8.1.1: Importance of Biodiversity

- Page ID

- 11777

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): This tropical lowland rainforest in Madagascar is an example of a high biodiversity habitat. This particular location is protected within a national forest, yet only 10 percent of the original coastal lowland forest remains, and research suggests half the original biodiversity has been lost. (credit: Frank Vassen)

Biodiversity is a broad term for biological variety, and it can be measured at a number of organizational levels. Traditionally, ecologists have measured biodiversity by taking into account both the number of species and the number of individuals in each of those species. However, biologists are using measures of biodiversity at several levels of biological organization (including genes, populations, and ecosystems) to help focus efforts to preserve the biologically and technologically important elements of biodiversity.

When biodiversity loss through extinction is thought of as the loss of the passenger pigeon, the dodo, or, even, the woolly mammoth there seems to be no reason to care about it because these events happened long ago. How is the loss practically important for the welfare of the human species? Would these species have made our lives any better? From the perspective of evolution and ecology, the loss of a particular individual species, with some exceptions, may seem unimportant, but the current accelerated extinction rate means the loss of tens of thousands of species within our lifetimes. Much of this loss is occurring in tropical rainforests like the one pictured in image above, which are especially high-diversity ecosystems that are being cleared for timber and agriculture. This is likely to have dramatic effects on human welfare through the collapse of ecosystems and in added costs to maintain food production, clean air and water, and improve human health.

Biologists recognize that human populations are embedded in ecosystems and are dependent on them, just as is every other species on the planet. Agriculture began after early hunter-gatherer societies first settled in one place and heavily modified their immediate environment: the ecosystem in which they existed. This cultural transition has made it difficult for humans to recognize their dependence on living things other than crops and domesticated animals on the planet. Today our technology smoothes out the extremes of existence and allows many of us to live longer, more comfortable lives, but ultimately the human species cannot exist without its surrounding ecosystems. Our ecosystems provide our food. This includes living plants that grow in soil ecosystems and the animals that eat these plants (or other animals) as well as photosynthetic organisms in the oceans and the other organisms that eat them. Our ecosystems have provided and will provide many of the medications that maintain our health, which are commonly made from compounds found in living organisms. Ecosystems provide our clean water, which is held in lake and river ecosystems or passes through terrestrial ecosystems on its way into groundwater.

Types of Biodiversity

A common meaning of biodiversity is simply the number of species in a location or on Earth; for example, the American Ornithologists’ Union lists 2078 species of birds in North and Central America. This is one measure of the bird biodiversity on the continent. More sophisticated measures of diversity take into account the relative abundances of species. For example, a forest with 10 equally common species of trees is more diverse than a forest that has 10 species of trees wherein just one of those species makes up 95 percent of the trees rather than them being equally distributed. Biologists have also identified alternate measures of biodiversity, some of which are important in planning how to preserve biodiversity.

Genetic and Chemical Biodiversity

Genetic diversity is one alternate concept of biodiversity. Genetic diversity (or variation) is the raw material for adaptation in a species. A species’ future potential for adaptation depends on the genetic diversity held in the genomes of the individuals in populations that make up the species. The same is true for higher taxonomic categories. A genus with very different types of species will have more genetic diversity than a genus with species that look alike and have similar ecologies. The genus with the greatest potential for subsequent evolution is the most genetically diverse one.

Most genes code for proteins, which in turn carry out the metabolic processes that keep organisms alive and reproducing. Genetic diversity can also be conceived of as chemical diversity in that species with different genetic makeups produce different assortments of chemicals in their cells (proteins as well as the products and byproducts of metabolism). This chemical diversity is important for humans because of the potential uses for these chemicals, such as medications. For example, the drug eptifibatide is derived from rattlesnake venom and is used to prevent heart attacks in individuals with certain heart conditions.

At present, it is far cheaper to discover compounds made by an organism than to imagine them and then synthesize them in a laboratory. Chemical diversity is one way to measure diversity that is important to human health and welfare. Through selective breeding, humans have domesticated animals, plants, and fungi, but even this diversity is suffering losses because of market forces and increasing globalism in human agriculture and migration. For example, international seed companies produce only a very few varieties of a given crop and provide incentives around the world for farmers to buy these few varieties while abandoning their traditional varieties, which are far more diverse. The human population depends on crop diversity directly as a stable food source and its decline is troubling to biologists and agricultural scientists.

Ecosystems Diversity

It is also useful to define ecosystem diversity: the number of different ecosystems on Earth or in a geographical area. Whole ecosystems can disappear even if some of the species might survive by adapting to other ecosystems. The loss of an ecosystem means the loss of the interactions between species, the loss of unique features of coadaptation, and the loss of biological productivity that an ecosystem is able to create. An example of a largely extinct ecosystem in North America is the prairie ecosystem (Figure below). Prairies once spanned central North America from the boreal forest in northern Canada down into Mexico. They are now all but gone, replaced by crop fields, pasture lands, and suburban sprawl. Many of the species survive, but the hugely productive ecosystem that was responsible for creating our most productive agricultural soils is now gone. As a consequence, their soils are now being depleted unless they are maintained artificially at greater expense. The decline in soil productivity occurs because the interactions in the original ecosystem have been lost; this was a far more important loss than the relatively few species that were driven extinct when the prairie ecosystem was destroyed.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): The variety of ecosystems on Earth—from coral reef to prairie—enables a great diversity of species to exist. (credit “coral reef”: modification of work by Jim Maragos, USFWS; credit: “prairie”: modification of work by Jim Minnerath, USFWS)

Current Species Diversity

Despite considerable effort, knowledge of the species that inhabit the planet is limited. A recent estimate suggests that the eukaryote species for which science has names, about 1.5 million species, account for less than 20 percent of the total number of eukaryote species present on the planet (8.7 million species, by one estimate). Estimates of numbers of prokaryotic species are largely guesses, but biologists agree that science has only just begun to catalog their diversity. Even with what is known, there is no centralized repository of names or samples of the described species; therefore, there is no way to be sure that the 1.5 million descriptions is an accurate number. It is a best guess based on the opinions of experts on different taxonomic groups. Given that Earth is losing species at an accelerating pace, science knows little about what is being lost. Table below presents recent estimates of biodiversity in different groups.

| Source: Mora et al 2011 | Source: Chapman | Source: Groombridge and Jenkins 2002 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Described | Predicted | Described | Predicted | Described | Predicted | |

| Animals | 1,124,516 | 9,920,000 | 1,424,153 | 6,836,330 | 1,225,500 | 10,820,000 |

| Photosynthetic protists | 17,892 | 34,900 | 25,044 | 200,500 | - | - |

| Fungi | 44,368 | 616,320 | 98,998 | 1,500,000 | 72,000 | 1,500,000 |

| Plants | 224,244 | 314,600 | 310,129 | 390,800 | 270,000 | 320,000 |

| Non-photosynthetic protists | 16,236 | 72,800 | 28,871 | 1,000,000 | 80,000 | 600,000 |

| Prokaryotes | - | - | 10,307 | 1,000,000 | 10,175 | - |

| Total | 1,438,769 | 10,960,000 | 1,897,502 | 10,897,630 | 1,657,675 | 13,240,000 |

This table shows the estimated number of species by taxonomic group—including both described (named and studied) and predicted (yet to be named) species.

There are various initiatives to catalog described species in accessible and more organized ways, and the internet is facilitating that effort. Nevertheless, at the current rate of species description, which according to the State of Observed Species1 reports is 17,000–20,000 new species a year, it would take close to 500 years to describe all of the species currently in existence. The task, however, is becoming increasingly impossible over time as extinction removes species from Earth faster than they can be described.

Naming and counting species may seem an unimportant pursuit given the other needs of humanity, but it is not simply an accounting. Describing species is a complex process by which biologists determine an organism’s unique characteristics and whether or not that organism belongs to any other described species. It allows biologists to find and recognize the species after the initial discovery to follow up on questions about its biology. That subsequent research will produce the discoveries that make the species valuable to humans and to our ecosystems. Without a name and description, a species cannot be studied in depth and in a coordinated way by multiple scientists.

Patterns of Biodiversity

Biodiversity is not evenly distributed on the planet. Lake Victoria contained almost 500 species of cichlids (only one family of fishes present in the lake) before the introduction of an exotic species in the 1980s and 1990s caused a mass extinction. All of these species were found only in Lake Victoria, which is to say they were endemic. Endemic species are found in only one location. For example, the blue jay is endemic to North America, while the Barton Springs salamander is endemic to the mouth of one spring in Austin, Texas. Endemics with highly restricted distributions, like the Barton Springs salamander, are particularly vulnerable to extinction. Higher taxonomic levels, such as genera and families, can also be endemic.

Lake Huron contains about 79 species of fish, all of which are found in many other lakes in North America. What accounts for the difference in diversity between Lake Victoria and Lake Huron? Lake Victoria is a tropical lake, while Lake Huron is a temperate lake. Lake Huron in its present form is only about 7,000 years old, while Lake Victoria in its present form is about 15,000 years old. These two factors, latitude and age, are two of several hypotheses biogeographers have suggested to explain biodiversity patterns on Earth.

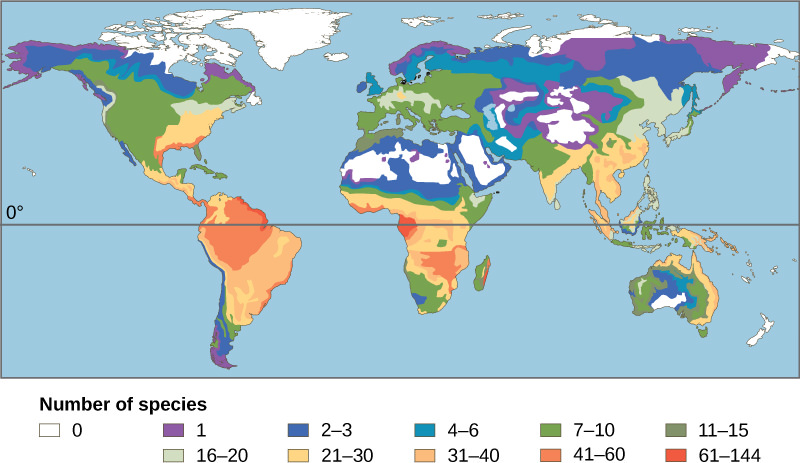

One of the oldest observed patterns in ecology is that biodiversity in almost every taxonomic group of organism increases as latitude declines. In other words, biodiversity increases closer to the equator (Figure below).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): This map illustrates the number of amphibian species across the globe and shows the trend toward higher biodiversity at lower latitudes. A similar pattern is observed for most taxonomic groups.

It is not yet clear why biodiversity increases closer to the equator, but hypotheses include the greater age of the ecosystems in the tropics versus temperate regions, which were largely devoid of life or drastically impoverished during the last ice age. The greater age provides more time for speciation. Another possible explanation is the greater energy the tropics receive from the sun versus the lesser energy input in temperate and polar regions. But scientists have not been able to explain how greater energy input could translate into more species. The complexity of tropical ecosystems may promote speciation by increasing the habitat heterogeneity, or number of ecological niches, in the tropics relative to higher latitudes. The greater heterogeneity provides more opportunities for coevolution, specialization, and perhaps greater selection pressures leading to population differentiation. However, this hypothesis suffers from some circularity—ecosystems with more species encourage speciation, but how did they get more species to begin with? The tropics have been perceived as being more stable than temperate regions, which have a pronounced climate and day-length seasonality. The tropics have their own forms of seasonality, such as rainfall, but they are generally assumed to be more stable environments and this stability might promote speciation.

Regardless of the mechanisms, it is certainly true that biodiversity is greatest in the tropics. The number of endemic species is higher in the tropics. The tropics also contain more biodiversity hotspots. At the same time, our knowledge of the species living in the tropics is lowest and because of recent, heavy human activity the potential for biodiversity loss is greatest.

Importance of Biodiversity

Loss of biodiversity eventually threatens other species we do not impact directly because of their interconnectedness; as species disappear from an ecosystem other species are threatened by the changes in available resources. Biodiversity is important to the survival and welfare of human populations because it has impacts on our health and our ability to feed ourselves through agriculture and harvesting populations of wild animals.

Human Health

Many medications are derived from natural chemicals made by a diverse group of organisms. For example, many plants produce secondary plant compounds, which are toxins used to protect the plant from insects and other animals that eat them. Some of these secondary plant compounds also work as human medicines. Contemporary societies that live close to the land often have a broad knowledge of the medicinal uses of plants growing in their area. For centuries in Europe, older knowledge about the medical uses of plants was compiled in herbals—books that identified the plants and their uses. Humans are not the only animals to use plants for medicinal reasons. The other great apes, orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas have all been observed self-medicating with plants.

Modern pharmaceutical science also recognizes the importance of these plant compounds. Examples of significant medicines derived from plant compounds include aspirin, codeine, digoxin, atropine, and vincristine (Figure below). Many medications were once derived from plant extracts but are now synthesized. It is estimated that, at one time, 25 percent of modern drugs contained at least one plant extract. That number has probably decreased to about 10 percent as natural plant ingredients are replaced by synthetic versions of the plant compounds. Antibiotics, which are responsible for extraordinary improvements in health and lifespans in developed countries, are compounds largely derived from fungi and bacteria.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Catharanthus roseus, the Madagascar periwinkle, has various medicinal properties. Among other uses, it is a source of vincristine, a drug used in the treatment of lymphomas. (credit: Forest and Kim Starr)

In recent years, animal venoms and poisons have excited intense research for their medicinal potential. By 2007, the FDA had approved five drugs based on animal toxins to treat diseases such as hypertension, chronic pain, and diabetes. Another five drugs are undergoing clinical trials and at least six drugs are being used in other countries. Other toxins under investigation come from mammals, snakes, lizards, various amphibians, fish, snails, octopuses, and scorpions.

Aside from representing billions of dollars in profits, these medications improve people’s lives. Pharmaceutical companies are actively looking for new natural compounds that can function as medicines. It is estimated that one third of pharmaceutical research and development is spent on natural compounds and that about 35 percent of new drugs brought to market between 1981 and 2002 were from natural compounds.

Finally, it has been argued that humans benefit psychologically from living in a biodiverse world. The chief proponent of this idea is entomologist E. O. Wilson. He argues that human evolutionary history has adapted us to living in a natural environment and that built environments generate stresses that affect human health and well-being. There is considerable research into the psychologically regenerative benefits of natural landscapes that suggest the hypothesis may hold some truth.

Agricultural

Since the beginning of human agriculture more than 10,000 years ago, human groups have been breeding and selecting crop varieties. This crop diversity matched the cultural diversity of highly subdivided populations of humans. For example, potatoes were domesticated beginning around 7,000 years ago in the central Andes of Peru and Bolivia. The people in this region traditionally lived in relatively isolated settlements separated by mountains. The potatoes grown in that region belong to seven species and the number of varieties likely is in the thousands. Each variety has been bred to thrive at particular elevations and soil and climate conditions. The diversity is driven by the diverse demands of the dramatic elevation changes, the limited movement of people, and the demands created by crop rotation for different varieties that will do well in different fields.

Potatoes are only one example of agricultural diversity. Every plant, animal, and fungus that has been cultivated by humans has been bred from original wild ancestor species into diverse varieties arising from the demands for food value, adaptation to growing conditions, and resistance to pests. The potato demonstrates a well-known example of the risks of low crop diversity: during the tragic Irish potato famine (1845–1852 AD), the single potato variety grown in Ireland became susceptible to a potato blight—wiping out the crop. The loss of the crop led to famine, death, and mass emigration. Resistance to disease is a chief benefit to maintaining crop biodiversity and lack of diversity in contemporary crop species carries similar risks. Seed companies, which are the source of most crop varieties in developed countries, must continually breed new varieties to keep up with evolving pest organisms. These same seed companies, however, have participated in the decline of the number of varieties available as they focus on selling fewer varieties in more areas of the world replacing traditional local varieties.

The ability to create new crop varieties relies on the diversity of varieties available and the availability of wild forms related to the crop plant. These wild forms are often the source of new gene variants that can be bred with existing varieties to create varieties with new attributes. Loss of wild species related to a crop will mean the loss of potential in crop improvement. Maintaining the genetic diversity of wild species related to domesticated species ensures our continued supply of food.

Since the 1920s, government agriculture departments have maintained seed banks of crop varieties as a way to maintain crop diversity. This system has flaws because over time seed varieties are lost through accidents and there is no way to replace them. In 2008, the Svalbard Global seed Vault, located on Spitsbergen island, Norway, (Figure below) began storing seeds from around the world as a backup system to the regional seed banks. If a regional seed bank stores varieties in Svalbard, losses can be replaced from Svalbard should something happen to the regional seeds. The Svalbard seed vault is deep into the rock of the arctic island. Conditions within the vault are maintained at ideal temperature and humidity for seed survival, but the deep underground location of the vault in the arctic means that failure of the vault’s systems will not compromise the climatic conditions inside the vault.

Art Connection

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a storage facility for seeds of Earth’s diverse crops. (credit: Mari Tefre, Svalbard Global Seed Vault)

The Svalbard seed vault is located on Spitsbergen island in Norway, which has an arctic climate. Why might an arctic climate be good for seed storage?

Although crops are largely under our control, our ability to grow them is dependent on the biodiversity of the ecosystems in which they are grown. That biodiversity creates the conditions under which crops are able to grow through what are known as ecosystem services—valuable conditions or processes that are carried out by an ecosystem. Crops are not grown, for the most part, in built environments. They are grown in soil. Although some agricultural soils are rendered sterile using controversial pesticide treatments, most contain a huge diversity of organisms that maintain nutrient cycles—breaking down organic matter into nutrient compounds that crops need for growth. These organisms also maintain soil texture that affects water and oxygen dynamics in the soil that are necessary for plant growth. Replacing the work of these organisms in forming arable soil is not practically possible. These kinds of processes are called ecosystem services. They occur within ecosystems, such as soil ecosystems, as a result of the diverse metabolic activities of the organisms living there, but they provide benefits to human food production, drinking water availability, and breathable air.

Other key ecosystem services related to food production are plant pollination and crop pest control. It is estimated that honeybee pollination within the United States brings in $1.6 billion per year; other pollinators contribute up to $6.7 billion. Over 150 crops in the United States require pollination to produce. Many honeybee populations are managed by beekeepers who rent out their hives’ services to farmers. Honeybee populations in North America have been suffering large losses caused by a syndrome known as colony collapse disorder, a new phenomenon with an unclear cause. Other pollinators include a diverse array of other bee species and various insects and birds. Loss of these species would make growing crops requiring pollination impossible, increasing dependence on other crops.

Finally, humans compete for their food with crop pests, most of which are insects. Pesticides control these competitors, but these are costly and lose their effectiveness over time as pest populations adapt. They also lead to collateral damage by killing non-pest species as well as beneficial insects like honeybees, and risking the health of agricultural workers and consumers. Moreover, these pesticides may migrate from the fields where they are applied and do damage to other ecosystems like streams, lakes, and even the ocean. Ecologists believe that the bulk of the work in removing pests is actually done by predators and parasites of those pests, but the impact has not been well studied. A review found that in 74 percent of studies that looked for an effect of landscape complexity (forests and fallow fields near to crop fields) on natural enemies of pests, the greater the complexity, the greater the effect of pest-suppressing organisms. Another experimental study found that introducing multiple enemies of pea aphids (an important alfalfa pest) increased the yield of alfalfa significantly. This study shows that a diversity of pests is more effective at control than one single pest. Loss of diversity in pest enemies will inevitably make it more difficult and costly to grow food. The world’s growing human population faces significant challenges in the increasing costs and other difficulties associated with producing food.

Wild Food Sources

In addition to growing crops and raising food animals, humans obtain food resources from wild populations, primarily wild fish populations. For about one billion people, aquatic resources provide the main source of animal protein. But since 1990, production from global fisheries has declined. Despite considerable effort, few fisheries on Earth are managed sustainability.

Fishery extinctions rarely lead to complete extinction of the harvested species, but rather to a radical restructuring of the marine ecosystem in which a dominant species is so over-harvested that it becomes a minor player, ecologically. In addition to humans losing the food source, these alterations affect many other species in ways that are difficult or impossible to predict. The collapse of fisheries has dramatic and long-lasting effects on local human populations that work in the fishery. In addition, the loss of an inexpensive protein source to populations that cannot afford to replace it will increase the cost of living and limit societies in other ways. In general, the fish taken from fisheries have shifted to smaller species and the larger species are overfished. The ultimate outcome could clearly be the loss of aquatic systems as food sources.