16.3: Fossil Fuels

- Page ID

- 6945

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\) Staplegunther at the English language Wikipedia [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons" width="462px" height="289px" src="/@api/deki/files/7594/16.2_Castle_Gate_Power_Plant_Utah_2007-300x188.jpg">

Staplegunther at the English language Wikipedia [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons" width="462px" height="289px" src="/@api/deki/files/7594/16.2_Castle_Gate_Power_Plant_Utah_2007-300x188.jpg">Fossils fuels are extractable sources of stored energy created by ancient ecosystems. The natural resources that typically fall under this category are coal, oil (petroleum), and natural gas. This energy was originally formed via photosynthesis by living organisms such as plants, phytoplankton, algae, and cyanobacteria. Sometimes this is known as fossil solar energy since the energy of the sun in the past has been converted into the chemical energy within a fossil fuel. Of course, as the energy is used, just like respiration from photosynthesis that occurs today, carbon can enter the atmosphere, causing climate consequences (see ch. 15). Fossil fuels account for a large portion of the energy used in the world.

CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons" width="300" src="/@api/deki/files/7592/Coral_Outcrop_Flynn_Reef-300x225.jpg">

CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons" width="300" src="/@api/deki/files/7592/Coral_Outcrop_Flynn_Reef-300x225.jpg">The conversion of living organisms into hydrocarbon fossil fuels is a complex process. As organisms die, decomposition is hindered, usually due to rapid burial, and the chemical energy within the organisms’ tissues is added to surrounding geologic materials. Higher productivity in the ancient environment leads to a higher potential for fossil fuel accumulation, and there is some evidence of higher global biomass and productivity over geologic time [8]. Lack of oxygen and moderate temperatures seem to enhance the preservation of these organic substances [9; 10]. Heat and pressure that is applied after burial also can cause transformation into higher quality materials (brown coal to anthracite, oil to gas) and/or migration of mobile materials [11].

Oil and Gas

Petroleum, with the liquid component commonly called oil and gas component called natural gas (mostly made up of methane), is principally derived from organic-rich shallow marine sedimentary deposits [12]. As the rock (which is typically shale, mudstone, or limestone) lithifies, the oil and gas leak out of the source rock due to the increased pressure and temperature, and migrate to a different rock unit higher in the rock column. Similar to the discussion of good aquifers in chapter 11, if the rock is sandstone, limestone, or other porous and permeable rock, then that rock can act as a reservoir for the oil and gas.

GFDL or CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons" width="384px" height="248px" src="/@api/deki/files/7593/Structural_Trap_Anticlinal.svg_-300x194.png">

GFDL or CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons" width="384px" height="248px" src="/@api/deki/files/7593/Structural_Trap_Anticlinal.svg_-300x194.png">A trap is a combination of a subsurface geologic structure and an impervious layer that helps block the movement of oil and gas and concentrates it for later human extraction [13; 14]. The development of a trap could be a result of many different geologic situations. Common examples include an anticline or domal structure, an impermeable salt dome, or a fault-bounded stratigraphic block (porous rock next to non-porous rock). The different traps have one thing in common: they pool the fluid fossil fuels into a configuration in which extraction is more likely to be profitable. Oil or gas in strata outside of a trap renders extraction is less viable.

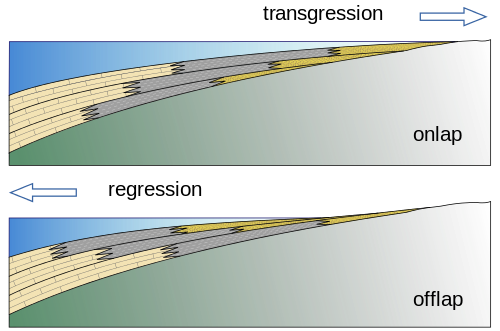

A branch of geology that has grown from the desire to understand how changing sea level creates organic-rich shallow marine muds, carbonates, and sands in close proximity to each other are called sequence stratigraphy [15]. A typical shoreline environment has beaches next to lagoons next to coral reefs. Layers of beach sands and lagoonal muds and coral reefs accumulate into sediments that form sandstones, good reservoir rocks, next to mudstones next to limestones, both potential source rocks. As sea level either rises or falls, the location of the shoreline changes and the locations of sands, muds, and reefs with it. This places oil and gas producing rocks (like mudstones and limestones) next to oil and gas reservoirs (sandstones and some limestones). Understanding the interplay of lithology and ocean depth can be very important in finding new petroleum resources because using sequence stratigraphy as a model can allow predictions to be made about the locations of source rocks and reservoirs.

Tar Sands

CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons" width="308px" height="294px" src="/@api/deki/files/7601/Tar_Sandstone_California-300x286.jpg">

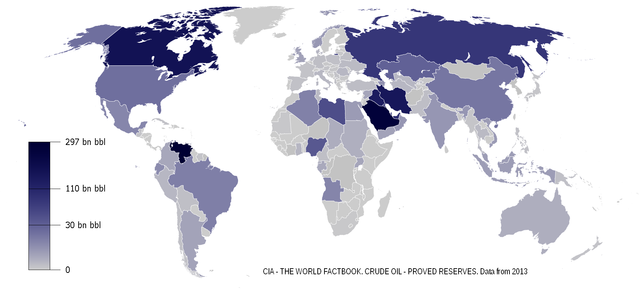

CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons" width="308px" height="294px" src="/@api/deki/files/7601/Tar_Sandstone_California-300x286.jpg">Conventional oil and gas (pumped from a reservoir) are not the only way to obtain hydrocarbons. The next few sections are known as unconventional petroleum sources, though, they are becoming more important as conventional sources increase in scarcity. Tar sands, or oil sands, are sandstones that contain petroleum products that are highly viscous (like tar), and thus, can not be drilled and pumped out of the ground, unlike conventional oil. The fossil fuel in question is bitumen, which can be pumped as a fluid only at very low rates of recovery and only when heated or mixed with solvents. Thus injections of steam and solvents, or direct mining of the tar sands for later processing can be used to extract the tar from the sands. Alberta, Canada is known to have the largest reserves of tar sands in the world [16].

An energy resource becomes uneconomic once the total cost of extracting it exceeds the revenue which is obtained from the sale of extracted material

Oil Shale

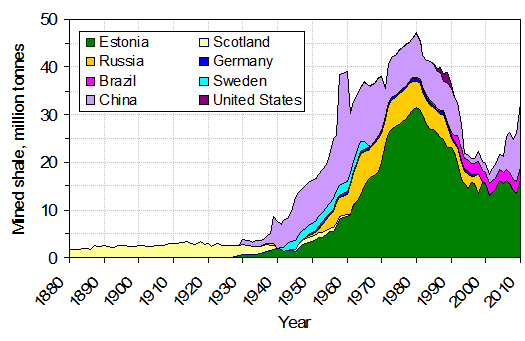

Oil shale (or tight oil) is a fine-grained sedimentary rock that has a significant quantity of petroleum or natural gas. Shale is a common source of fossil fuels with high porosity but it has very low permeability. In order to get the oil out, the material has to be mined and heated, which, like with tar sands, is expensive and typically has a negative impact on the environment [17].

Fracking

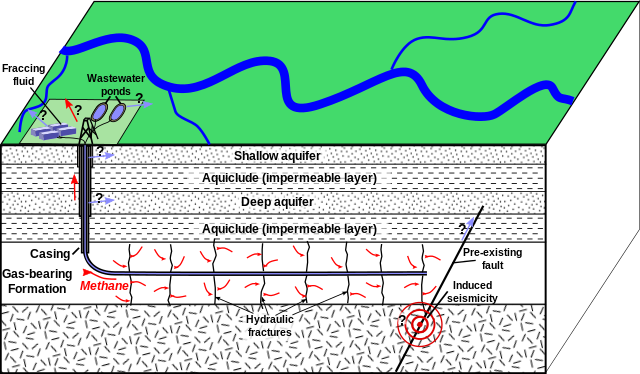

Another process which is used to extract the oil and gas from shale and other unconventional tight resources is called hydraulic fracturing, better known as fracking [18]. In this method, high-pressure injections of water, sand grains, and added chemicals are pumped underground, creating and holding open fractures in the rocks, which aids in the release of the hard-to-access fluids, mostly natural gas. This is more useful in tighter sediments, especially shale, which has a high porosity to store the hydrocarbons but low permeability to transmit the hydrocarbons. Fracking has become controversial due to the potential for groundwater contamination [19] and induced seismicity [20] and represents a balance between public concerns and energy value.

Coal

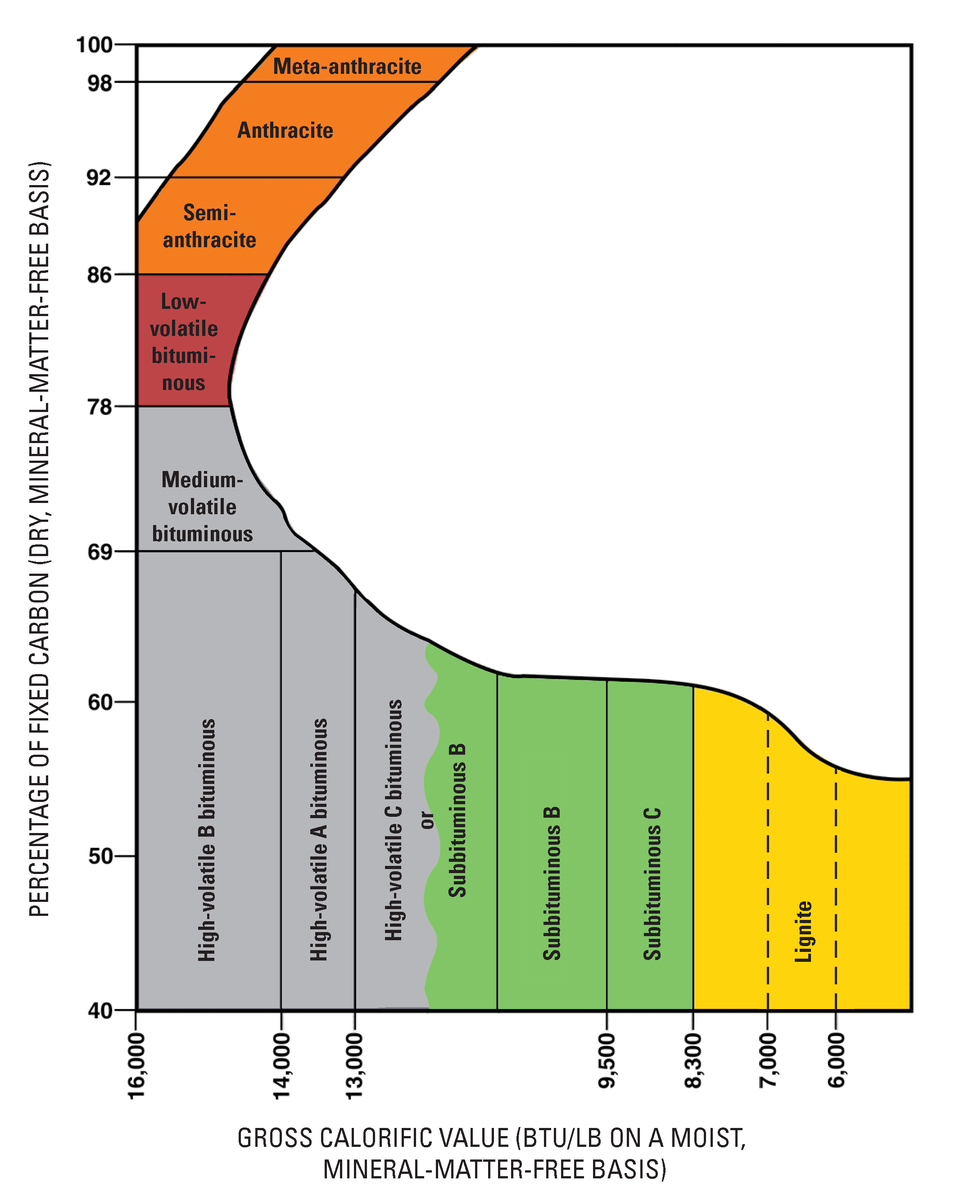

Coal is the product of fossilized swamps [21], though some older coal deposits that predate terrestrial plants are presumed to come from algal buildups [22]. It is chiefly carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen, with minor amounts of other elements [23]. As this plant material is incorporated into sediments, it undergoes a series of changes due to heat and pressure which concentrates fixed carbon, the combustible portion of the coal. In this sense, the more heat and pressure that coal undergoes, the greater is its fuel value and the more desirable is the coal. The general sequence of a swamp turning into the various stages of coal are:

Swamp => Peat => Lignite => Sub-bituminous => Bituminous => Anthracite => Graphite.

As swamp materials collect on the floor of the swamp, they turn to peat. As lithification occurs, peat turns to lignite. With increasing heat and pressure, lignite turns to sub-bituminous coal, bituminous coal, and then, in a process like metamorphism, anthracite. Anthracite is the highest metamorphic grade and most desirable coal since it provides the highest energy output. With even more heat and pressure driving out all the volatiles and leaving pure carbon, anthracite can turn to graphite.

![USGS [Public domain], <a data-cke-saved-href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACoal_anthracite.jpg" href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACoal_anthracite.jpg" It is very black and shiny.](http://opengeology.org/textbook/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Coal_anthracite-300x281.jpg) via Wikimedia Commons" width="300" src="/@api/deki/files/7604/Coal_anthracite-300x281.jpg">

via Wikimedia Commons" width="300" src="/@api/deki/files/7604/Coal_anthracite-300x281.jpg">Coal has been used by humans for at least 6000 years [23], mainly as a fuel source. Coal resources in Wales are often cited as a primary reason for the rise of Britain (and later, the United States) in the Industrial Revolution [24; 25; 26]. According to the US Energy Information Administration, the production of coal in the US has decreased due to cheaper prices of competing for energy sources and recognition of its negative environmental impacts, including increased very fine-grained particulate matter, greenhouse gases [27], acid rain [28], and heavy metal pollution [29]. Seen from this point of view, the coal industry is unlikely to revive.

References

9. Gordon, M., Jr, Tracey, J. I., Jr & Ellis, M. W. Geology of the Arkansas bauxite region. (1958).

12. Pratt, W. E. Oil in the Earth. (University of Kansas Press, 1942).

14. Dott, R. H. & Reynolds, M. J. Sourcebook for petroleum geology. (1969).

16. Bauquis, P.-R. What future for extra heavy oil and bitumen: the Orinoco case. in 13, 18 (1998).

17. Youngquist, W. Shale oil--The elusive energy. Hubbert Center Newsletter 4, (1998).

24. Belloc, H. The Servile State. (T.N. Foulis, 1913).

25. McKenzie, H. & Moore, B. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. (1970).