8.6.3: Tornadoes

- Page ID

- 16082

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Tornadoes

Tornadoes are the most powerful weather phenomenon known. A tornado is an intense system of low pressure with violent updrafts and converging winds. Though tornadoes have been intensely studied for years, the mechanism that actually creates them still eludes us. Tornadoes have been documented in most all the regions of the Earth, though they are most prevalent in the United States.

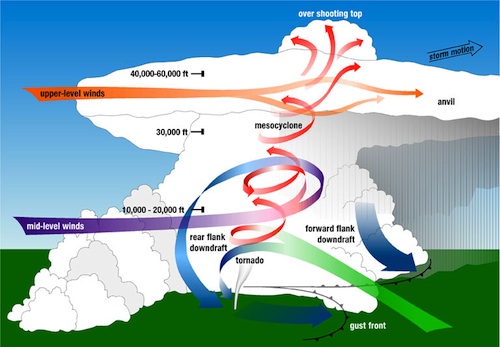

Tornadoes are spawned from severe thunderstorms. Wind shear, where winds are traveling at different speeds and from different directions aloft cause rotation of air about a horizontal axis within the thunderstorm. The rotating circulation is tilted into the vertical by the updrafts of air in a severe thunderstorm. As the rotating air increases in height and shrinks in size a mesocyclone is formed. For whatever reason, a tornado funnel is spawned within the mesocyclone.

The funnel can remain aloft, twisting and turning without wreaking much havoc below, but is most destructive when it touches the ground. A tornado can vary in diameter from a few hundred feet to greater than a mile. Tornadoes typically move across the surface at speeds ranging from 22 - 33 mph (10 - 15 meters per second). [![]() Watch "Hunt for the Supertwister from PBS].

Watch "Hunt for the Supertwister from PBS].

Tornadoes that develop over water are called waterspouts. Waterspouts my orignate over water or a tornado passes from land to water. View the video "Watersputs" for more.

Video: "Waterspouts". (Courtesy of NOAA)

The central U.S. contains a unique mix of topography and weather factors that combine to create these ferocious weather systems. The most favorable situation for these storms to develop is during the months of April through June when there is the most contrast between air masses in the central United States. The region of highest concentration is that of "tornado alley", a region that stretches from eastern Nebraska through central Kansas and Oklahoma in to the panhandle of Texas. The tornado season varies with latitude, with the southeastern U.S. season from January through March and the north central states during July through September. On April 3, 1974 148 tornadoes struck 13 states leaving a swath of death and destruction across the U.S.

Tornadoes are categorized on the basis of their destruction by the Enhanced Fujita scale. The scale assigns a tornado a 'rating' based on estimated wind speeds and related damage. Several damage indicators, e.g., trees, motels, strip malls are used to estimate wind speeds and classify the tornado. In the May 24, 2013 NPR Talk of the Nation segment "Tracking Killer Tornadoes" , Marshall Shepherd, the president of the American Meteorological Society, describes the ingredients of major tornadoes, and how they are predicted.

Video: Get inside a tornado. (Courtesy of National Geographic)

Learn more about the destructive effect of tornadoes by "Digging Deeper: The April 27, 2011 Southern USA Tornado Outbreak".

April 27-28, 2011 the southeastern United States was struck by an estimated 211 tornadoes. Wreaking havoc over eight states, more than 340 people lost their lives as whole towns were destroyed across Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. It was the most deadly day since March 18, 1925 when 747 people died.

Video: GOES satellite image animation. (Courtesy NASA Earth Observatory)

The perfect conditions for tornado development were closely monitored by the National Weather Service days prior to the events of April 27-28. Warm, moist air at the surface streamed ashore from the Gulf of Mexico. With cold air aloft, highly unstable atmospheric conditions ahead of a strong cold front sweeping drier air behind it. A strong westerly jet stream aloft combined with surface winds from the south and east triggered strong vertical wind shear providing lift to the air. Using composite indices based on these conditions, NOAA's Storm Prediction center issued a "high risk" alert for tornadic conditions more than 12 hours in advance. Beginning in the afternoon of the 26th, thunderstorms exploded in the unstable air. The National Weather Service's worst nightmare was about to come true.

Video: April 27, 2011 Tornado Outbreak (Courtesy NOAA Weather Partners Video Library)Across the southern United States roared a storm system producing some of the largest tornadoes on earth, supertwisters. A rare EF-5 tornado a half mile wide ripped through the community of Smithville, Mississippi at 3:44 pm on the April 27. With estimated peak winds of 205 mph, dozens of homes and businesses were pulled from their foundations. The town's water system was destroyed. Most trees were broken, twisted and stripped of their bark. A second F5 tornado touched down near Hackleburg, Alabama. It was the first time since 1990 that two F5 supertwisters formed on the same day.

Barely a month later, Joplin Missouri was struck by a multi-vortex EF5 tornado on May 22, 201. Estimated at 1.21 km (.75 miles) wide, as it tracked at least 11 km (7 miles) across the city. With winds over 200 mph. Over 125 people were killed and hundreds injured making it the deadliest since modern records have been kept and the eighth-deadliest single tornado in U.S. history.