperature in Glacier National Park has increased 1.33°C since 1900. The loss of a glacier results in the loss of summer meltwaters, sharply reducing seasonal water supplies and severely affecting local ecosystems. (credit: USGS, GNP Archives)

Finally, global warming will raise ocean levels due to meltwater from glaciers and the greater volume occupied by warmer water. Shorelines will be inundated, reducing island size, which will have an effect on some species, and a number of islands will disappear entirely. Additionally, the gradual melting and subsequent refreezing of the poles, glaciers, and higher elevation mountains—a cycle that has provided freshwater to environments for centuries—will be altered. This could result in an overabundance of salt water and a shortage of fresh water.