1.1: Ecosystems and Humans

- Page ID

- 11687

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define environmental science and distinguish it from related fields such as environmental studies, ecology, and geography.

- Identify key principles of the ecosystem approach to conserving natural resources.

- Describe how environmental stressors and disturbances can affect species and ecosystems.

- List at least three ways in which humans directly influence environmental conditions.

- Identify four broad classes of environmental values.

- Describe five important world views.

- Understand the diverse issues of the environmental crisis by classifying them into three categories, and give several examples within each of them.

- Discuss the environmental effects of humans as a function of two major influences: increases of population and intensification of lifestyle (per-capita effects).

- Explain the differences between economic growth and ecologically sustainable development.

Environmental Science and Its Context

Every one of us is sustained by various kinds of natural resources – such as food, materials, and energy that are harvested or otherwise extracted from the environment. Our need for those resources is absolute – we cannot survive without them.

Collectively, the needs and activities of people comprise a human economy. That economy operates at various scales, ranging from an individual person, to a family, to communities such as towns and cities, countries, and ultimately the global human enterprise. While an enormous (and rapidly growing) number of people are supported by the global economy, a lot of environmental damage is also being caused. The most important of the damages are the depletion of vital natural resources, various kinds of pollution (including climate change), and widespread destruction of natural habitats to the extent that the survival of many of the natural ecosystems and species of Earth are at grave risk.

These issues are of vital importance to all people, and to all life on the planet. Their subject matter provides the context for a wide-ranging field of knowledge called environmental studies, an extremely broad discipline that examines the scientific, social, and cultural aspects of environmental issues. As such, the subject matter of environmental studies engages all forms of inquiry that are relevant to identifying, understanding, and resolving environmental problems. Within that context, environmental science examines the science-related implications of environmental issues (this is explained in more detail in the following section). The subject matter of environmental science is the focus of this book.

Issues related to environmental problems are extremely diverse and they interact in myriad ways. Despite this complexity, environmental issues can be studied by aggregating them into three broad categories:

- the causes and consequences of the rapidly increasing human population

- the use and depletion of natural resources

- damage caused by pollution and disturbances, including the endangerment of biodiversity

These are extremely big issues – their sustainable resolution poses great challenges to people and their economy at all scales. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the study of environmental issues should not be regarded as being a gloomy task of understanding awful problems – rather, the major goal is to identify problems and find practical ways to repair them and prevent others from occurring. These are worthwhile and necessary actions that represent real progress towards an ecologically sustainable economy. As such, people who understand and work towards the resolution of environmental problems can achieve high levels of satisfaction with their contribution. Environmental literacy, which can be defined as an understanding and appreciation of the natural world and the relationship that humans have with it, is a matter of empowerment because it enables people to take control of the condition of the environment.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\):Planet Earth. Earth is the third closest planet to the Sun, and it is the only place in the universe that is definitely known to sustain life and ecosystems. Other than sunlight, the natural resources needed to sustain the human economy are restricted to the limited amounts that can be extracted on Earth. This image of the Western Hemisphere was taken from a distance of 35-thousand km from the surface of Earth. Source: R. Stöckli, N. El Saleous, and M. Jentoft-Nilsen, NASA GSFC; http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=885

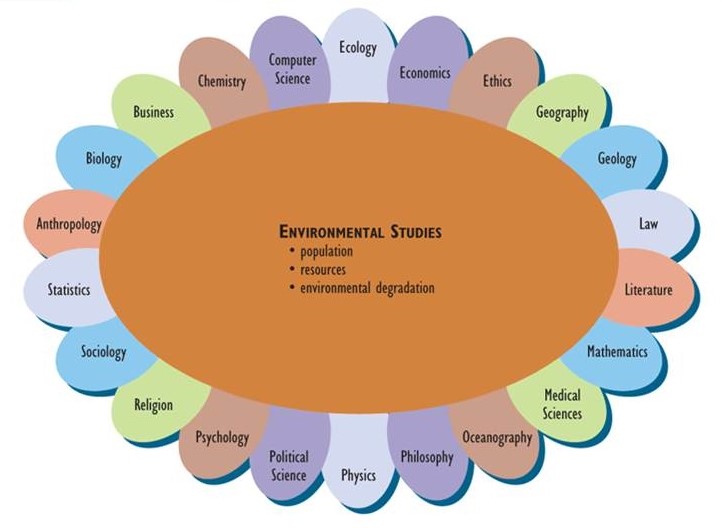

Specialists examining issues related to the environment may come from many different areas of study, each of which is referred to as a discipline. The various contributions each field makes are integrated into a comprehensive understanding of environmental issues – this is why environmental studies is referred to as an interdisciplinary field. For environmental science, the most relevant of the disciplinary subjects are atmospheric science, biology, chemistry, computer science, ecology, geography, geology, mathematics, medical science, oceanography, physics, and statistics. This is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), which suggests that all fields of scientific knowledge are relevant to understanding the causes, consequences, and resolution of environmental problems.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Environmental science has an interdisciplinary character. All scientific disciplines are relevant to the identification and resolution of environmental issues. However, the work requires an interdisciplinary approach that engages many disciplines in a coordinated manner. This integration is suggested by the overlaps among the disciplinary fields.

This book deals with the key subject areas of environmental science. To some degree, however, certain non-science topics are also examined because they are vital to understanding and resolving environmental issues. These non-science fields include ethics, philosophy, political science, and economics.

An environmental scientist is a generalist who uses science-related knowledge relevant to environmental quality, such as air or water chemistry, climate modelling, or the ecological effects of pollution.

It is important to differentiate environmental science from environmentalism, which is advocacy for the environment. The interests of environmentalists may be informed by the work of environmental scientists, but the two groups are not necessarily the same because science is undertaken to gain an understanding of the world and does not include advocacy. Any person can be called an environmentalist if they care about the quality of the environment and work towards changes that would help to resolve the issue. Environmentalists may work as individuals, and they often pursue their advocacy through non-governmental organizations, such as the Sierra Club or The Nature Conservancy.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Modern consumerism results in huge demands for material and energy resources to build and run homes and to manufacture and operate machines and other goods. Source: B. Freedman

Human Activities are Environmental Stressors

These days, ecosystems are impacted by anthropogenic (human-caused) influences that have substantially altered the natural environment. Humans affect ecosystems and species in three direct ways: (a) by harvesting valuable biomass, such as trees and hunted animals; (b) by causing damage through pollution; and (c) by converting natural ecosystems to into land-uses for the purposes of agriculture, industry, or urbanization.

These actions also cause many indirect effects. For example, the harvesting of trees alters the habitat conditions for the diversity of plants, animals, and microorganisms that require forested habitat, thereby affecting their populations. At the same time, timber harvesting indirectly changes functional properties of the landscape, such as erosion, productivity, and the quantity of water flowing in streams. Both the direct and indirect effects of humans on ecosystems are important.

Humans have always left “footprints” in nature – to some degree, they have always influenced the ecosystems of which they were a component. Throughout most of human history, that ecological footprint was relatively shallow. This was because the capability of humans for exploiting their environment was not much different from that of other similarly abundant, large animals. However, during the cultural evolution of humans, the ecological changes associated with our activities progressively intensified. This process of cultural evolution has been characterized by the discovery and use of increasingly more sophisticated methods, tools, and social organizations to secure resources by exploiting the environment and other species.

Certain innovations occurring during the cultural evolution of humans represented particularly large increases in capability. Because of their great influence on human success, these advances are referred to as “revolutions.” The following are the most significant technological revolutions that have enabled humans to have a greater impact on their environment:

- methods of using machines and fossil fuels such as coal and oil (Industrial Revolution)

- discoveries in medicine and sanitation

- advances in agricultural efficiency

These and other revolutionary innovations all led to substantial increases in the ability of humans to exploit the resources of their environment and to achieve population growth. Unfortunately, enhanced exploitation has rarely been accompanied by the development of a compensating ethic that encourages conservation of the resources needed for survival. Even early hunting societies of more than about 10,000 years ago appear to have caused the extinction of species that were hunted too effectively.

The diverse effects of human activities on environmental quality are vital issues, and they will be examined in detail in later chapters. For now, we emphasize the message that intense environmental stress associated with diverse human activities has become the major factor causing ecological changes on Earth. Many of the changes are degrading the ability of the environment and ecosystems to sustain humans and their economies. Anthropogenic activities are also causing enormous damage to natural ecosystems, including to habitats needed to support most other species.

But not all this damage is inevitable. There is sincere hope and expectation that human societies will yet make appropriate adjustments and will choose to pursue options that are more sustainable than many of those now being followed. Environmental science broadens our understanding of our impacts and provides the basis for long-term solutions. Environmental literacy empowers non-scientists with this knowledge.

Ethics and World Views

The choice that people make can influence environmental quality in many ways – by affecting the availability of resources, causing pollution, and causing species and natural ecosystems to become endangered. Decisions influencing environmental quality are influenced by two types of considerations: knowledge and ethics.

In the present context, knowledge refers to information and understanding about the natural world, and ethics refers to the perception of right and wrong and the appropriate behavior of people toward each other, other species, and nature. Of course, people may choose to interact with the environment and ecosystems in various ways. On the one hand, knowledge provides guidance about the consequences of alternative choices, including damage that might be caused and actions that could be taken to avoid that effect. On the other hand, ethics provides guidance about which alternative actions should be favored or even allowed to occur.

Because modern humans have enormous power to utilize and damage the environment, the influence of knowledge and ethics on choices is a vital consideration. And we can choose among various alternatives. For example, individual people can decide whether to have children, purchase an automobile, or eat meat, while society can choose whether to allow the hunting of whales, clear-cutting of forests, or construction of nuclear power plants. All of these options have implications for environmental quality.

Perceptions of value (of merit or importance) also profoundly influence how the consequences of human actions are interpreted. Environmental values can be divided into two broad classes: utilitarian and intrinsic.

-

Utilitarian value (also known as instrumental value) is based on the known importance of something to the welfare of people. Accordingly, components of the environment and ecosystems are considered important only if they are resources necessary to sustain humans—that is, if they bestow economic benefits, provide livelihoods, and contribute to the life-support system. In effect, people harvest materials from nature because they have utilitarian value. These necessities include water, timber, fish and animals hunted in wild places, and agricultural crops grown in managed ecosystems.

Ecological values are somewhat broader utilitarian values—they are based on the needs of humans, but also on those of other species and natural ecosystems. Ecological values often take a longer-term view, valuing ecosystems regardless of their usefulness to humans. Aesthetic values are also utilitarian but are based on an appreciation of beauty. They are subjective and influenced by cultural perspectives. For instance, environmental aesthetics might value natural wilderness over human-dominated ecosystems, free-living whales over whale meat, and large standing trees over toilet paper.

-

Intrinsic value is based on the belief that components of the natural environment (such as species and natural ecosystems) have inherent value and a right to exist, regardless of any positive, negative, or neutral relationships with humans. Under this system, it would be wrong for people to treat other creatures cruelly, to take actions that cause natural entities to become endangered or extinct, or to fail to prevent such occurrences. In effect, by this perception, all species have a right to exist.

As was noted previously, ethics concerns the perception of right and wrong and the values and rules that should govern human conduct. Clearly, ethics of all kinds depend upon the values that people believe are important. Environmental ethics deal with the responsibilities of present humans to both future generations and other species to ensure that the world will continue to function in an ecologically healthy way, and to provide adequate resources and livelihoods. The environmental values described above underlie this system of ethics. Applying environmental ethics often means analyzing and balancing standards that may conflict, because aesthetic, ecological, intrinsic, and utilitarian values rarely all coincide.

There is also tension between ethical considerations that are individualistic and those that are holistic. For example, animal-rights activists are highly concerned with issues involving the treatment of individual organisms. Ecologists, however, are typically more concerned with holistic values, such as a population, species, or ecosystem. As such, an ecologist might advocate a cull of overabundant deer in a park in order to favour the survival of populations of endangered plants, whereas that action might be resisted by an animal-rights activist.

Values and ethics, in turn, support larger systems known as world views. A worldview is a comprehensive philosophy of human life and the universe, and of the relationship between people and the natural world. World views include traditional religions, philosophies, and science, as well as other belief systems. In an environmental context, generally important world views are known as anthropocentric, biocentric, and ecocentric, while the frontier and sustainability world views are more related to the use of resources.

The anthropocentric worldview considers humans as being at the center of moral consideration. People are viewed as being more worthy than any other species and as uniquely disconnected from the rest of nature. Therefore, the anthropocentric worldview judges the importance and worthiness of everything, including other species and ecosystems, in terms of the implications for human welfare.

The biocentric worldview focuses on living entities and considers all species (and individuals) as having intrinsic value. Humans are considered a unique and special species, but not as being more worthy than other species. As such, the biocentric worldview rejects discrimination against other species, or speciesism (a term similar to racism or sexism).

The ecocentric worldview considers the direct and indirect connections among species within ecosystems to be invaluable. It also includes consideration for non-living entities, such as rocks, soil, and water. It incorporates the biocentric worldview but goes well beyond it by stressing the importance of interdependent ecological functions, such as productivity and nutrient cycling.

The frontier worldview asserts that humans have a right to exploit nature by consuming natural resources in boundless quantities. This world view claims that people are superior and have a right to exploit nature. Moreover, the supply of resources to sustain humans is considered to be limitless, because new stocks can always be found, or substitutes discovered. The consumption of resources is considered to be good because it enables economies to grow. Nations and individuals should be allowed to consume resources aggressively, as long as no people are hurt in the process.

The sustainability worldview acknowledges that humans must have access to vital resources, but the exploitation of those necessities should be governed by appropriate ecological, intrinsic, and aesthetic values. The sustainability world view can assume various forms. The spaceship worldview is quite anthropocentric. It focuses only on sustaining resources needed by people, and it assumes that humans can exert a great degree of control over natural processes and can safely pilot “spaceship Earth.” In contrast, ecological sustainability is more ecocentric. It considers people within an ecological context and focuses on sustaining all components of Earth’s life-support system by preventing human actions that would degrade them. In an ecologically sustainable economy, natural goods and services should be utilized only in ways that do not compromise their future availability and do not endanger the survival of species or natural ecosystems.

The attitudes of people and their societies toward other species, natural ecosystems, and resources have enormous implications for environmental quality. Extraordinary damages have been legitimized by attitudes based on a belief in the inalienable right of humans to harvest whatever they desire from nature, without consideration of pollution, threats to species, or the availability of resources for future generations. Clearly, one of the keys to resolving the environmental crisis is to achieve a widespread adoption of ecocentric and ecological sustainability worldviews.

The Environmental Crisis

The modern environmental crisis encompasses many issues. In large part, however, we can classify the issues into three categories: population, resources, and environmental quality. In essence, these topics are what this book is about. However, the core of their subject areas is the following:

-

Population

In 2020, the human population numbered more than 7.8 billion. At the global level, the human population has been increasing because of the excess of birth rates over death rates. The recent explosive population growth, and the poverty of so many people, is a root cause of much of the environmental crisis. Directly or indirectly, large population increases result in extensive deforestation, expanding deserts, land degradation by erosion, shortages of water, change in regional and global climate, endangerment and extinction of species, and other great environmental problems. Considered together, these damages represent changes in the character of the biosphere that are as cataclysmic as major geological events, such as glaciation.

-

Resources

Two kinds of natural resources can be distinguished. A non-renewable resource is present in a finite quantity. As these resources are extracted from the environment, in a process referred to as mining, their stocks are inexorably diminished and so are available in increasingly smaller quantities for future generations. Non-renewable resources include metals and fossil fuels such as petroleum and coal. In contrast, a renewable resource can regenerate after harvesting, and if managed suitably, can provide a supply that is sustainable forever. However, to be renewable, the ability of the resource to regenerate cannot be compromised by excessive harvesting or inappropriate management practices. Examples of renewable resources include fresh water, the biomass of trees and agricultural plants and livestock, and hunted animals such as fish and deer. Ultimately, a sustainable economy must be supported by renewable resources. Too often, however, potentially renewable resources are not used responsibly, which impairs their renewal and represents a type of mining.

-

Environmental Quality

This subject area deals with anthropogenic pollution and disturbances and their effects on people, their economies, other species, and natural ecosystems. Pollution may be caused by gases emitted by power plants and vehicles, pesticides, or heated water discharged into lakes. Examples of disturbance include clear-cutting, overfishing, and forest fires.

Environmental Impacts of Humans

In a general sense, the cumulative impact of humans on the biosphere is a function of two major factors: (1) the size of the population and (2) the per-capita (per-person) environmental impact. The human population varies greatly among and within countries, as does the per-capita impact, which depends on the kind and degree of economic development that has occurred.

One powerful tool for expressing environmental impact is the ecological footprint. This is essentially the amount of land that is required to provide the resources and dispose of the wastes associated with a particular lifestyle. It is estimated based upon various categories of consumption and is useful in comparing the impact that different people have on the planet. Recent calculations using this model suggest that humans are using more than the amount of resources that the earth can sustainably regenerate. When this happens, it is said that we are in an ecological deficit. This means that while we may still be able to extract the resources necessary to support our lifestyles, we are no longer doing so sustainably and as a result, we will not be able to continue indefinitely.

In general, the size of an ecological footprint tends to increase with wealth or affluence. People in wealthy nations tend to have much larger footprints than those in developing countries. As such, lifestyle decisions have a large impact on our overall footprint. The per capita ecological footprint (footprint per person) is one of the highest in the world. But that is only part of the story of overall impact.

Paul Ehrlich, an American ecologist, has expressed this simple relationship using an “impact formula,” as follows: I = P × A × T, where

- I is the total environmental impact of a human population

- P is the population size

- A is an estimate of the per-capita affluence in terms of resource use

- T is the degree of technological development of the economy, on a per-capita basis

As the size of a population increases, so does the overall environmental impact. Similarly, as affluence increases, the impact goes up as well. Technology does not have as direct a relationship because some technologies can be damaging to the environment (widespread use of cars), while others can have a positive impact (wind turnbines).

Calculations based on this simple IPAT formula show that affluent, technological societies have a much larger per-capita environmental impact than do poorer ones.

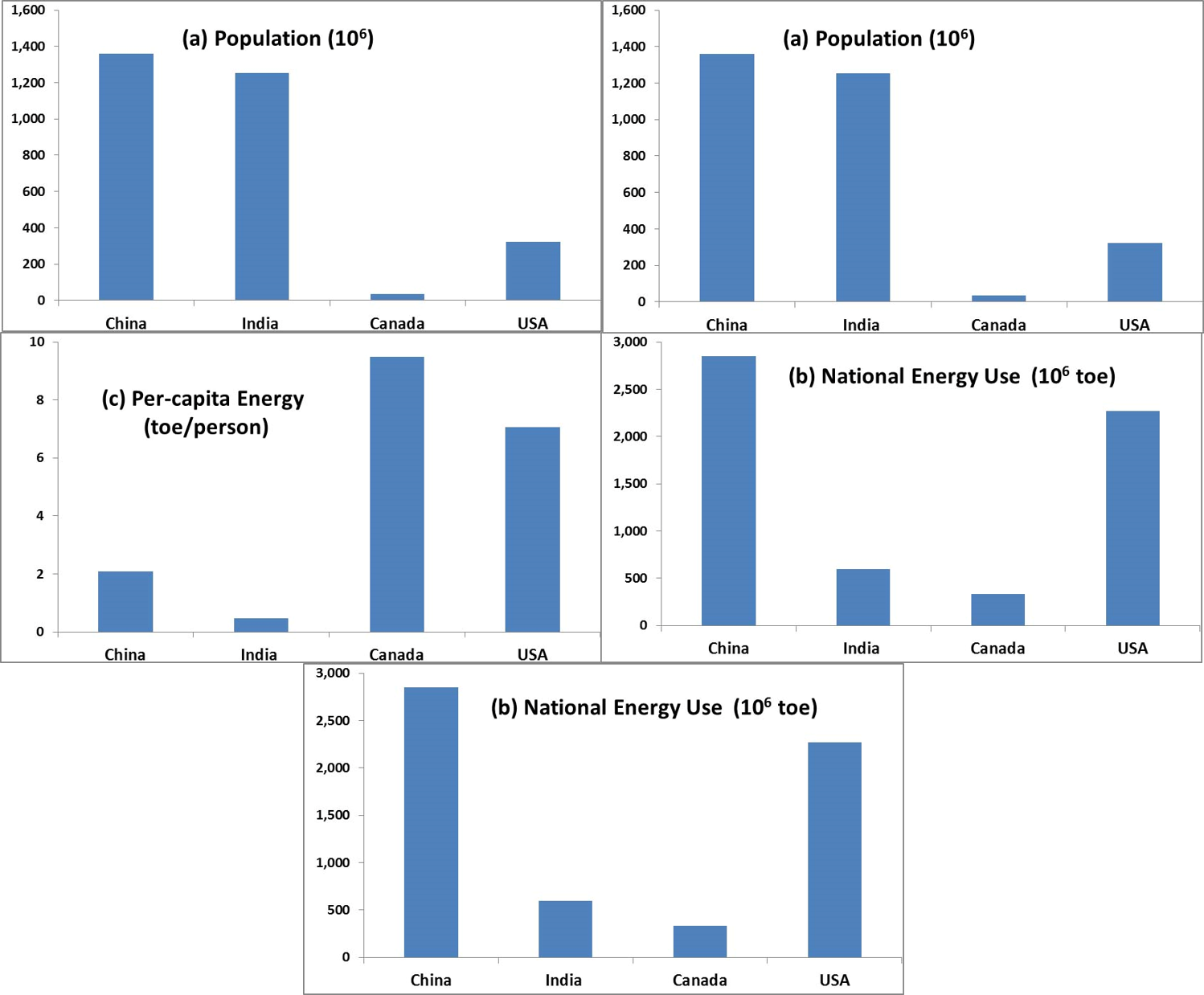

How does the United States’ impact on the environment compare with that of more populous countries, such as China and India? We can examine this question by looking at two simple indicators of the environmental impact of both individual people and national economies: (a) the size of the human population, (b) the use of energy and (c) gross domestic product (GDP, or the annual value of all goods and services produced by a country). The use of energy is a helpful environmental indicator because power is needed to carry out virtually all activities in a modern society, including driving vehicles, heating or cooling buildings, manufacturing industrial products, and running computers. GDP represents all of the economic activities in a country, each of which results in some degree of environmental impact.

One of the major influences on the environmental impact of any human population is the number of people (the population size). In this respect, the US has a much smaller population compared to China, India (Figure 1.3a).

However, on a per-person basis, people living in US or Canada have much larger environmental impacts than do those living in China or India, as indicated by both per-capita energy use (Figure 1.3c) and per-capita GDP (Figure 1.3e). This difference is an inevitable consequence of the prosperous nature of the lifestyle of North Americans and other wealthier people, which on a per-capita basis is achieved by consuming relatively large amounts of natural resources and energy while generating a great deal of waste materials.

However, the per-capita environmental impact is only part of the environmental influence of a country, or of any human population. To determine the national effect, the per-capita value must be multiplied by the size of the population. When this is done for energy, China and the U.S. have by far the largest values, while Canada and India are much less (Figure 1.3b). Still, it is remarkable that the national energy use of Canada, with its relatively small population, is close to that of India and within an order of magnitude of China, which have enormously larger populations. The same pattern is true of national the GDPs of those countries.

These observations drive home the fact that the environmental impact of any human population is a function of both (a) the number of people and (b) the per-person environmental impact. Because of this context, wealthy countries like the US have much larger environmental impacts than might be predicted based only on the size of their population. On the other hand, the environmental impacts of poorer countries are smaller than might be predicted based on their population. We can conclude that the environmental crisis is due to both overpopulation and excessive resource consumption.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). The relative environmental impacts of China, India, Canada, and the United States. The environmental impacts of countries, and of their individual citizens, can be compared using simple indicators, such as the use of energy and the gross domestic product. Canada’s relatively small population, compared with China and India, is somewhat offset by its higher per-capita GDP and use of energy. However, because the per-capita data for the U.S. and Canada are similar, relative population sizes are the key influence on the environmental impacts of these two countries. Sources of data: population data are for 2015 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015); energy use (all commercial fuels) for 2013 (BP, 2013); GDP for 2013 (CIA, 2014).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): The relative environmental impacts of China, India, Canada, and the United States. The environmental impacts of countries, and of their individual citizens, can be compared using simple indicators, such as the use of energy and the gross domestic product. Canada’s relatively small population, compared with China and India, is somewhat offset by its higher per-capita GDP and use of energy. However, because the per-capita data for the U.S. and Canada are similar, relative population sizes are the key influence on the environmental impacts of these two countries. Sources of data: population data are for 2015 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015); energy use (all commercial fuels) for 2013 (BP, 2013); GDP for 2013 (CIA, 2014).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Places where people live, work, grow food, and harvest natural resources are affected by many kinds of anthropogenic stressors. These result in ecosystems that are not very natural in character, such as the pavement and grassy edges of this major highway in Toronto. Source: B. Freedman.

Ecologically Sustainable Development

Sustainable development refers to the development of an economic system that uses natural resources in ways that do not deplete them or otherwise compromise their availability to future generations. In this sense, the present human economy is clearly non-sustainable. The reason for this bold assertion is that the present economy achieves rapid economic growth through vigorous depletion of both non-renewable and renewable resources. Economic growth and development are different phenomena. Economic growth refers to increases in the size of an economy because of expansions of both population and per-capita resource use. This growth is typically achieved by increasing the consumption of natural resources, particularly non-renewable ones such as fossil fuels and metals. The rapid use results in an aggressive depletion of vital non-renewable resources, and even renewable ones.

Almost all national economies have been growing rapidly in recent times. Moreover, most politicians, economic planners, and business people hope for additional growth of economic activity, in order to generate more wealth and to provide a better life for citizens. At the same time, however, most leaders of society have publicly affirmed their support of sustainable development. However, they are confusing sustainable development with “sustainable economic growth.” Unfortunately, continuous economic growth is not sustainable because there are well-known limits due to finite stocks of natural resources, as well as a limited ability of the biosphere to absorb wastes and ecological damage without suffering irreversible degradation. This limit is a fundamental principle of ecological economics (covered later in the text).

Economic development is quite different from economic growth. Development implies a progressively improving efficiency in the use of materials and energy, a process that reflects socio-economic evolution toward a more sustainable economy. Within that context, so-called developed countries have a relatively well-organized economic infrastructure and a high average per-capita income (because of their latter characteristic, they may also be referred to as high-income countries). Examples include the United States, Japan, countries of western Europe, and Australia. In contrast, less-developed or low-income countries have much less economic infrastructure and low per-capita earnings. Examples include Afghanistan, Bolivia, Myanmar, and Zimbabwe. A third group is comprised of rapidly developing or middle-income countries, such as Brazil, Chile, China, India, Malaysia, Russia, and Thailand.

A sustainable economy must be fundamentally supported by the wise use of renewable resources, meaning they are not used more quickly than their rate of regeneration. For these reasons, the term sustainable development should refer only to progress being made toward a sustainable economic system. Progress in sustainable development involves the following sorts of desirable changes:

- increasing efficiency of use of non-renewable resources, for example, by careful recycling of metals and by optimizing the use of energy

- increasing use of renewable sources of energy and materials in the economy (to replace non-renewable sources)

- improving social equity, with the ultimate goal of helping all people (and not just a privileged minority) to have reasonable access to the basic necessities and amenities of life

Despite abundant public rhetoric, our society has not yet made much progress toward true sustainability. This has happened because most actions undertaken by governments and businesses have supported economic growth, rather than sustainable development.

Sustainable development is a lofty and necessary goal for society to pursue. But if a sustainable human economy is not attained, then the non-sustainable one will run short of resources and could collapse. This would cause terrible misery for huge numbers of people and colossal damage to the biosphere.

The notion of sustainability can be further extended to that of ecologically sustainable development. This idea includes the usual aspect of sustainable development in which countries develop without depleting their essential base of natural resources, essentially by basing their economy on the wise use of renewable sources of energy and materials. Beyond that, however, an ecologically sustainable economy runs without causing an irretrievable loss of natural ecosystems or extinctions of species, while also maintaining important environmental services, such as the provision of clean air and water. Ecological sustainability is a reasonable extension of sustainability, which only focuses on the human economy. By expanding to embrace the interests of other species and natural ecosystems, ecological sustainability provides an inclusive vision for a truly harmonious enterprise of humans on planet Earth. Identifying and resolving the barriers to ecological sustainability are the fundamental objectives and subject matter of environmental studies. It provides a framework for all that we do.

Conclusions

Environmental science is a highly interdisciplinary field that is concerned with issues associated with the rapidly increasing human population, the use and diminishing stocks of natural resources, damage caused by pollution and disturbance, and effects on biodiversity and the biosphere. These are extremely important issues, but they involve complex and poorly understood systems. They also engage conflicts between direct human interests and those of other species and the natural world.

Ultimately, the design and implementation of an ecologically sustainable human economy will require a widespread adoption of new world views and cultural attitudes that are based on environmental and ecological ethics, which include consideration for the needs of future generations of people as well as other species and natural ecosystems. This will be the best way of dealing with the so-called “environmental crisis,” a modern phenomenon that is associated with rapid population growth, resource depletion, and environmental damage. This crisis is caused by the combined effects of population increase and an intensification of per-capita environmental damage.

Finally, it must be understood that that the study of environmental issues is not just about the dismal task of understanding awful problems. Rather, a major part of the subject is to find ways to repair many of the damages that have been caused, and to prevent others that might yet occur. These are helpful and hopeful actions, and they represent necessary progress toward an ecologically sustainable economy.

Questions for Review

- Define environmental science, environmental studies, and ecology. List the key disciplinary fields of knowledge that each includes.

- What is the difference between morals and knowledge, and how are these conditioned by personal and societal values?

- Explain how cultural attributes and expressions can affect the ways that people view the natural world and interact with environmental issues.

Questions for Discussion

- Describe how you are connected with ecosystems, both through the resources that you consume (food, energy, and materials) and through your recreational activities. Which of these connections could you do without?

- How are your personal ethical standards related to utilitarian, ecological, aesthetic, and intrinsic values? Think about your world view and discuss how it relates to the anthropocentric, biocentric, and ecocentric world views.

- Make a list of the most important cultural influences that have affected your own attitudes about the natural world and environmental issues.

References Cited and Further Reading

Armstrong, S.J. and R.G. Botzler. 2003. Environmental Ethics: Divergence and Convergence. McGraw-Hill, Columbus, OH.

Botkin, D. 1992. Discordant Harmonies. A New Ecology for the 21st Century. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York.

Brown, L.R. 2003. Plan C: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble. W.W. Norton and Company, New York.

British Petroleum (BP). 2013. Statistical Review of World Energy 2013. BP, London, UK. https://web.archive.org/web/20141023015532/http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2013/ph240/lim1/docs/bpreview.pdf

Callicott, J.B. 1988. In Defense of the Land Ethic: Essays in Environmental Philosophy. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). 2014. The World Factbook. CIA, Langley, VA. https://web.archive.org/web/20140701051751/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2001rank.html

DesJardins, J.R. 2000. Environmental Ethics: An Introduction to Environmental Philosophy. 3rd ed. Wadsworth, Belmont, CA.

Devall, B. and G. Sessions. 1985. Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered. Peregrine Smith Books, Salt Lake City, UT.

Ehrlich, P. and A.H. Ehrlich. 1991. The Population Explosion. Ballantine, New York, NY.

Evernden, L.L.N. 1985. The Natural Alien: Humankind and Environment. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, ON.

Evernden, L.L.N. 1992. The Social Creation of Nature. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

Freedman, B. 1995. Environmental Ecology: The Ecological Effects of Pollution, Disturbance, and Other Stresses. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Hargrove, E.C. 1989. Foundations of Environmental Ethics. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Kuhn, T.S. 1996. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd ed. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Leopold, A. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Livingston, J.A. 1994. Rogue Primate: An Exploration of Human Domestication. Key Porter Books, Toronto, ON.

Miller, G.T. 2006. Living in the Environment. Brooks Cole, Pacific Grove, CA.

Nash, R.F. 1988. The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

Regan, T. 1984. Earthbound: New Introductory Essays in Environmental Ethics. Random House, New York.

Rowe, J.S. 1990. Home Place: Essays on Ecology. NeWest Publishers, Edmonton, AB.

Schumacher, E.F. 1973. Small Is Beautiful. Harper & Row, New York, NY.

Singer, P. 2003. Ethics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Singer, P. 2004. Animal Liberation. Ecco Press, New York, NY.

United States Census Bureau. 2015. International Programs. https://www.census.gov/data-tools/de...ionGateway.php

Wackernagle, M. and E.E. Rees. 1996. Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth. New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, BC.

White, G.F. 1994. Reflections on changing perceptions on the Earth. Annual Review of Energy and Environment, 19: 1–15.

White, L. 1967. The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis. Science 155: 1203–07.

Wilson, E.O. 1984. Biophilia. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.