16.4: Ocean-Wave Spectra

- Page ID

- 30170

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Ocean waves are produced by the wind. The faster the wind, the longer the wind blows, and the bigger the area over which the wind blows, the bigger the waves. In designing ships or offshore structures we wish to know the biggest waves produced by a given wind speed. Suppose the wind blows at 20 m/s for many days over a large area of the North Atlantic. What will be the spectrum of ocean waves at the downwind side of the area?

Pierson-Moskowitz Spectrum

Various idealized spectra are used to answer the question in oceanography and ocean engineering. Perhaps the simplest is that proposed by Pierson and Moskowitz (1964). They assumed that if the wind blew steadily for a long time over a large area, the waves would come into equilibrium with the wind. This is the concept of a fully developed sea. Here, a “long time” is roughly ten-thousand wave periods, and a “large area” is roughly five-thousand wave lengths on a side.

To obtain a spectrum of a fully developed sea, they used measurements of waves made by accelerometers on British weather ships in the north Atlantic. First, they selected wave data for times when the wind had blown steadily for long times over large areas of the north Atlantic. Then they calculated the wave spectra for various wind speeds (figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), and they found that the function \[S(\omega) = \frac{\alpha g^{2}}{\omega^{5}} \exp \left[-\beta \left(\frac{\omega_{0}}{\omega}\right)^{4}\right] \nonumber \]

was a good fit to the observed spectra, where \(\omega = 2\pi f\), \(f\) is the wave frequency in Hertz, \(\alpha = 8.1 \times 10^{-3}\), \(\beta = 0.74\), \(\omega_{0} = g/U_{19.5}\) and \(U_{19.5}\) is the wind speed at a height of 19.5 m above the sea surface, the height of the anemometers on the weather ships used by Pierson and Moskowitz (1964).

For most airflow over the sea the atmospheric boundary layer has nearly neutral stability, and \[U_{19.5} \approx 1.026 U_{10} \nonumber \]assuming a drag coefficient of \(1.3 \times 10^{-3}\).

The frequency of the peak of the Pierson-Moskowitz spectrum is calculated by solving \(dS/d \omega = 0\) for \(\omega_{p}\), to obtain \[\omega_{p} = 0.877 g/U_{19.5} \nonumber \]

The speed of waves at the peak is calculated from \((16.1.7)\), which gives: \[c_{p} = \frac{g}{\omega_{p}} = 1.14 U_{19.5} \approx 1.17 U_{10} \nonumber \]

Hence waves with frequency \(\omega_{p}\) travel 14% faster than the wind at a height of 19.5 m or 17% faster than the wind at a height of 10 m. This poses a difficult problem: How can the wind produce waves traveling faster than the wind? I will return to the problem after I discuss the JONSWAP spectrum and the influence of nonlinear interactions among wind-generated waves.

By integrating \(S(\omega)\) over all \(\omega\) we get the variance of surface elevation: \[\langle \zeta^{2} \rangle = \int_{0}^{\infty} S(\omega) \ d \omega = 2.74 \times 10^{-3} \frac{\left(U_{19.5}\right)^{4}}{g^{2}} \nonumber \]

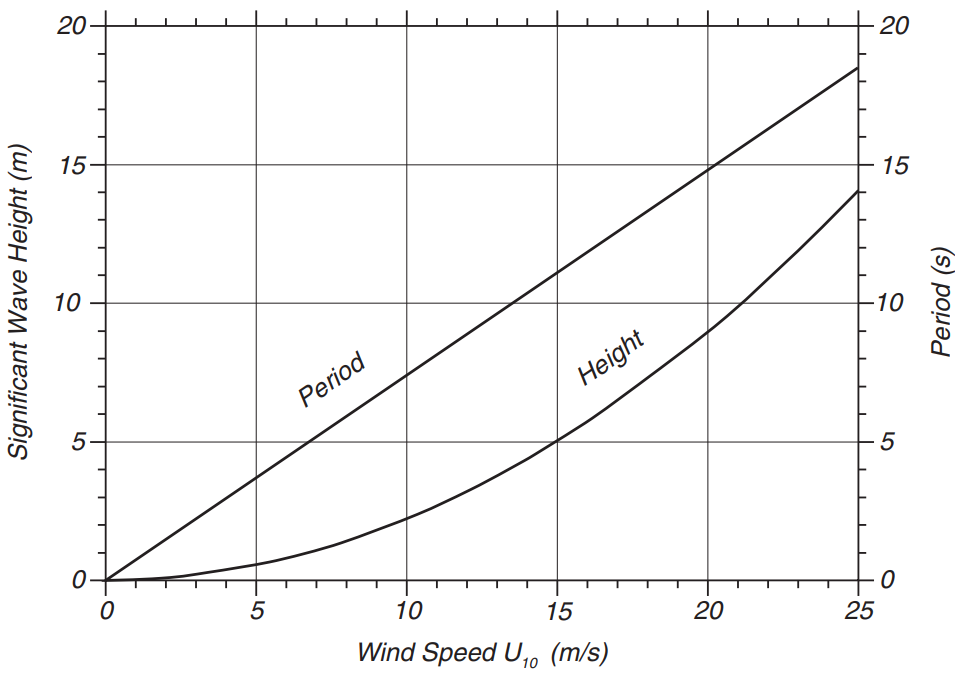

Remembering that \(H_{1/3} = 4 \langle \zeta^{2} \rangle^{1/2}\), the significant wave height is: \[H_{1/3} = 0.21 \frac{\left(U_{19.5}\right)^{2}}{g} \approx 0.22 \frac{\left(U_{10}\right)^{2}}{g} \nonumber \]

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) gives significant wave heights and periods for the Pierson-Moskowitz spectrum.

JONSWAP Spectrum

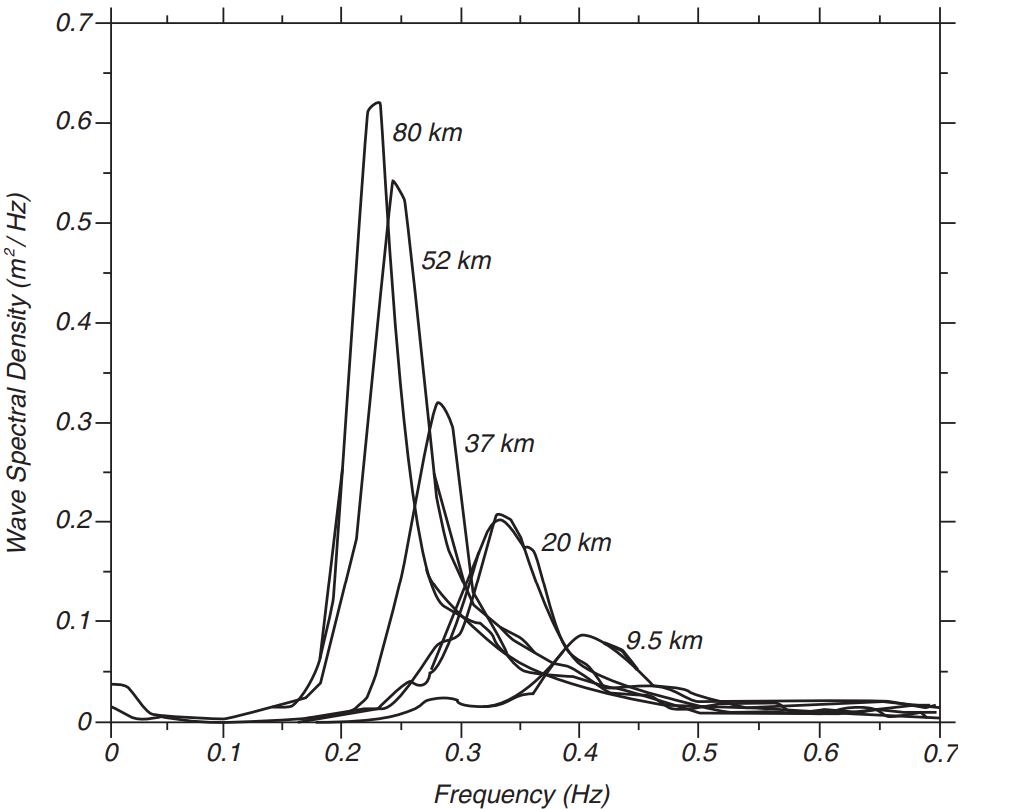

Hasselmann et al. (1973), after analyzing data collected during the Joint North Sea Wave Observation Project JONSWAP, found that the wave spectrum is never fully developed (figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). It continues to develop through non-linear, wave-wave interactions even for very long times and distances. They therefore proposed the spectrum:

\[\begin{array}{c} S(\omega) = \dfrac{\alpha g^{2}}{\omega^{5}} \exp \left[-\dfrac{5}{4} \left(\dfrac{\omega_{p}}{\omega}\right)^{4}\right] \gamma^{r} \\ r = \exp \left[- \dfrac{\left(\omega - \omega_{p}\right)^{2}}{2 \sigma^{2} \omega_{p}^{2}}\right] \end{array} \nonumber \]

Wave data collected during the JONSWAP experiment were used to determine the values for the constants in \((\PageIndex{7})\): \[\begin{array}{c} \alpha = 0.076 \left(\dfrac{U_{10}^{2}}{F \ g}\right)^{0.22} \\ \omega_{p} = 22 \left(\dfrac{g^{2}}{U_{10} F}\right)^{1/3} \\[4pt] \gamma = 3.3 \\[4pt] \sigma = \begin{cases} 0.07 \quad \omega \leq \omega_{p} \\ 0.09 \quad \omega > \omega_{p} \end{cases} \end{array} \nonumber \]

where \(F\) is the distance from a lee shore, called the fetch, or the distance over which the wind blows with constant velocity.

The energy of the waves increases with fetch: \[\langle \zeta^{2} \rangle = 1.67 \times 10^{-7} \frac{\left(U_{10}\right)^{2}}{g} F \nonumber \]where \(F\) is fetch.

The JONSWAP spectrum is similar to the Pierson-Moskowitz spectrum, except that waves continues to grow with distance (or time) as specified by the \(\alpha\) term, and the peak in the spectrum is more pronounced, as specified by the \(\gamma\) term. The latter turns out to be particularly important because it leads to enhanced non-linear interactions and a spectrum that changes in time according to the theory of Hasselmann (1966).

Generation of Waves by Wind

We have seen in the last few paragraphs that waves are related to the wind. We have, however, put off until now just how they are generated by the wind. Suppose we begin with a mirror-smooth sea (Beaufort Number 0). What happens if the wind suddenly begins to blow steadily at, say, 8 m/s? Three different physical processes begin:

- The turbulence in the wind produces random pressure fluctuations at the sea surface, which produces small waves with wavelengths of a few centimeters (Phillips, 1957).

- Next, the wind acts on the small waves, causing them to become larger. Wind blowing over the wave produces pressure differences along the wave profile, causing the wave to grow. The process is unstable because, as the wave gets bigger, the pressure differences get bigger, and the wave grows faster. The instability causes the wave to grow exponentially (Miles, 1957).

- Finally, the waves begin to interact among themselves to produce longer waves (Hasselmann et al. 1973). The interaction transfers wave energy from short waves generated by Miles’ mechanism to waves with frequencies slightly lower than the frequency of waves at the peak of the spectrum. Eventually, this leads to waves going faster than the wind, as noted by Pierson and Moskowitz.