7.1: Food Security

- Page ID

- 11772

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Progress continues in the fight against hunger, yet an unacceptably large number of people still lack the food they need for an active and healthy life. The latest available estimates indicate that about 795 million people in the world – just over one in nine –still go to bed hungry every night, and an even greater number live in poverty (defined as living on less than $1.25 per day). Poverty—not food availability—is the major driver of food insecurity. Improvements in agricultural productivity are necessary to increase rural household incomes and access to available food but are insufficient to ensure food security. Evidence indicates that poverty reduction and food security do not necessarily move in tandem. The main problem is lack of economic (social and physical) access to food at national and household levels and inadequate nutrition (or hidden hunger). Food security not only requires an adequate supply of food but also entails availability, access, and utilization by all—men and women of all ages, ethnicities, religions, and socioeconomic levels.

From Agriculture to Food Security

Agriculture and food security are inextricably linked. The agricultural sector in each country is dependent on the available natural resources, as well as on national and international policy and the institutional environment that governs those resources. These factors influence women and men in their choice of crops and levels of potential productivity. Agriculture, whether domestic or international, is the only source of food both for direct consumption and as raw material for refined foods. Agricultural production determines food availability. The stability of access to food through production or purchase is governed by domestic policies, including social protection policies and agricultural investment choices that reduce risks (such as droughts) in the agriculture production cycle. Yet the production of food is not the only goal of agricultural systems that also produce feed for livestock and fuel. Therefore, demand for and policies related to feed and fuel also influence food availability and access.

Staple grains are the main source of dietary energy in the human diet and are more likely to be available through national and international markets, even in developing countries, given their storage and transport characteristics. Fruits, vegetables, livestock, and aquaculture products are the key to micronutrient, that is, vitamins and minerals, sufficiency. However, most of these products are more perishable than grains, so that in the poorest countries where lack of infrastructure, such as cold storage and refrigerated transport, predicates short food chains, local agriculture determines the diversity of diets. Food security can become a reality only when the agricultural sector is vibrant.

Women’s Role in Food and Nutritional Security

Agricultural interventions are most likely to affect nutrition outcomes when they involve diverse and complementary processes and strategies that redirect the focus beyond agriculture for food production and toward broader consideration of livelihoods, women’s empowerment, and optimal intrahousehold uses of resources. Successful projects are those that invest broadly in improving human capital, sustain and increase the livelihood assets of the poor, and focus on gender equality. Women are crucial in the translation of the products of a vibrant agriculture sector into food and nutritional security for their households. They are often the farmers who cultivate food crops and produce commercial crops alongside the men in their households as a source of income. When women have an income, substantial evidence indicates that the income is more likely to be spent on food and children’s needs. Women are generally responsible for food selection and preparation and for the care and feeding of children. Women are the key to food security for their households (Quisumbing and others 1995). In rural areas the availability and use of time by women is also a key factor in the availability of water for good hygiene, firewood collection, and frequent feeding of small children. In sub-Saharan Africa transportation of supplies for domestic use—fetching fuelwood and water—is largely done by women and girls on foot.

Changes in the availability of natural resources, due to the depletion of natural resources and/or impacts of climate change, can compromise food security by further constraining the time available to women. Water degradation and pollution can force women to travel farther to collect water, reduce the amount they collect, and compromise hygiene practices in the household. Recognizing women’s needs for environmental resources, not only for crop production but also for fuel and water, and building these into good environmental management can release more time for women to use on income generation, child care, and leisure.

Food security

Food security is essentially built on four pillars: availability, access, utilization and stability. An individual must have access to sufficient food of the right dietary mix (quality) at all times to be food secure. Those who never have sufficient quality food are chronically food insecure.

What is Food Security?

Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (FAO 2006).

It includes the following dimensions: availability: the availability of sufficient quantities of appropriate quality; access: access by individuals to adequate resources for acquiring appropriate foods for a nutritious diet on a regular basis; utilization: utilization of food through adequate diet, clean water, sanitation and health care to reach a nutritional well-being where all physiological needs are met; stability: a population, household or individual must have access to food at all times and should not risk losing access as a consequence of sudden shocks or cyclical events.

Certain groups are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity, including women (especially low income pregnant and lactating women), victims of conflict, the ill, migrant workers, low-income urban dwellers, the elderly, and children under five.

The definition of food security is often applied at varying levels of aggregation, despite its articulation at the individual level. The importance of a pillar depends on the level of aggregation being addressed. At a global level, the important pillar is food availability. Does global agricultural activity produce sufficient food to feed all the world’s inhabitants? The answer today is yes, but it may not be true in the future given the impact of a growing world population, emerging plant and animal pests and diseases, declining soil productivity and environmental quality, increasing use of land for fuel rather than food, and lack of attention to agricultural research and development, among other factors.

When food security is analyzed at the national level, an understanding not only of national production is important, but also of the country’s access to food from the global market, its foreign exchange earnings, and its citizens’ consumer choices. Food security analyzed at the household level is conditioned by a household’s own food production and household members’ ability to purchase food of the right quality and diversity in the market place. However, it is only at the individual level that the analysis can be truly accurate because only through understanding who consumes what can we appreciate the impact of sociocultural and gender inequalities on people’s ability to meet their nutritional needs.

The third pillar, food utilization, essentially translates the food available to a household into nutritional security for its members. One aspect of utilization is analyzed in terms of distribution according to need. Nutritional standards exist for the actual nutritional needs of men, women, boys, and girls of different ages and life phases (that is, pregnant women), but these “needs” are often socially constructed based on culture. For example, in South Asia evidence shows that women eat after everyone else has eaten at a meal and are less likely than men in the same household to consume preferred foods such as meats and fish. Hidden hunger commonly results from poor food utilization: that is, a person’s diet lacks the appropriate balance of macro- (calories) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals). Individuals may look well nourished and consume sufficient calories but be deficient in key micronutrients such as vitamin A, iron, and iodine.

When food security is analyzed at the national level, an understanding not only of national production is important, but also of the country’s access to food from the global market, its foreign exchange earnings, and its citizens’ consumer choices. Food security analyzed at the household level is conditioned by a household’s own food production and household members’ ability to purchase food of the right quality and diversity in the market place. However, it is only at the individual level that the analysis can be truly accurate because only through understanding who consumes what can we appreciate the impact of sociocultural and gender inequalities on people’s ability to meet their nutritional needs.

Malnutrition is economically costly: it can cost individuals 10 percent of their lifetime earnings and nations 2 to 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the worst-affected countries (Alderman 2005). Achieving food security is even more challenging in the context of HIV and AIDS. HIV affects people’s physical ability to produce and use food, reallocating household labor, increasing the work burden on women, and preventing widows and children from inheriting land and productive resources (Izumi 2006).

Public policies, written from a human rights perspective, recognize the interrelatedness of all basic rights and assist in the identification of those whose rights are not fully realized. In this way they facilitate corrective action and appropriate strategies to enable equal protection for all. Equal representation and active engagement of both women and men in the policymaking processes are required so that their varying needs and priorities are appropriately targeted. More often than not, however, access to the legal system may be more problematic for women than men, but technical and financial support is also needed if institutions that advance and implement women’s rights are to fulfill their mandate.

Recognizing the Role of Women Can Improve Food and and Nutritional Security

Food security is a primary goal of sustainable agricultural development and a cornerstone for economic and social development. Women play vital and often unacknowledged role in agriculture. Gender-based inequalities all along the food production chain “from farm to plate” impede the attainment of food and nutritional security. Maximizing the impact of agricultural development on food security entails enhancing women’s roles as agricultural producers as well as the primary caretakers of their families.

Obesity

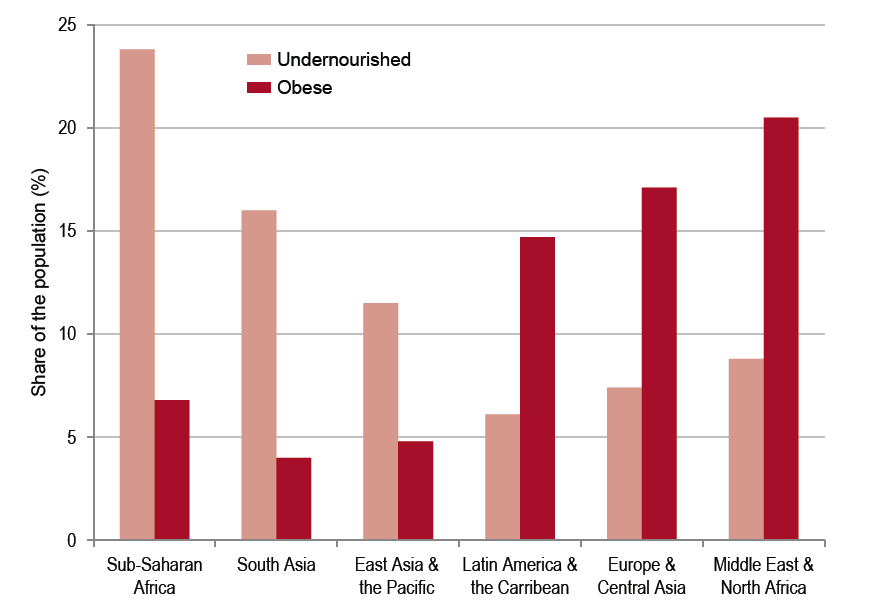

Obesity means having too much body fat. It is not the same as overweight, which means weighing too much. Obesity has become a significant global health challenge, yet is preventable and reversible. Over the past 20 years, a global overweight/obesity epidemic has emerged, initially in industrial countries and now increasingly in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in urban settings, resulting in a triple burden of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency, and overweight/obesity. There is significant variation by region; some have very high rates of undernourishment and low rates of obesity, while in other regions the opposite is true (Figure below).

However, obesity has increased to the extent that the number of overweight people now exceeds the number of underweight people worldwide. The economic cost of obesity has been estimated at $2 trillion, accounting for about 5 percent of deaths worldwide. Almost 30 percent of the world’s population, or 2.1 billion people, are overweight or obese, 62 percent of whom live in developing countries.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Obesity and undernourishment by region.

Obesity accounts for a growing level and share of worldwide noncommunicable diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers that can reduce quality of life and increase public health costs of already under-resourced developing countries. The number of overweight children is projected to double by 2030. Driven primarily by increasing availability of processed, affordable, and effectively marketed food, the global food system is falling short with rising obesity and related poor health outcomes. Due to established health implications and rapid increase in prevalence, obesity is now a recognized major global health challenge, and no national success stories in curbing its growth have so far been reported.