5.3: Mudrocks

- Page ID

- 26414

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

By definition, mudrocks contain more than 50% mud-sized particles (silt and clay). They are the most abundant sedimentary rocks because the sediment typically is deposited in calm environments relatively far from tectonically-active areas. Although they commonly contain abundant organic material and are important source rocks in petroleum systems, they are understudied because they weather quickly and are generally not well exposed at the surface and because specialized techniques and equipment are needed to fully understand the fine-grained particles that make up these rocks.

Mudrock Classification

Unfortunately, there is no one universally accepted classification scheme for mudrocks. We use the term mudrock to refer to all rocks containing >50% clay and silt. If further subdivision is required, we use the terms siltstone (<33% clay), mudstone (33-67% clay), and claystone (>67% clay).

We use the term shale to describe a mudrock that has pronounced fissility (breaks into sheets); this takes the place of terms like mudrock, siltstone, mudstone, and claystone. Modifiers like sandy, pebbly, etc. are useful in some situations.

Important Properties

Stratification and Weathering

The outcrop appearance of a mudrock reflects some combination of resistance to weathering and nature of primary stratification. Adjectives like shale, platy (flattened), blocky (equant), hackly (equant with sharp edges), etc. are very useful when describing mudrocks in outcrop.

Color

If its primary and reflects the characteristics of the sediment at the time of deposition, the color of a mudrock can tell your something about the organic content and amount of oxygen in the system when the sediment was deposited. Red mudrocks reflect very little organic material and abundant oxygen in the system at the time of deposition; many are deposited in terrestrial environments. Green/gray color reflects reducing conditions with a modest amount of organic material; these conditions exist in a variety of environments. Black mudrocks have abundant organic material and record anoxic conditions at the time of deposition; these sorts of conditions can occur in a variety of environments from oxbow lakes on a floodplain to deep marine sediments.

Mudrocks can form anywhere there are calm waters. Understanding how and where they formed is facilitated by comparing the physical characteristics described above with characteristics like context, fossil content, color, and detailed analysis of mineralogy and geochemistry (especially of organic components).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Diagram showing the relationship between mudrock color, organic content, and oxidation state of iron. Colors and names are consistent with the Munsell Rock Color Chart. Diagram is after Potter et al. (1980). From Michael C. Rygel via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0.

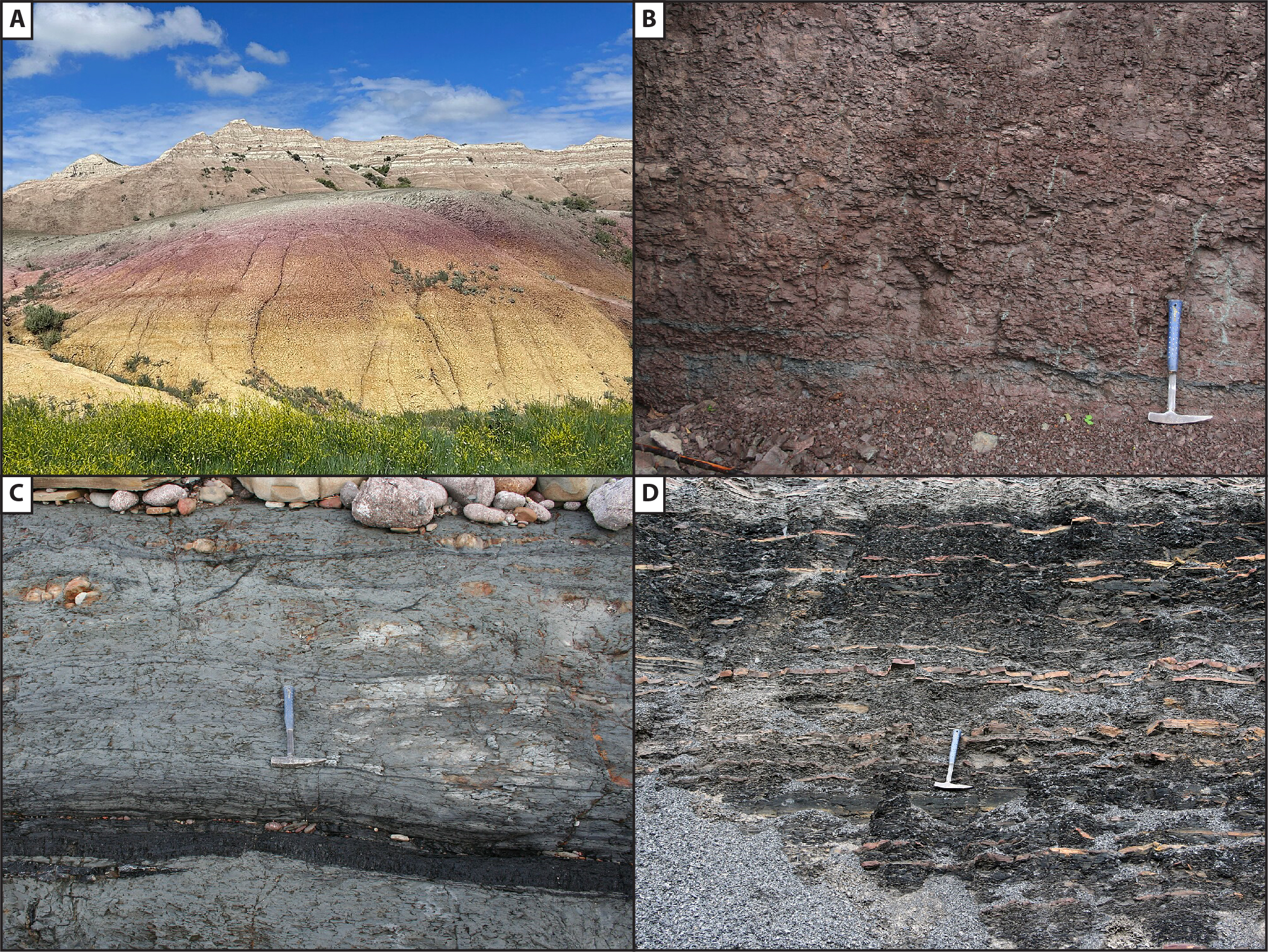

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Mudrock colors and textures. A) Bright yellow, red, and/or purple colors are commonly associated with paleosols (James St. John via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY 2.0). B) The blocky texture and red/green colors of this mudrock suggest that it is a poorly developed paleosol that formed in mostly oxidizing conditions. C) Internally massive greenish gray mudrock with siderite nodules and associated coal; together these features suggest deposition in a reducing swampy environment. D) Platy dark gray to black shales with minor siltstone and sandstones. These rocks likely formed in an organic-rich standing body of water. B-D from Michael C. Rygel via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Mudrock colors and textures. A) Bright yellow, red, and/or purple colors are commonly associated with paleosols (James St. John via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY 2.0). B) The blocky texture and red/green colors of this mudrock suggest that it is a poorly developed paleosol that formed in mostly oxidizing conditions. C) Internally massive greenish gray mudrock with siderite nodules and associated coal; together these features suggest deposition in a reducing swampy environment. D) Platy dark gray to black shales with minor siltstone and sandstones. These rocks likely formed in an organic-rich standing body of water. B-D from Michael C. Rygel via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0.

Components

Mudrocks are composted of silt-sized particles that are typically composed of quartz, feldspar, or other common minerals … some might even be large enough to classify using the petrographic microscope. Larger ones can even be classified with the petrographic microscope.

Although the terminology is confusing, many of the clay-sized particles (<1/256 mm) in a mudrock happen to be “clay minerals” which is a name applied to a specific group of aluminosilicate and phyllosilicates minerals. These clay minerals are derived from weathering (hydrolysis) of feldspar and mica.

Mineralogy

Clay minerals are made of alternating layers of silicon-oxygen tetrahedra (tetrahedral sheets) and alumina-oxygen octahedra (octahedral sheets). These sheets can be layered in a variety of ways and may even alternate with interlayer cations or water. Clay minerals can be grouped into two main families: 2:1 clay minerals and 2:1 clay minerals.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Overview of the major types of clay minerals in sedimentary rocks (Page Quinton via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0). Diagram after Kumari and Mohan (2021).

1:1 clay minerals are the product of more intense/prolonged weathering that progressively strips interlayer cations from 2:1 clay minerals which concentrates Si, Fe, and Al in a simpler structure. Their fundamental building block is a single octahedral layer bonded to a single tetrahedral layer. Kaolinite is probably the best known and most important 1:1 clay mineral because of its close association with alumina-rich soils (bauxites & laterites)

The fundamental building block of 2:1 clay minerals is an octahedral sheet sandwiched between two tetrahedral sheets. Between these T-O-T packages, variable amounts of Al, Mg, Fe, water, or other interlayer cations determine the mineralogy of the specimen. These relatively complex clay minerals tend to form in temperate areas. Noteworthy 2:1 clay minerals include:

- “Swelling clays” like montmorillonite and vermiculite are 2:1 clays that can retain significant amounts of water

- Glauconite is a green, iron-rich clay mineral that forms as a replacement of fecal pellets in reducing marine conditions

- Bentonite is a 2:1 clay formed by weathered volcanic ash beds by alkaline & acidic water, respectively. Given their volcanic origin, dateable minerals like zircon are found with bentonites.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Noteworthy clay minerals. A) Granule-sized Silurian glauconite pellets from Ohio (James Cheshire via Wikimedia Commons; public domain) B) Black shales and bentonites from the Cretaceous Benton Shale (James St. John via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY 2.0). C) White pellets of vermiculite are commonly added to potting soil to help retain water (M Tullottes via Wikimedia Commons; public domain). D) Bag of bentonite a swelling clay that is commonly used to seal well casings (Corey872 via Wikimedia Commons; public domain). E) Kaolinite and, to a lesser degree, montmorillonite and bentonite, are commonly used in pottery clay (Knecht03 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 3.0). Laterites are soils that are enriched in kaolinite and iron via intense tropical weathering; they are commonly used as brick and road bed material (Vinayaraj via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Noteworthy clay minerals. A) Granule-sized Silurian glauconite pellets from Ohio (James Cheshire via Wikimedia Commons; public domain) B) Black shales and bentonites from the Cretaceous Benton Shale (James St. John via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY 2.0). C) White pellets of vermiculite are commonly added to potting soil to help retain water (M Tullottes via Wikimedia Commons; public domain). D) Bag of bentonite a swelling clay that is commonly used to seal well casings (Corey872 via Wikimedia Commons; public domain). E) Kaolinite and, to a lesser degree, montmorillonite and bentonite, are commonly used in pottery clay (Knecht03 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 3.0). Laterites are soils that are enriched in kaolinite and iron via intense tropical weathering; they are commonly used as brick and road bed material (Vinayaraj via Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 4.0).

Additional Readings and Resources

- Kumari and Mohan, 2021, Basics of Clay Minerals and Their Characteristic Properties

- Potter et al., 1980, Sedimentology of Shale, Springer-Verlag, New York, 306 p., ISBN 0-387-90430-1