13: Sedimentary Basins

- Page ID

- 38102

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Sedimentary basins are extremely important geological features because they are long-lived subsiding areas that were able to accumulate thick successions of sediment and sedimentary rock. Basin fills record the interactions of tectonics, climate, biological and surficial processes and are thus important archives of Earth’s history that record information about ancient environments, paleoclimate, sea-level history, tectonics, and the dynamics of ancient ecosystems.

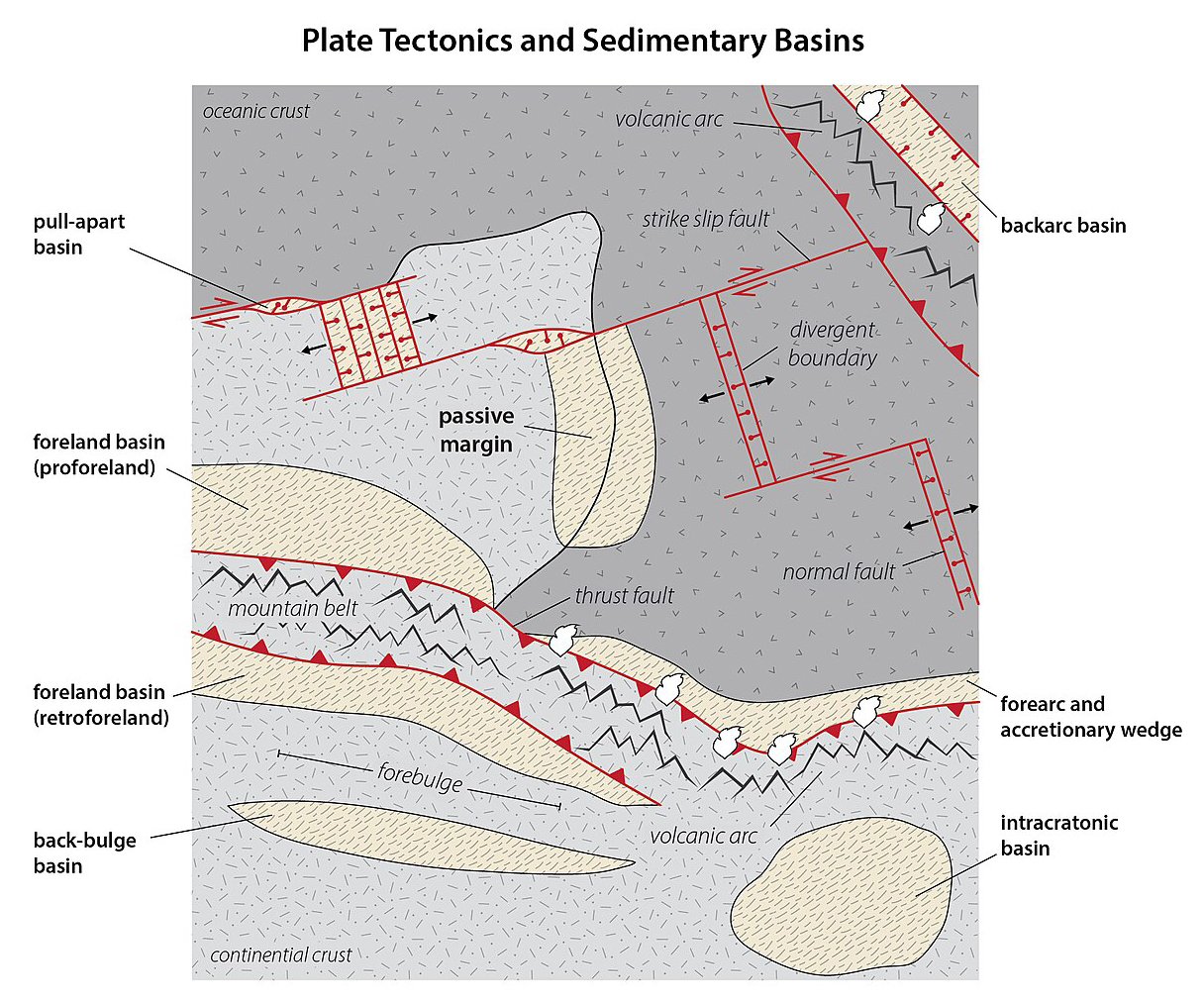

In the following sections, we describe the most common/important types of sedimentary basins using the approach of Allen and Allen (2005), who organized them into three bins according to the tectonic processes responsible for their creation:

- Basins formed by crustal extension

- Basins caused by crustal flexure

- Basins caused by strike slip faulting

Crustal dynamics control the basin’s size, subsidence history, geometry, and stratigraphic architecture and the resulting sedimentary record can be used to interpret these variables.

Sedimentary basins are of great economic importance because they host nearly all fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal), economic minerals (evaporites, phosphorites, etc.), and may be significant aquifers and sources of geothermal energy (especially in extensional settings).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Map showing the relationship between plate tectonics and sedimentary basins (Page Quinton via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0 which is after Sedimentary Basins and Ingersoll, 1988).

- Characterize the tectonic processes that are responsible for the major types of sedimentary basins

- Describe the broad sedimentological patterns that characterize the major types of sedimentary basins

References and Resources

-

Allen, P.A., and Allen, J.R. Basin Analysis: Principles and Application to Petroleum Play Assessment: Wiley-Blackwell, 640 p.

-

Ingersoll, R., 1988, Tectonics of sedimentary basins: GSA Bulletin, v. 100, p. 1704–1719.

- 13.1: Review of Plate Tectonics

- This page outlines the transition from "continental drift" to plate tectonics, emphasizing the movement of tectonic plates over the asthenosphere and their interactions at various boundaries. It details types of boundaries, including convergent and transform, and discusses the formation of mountains and volcanic activity during plate collisions.

- 13.2: Basins Formed by Crustal Extension and/or Thermal Sag

- This page discusses the formation and characteristics of rift basins in extensional tectonic settings, outlining their development phases and related geological features like passive margins. It also covers intracratonic basins, which arise within continental cratons, emphasizing their gradual subsidence, symmetrical morphology, and sediment deposition influenced more by climatic factors than tectonics.

- 13.3: Basins Caused by Crustal Loading and/or Flexure

- This page discusses the formation and characteristics of foreland basins due to crustal shortening in convergent plate tectonics, detailing their types, sedimentary structures, and the transition from deep-water "flysch" to shallow "molasse" deposits. It also covers accretionary wedges and forearc basins at subduction zones, highlighting their dynamics and composition. The page emphasizes the influence of tectonic activity on sedimentary processes and basin morphology.

- 13.4: Basins Caused by Strike-Slip Faulting

- This page discusses strike-slip basins that form due to horizontal movement along faults, resulting in localized crustal extensions or compressions. These basins usually appear where faults bend and can collect thick coarse-grained sediment during tectonic activity, while finer sediments may develop when inactive. Volcanism is uncommon due to minimal crustal thinning, and the shape and behavior of these basins are influenced by local fault geometry.

Chapter thumbnail shows the fill of a rift basin (Page Quinton via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0).