8.1: Introduction to the Oceans

- Page ID

- 12698

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Have you ever heard the Earth called the “Blue Planet”? This term makes sense, because over 70% of the surface of the Earth is covered with water. The vast majority of that water (97.2%) is in the oceans. Without all that water, our world would be a different place. The oceans are an important part of Earth: they help to determine the make-up of the air, they help determine the weather and temperature, and they support great amounts of life. The composition of ocean water is unique to its location and depth. Just as Earth’s interior is divided into layers, the ocean separated into different layers, called the water column.

Lesson Objectives

- Describe how the oceans formed.

- Explain the significance of the oceans.

- Describe the composition of ocean water.

- Define the parts of the water column and oceanic divisions.

How the Oceans Formed

Scientists have developed a number of hypotheses about how the oceans formed. Though these hypotheses have changed over time, one idea now has the wide support of Earth scientists, called the volcanic outgassing theory. This means that water vapor given off by volcanoes erupting over millions or billions of years, cooled and condensed to form Earth’s oceans.

Creation and Collection of Water

When the Earth was formed 4.6 billion years ago, it would never have been called the Blue Planet. There were no oceans, there was no oxygen in the atmosphere, and no life. But there were violent collisions, explosions, and eruptions. In fact, the Earth in its earliest stage was molten. This allowed elements to separate into layers within the Earth — gravity pulled denser elements toward the Earth’s center, while less dense materials accumulated near the surface. This process of separation created the layers of the Earth as we know them.

As temperatures cooled, the surface solidified and an atmosphere was created. Volcanic eruptions released water vapor from the Earth’s crust, while more water came from asteroids and comets that collided with the Earth (Figure 14.1). About 4 billion years ago, temperatures cooled enough for oceans to begin forming.

Figure 14.1: Volcanic activity was common in Earth’s early stages, when the oceans had not yet begun to form.

Present Ocean Formation

As you know, the continents were not always in the same shape or position as they are today. Because of tectonic plate movements, land masses have moved about the Earth since they were created. About 250 million years ago, all of the continents were arranged in one huge mass of land called Pangea (Figure 14.2). This meant that most of Earth’s water was collected in a huge ocean called Panthalassa. By about 180 million years ago, Pangea had begun to break apart because of continental drift. This then separated the Panthalassa Ocean into separate but connected oceans that are the ocean basins we see today on Earth.

Figure 14.2: Pangea was the sole landform 250 million years ago, leaving a huge ocean called Panthalassa, along with a few smaller oceans.

Significance of the Oceans

The Earth’s oceans play an important role in maintaining the world as we know it. Indeed, the ocean is largely responsible for keeping the temperatures on Earth fairly steady. It may get pretty cold where you live in the wintertime. Some places on Earth get as cold as -70°C. Some places get as hot as 55°C. This is a range of 125°C. But compare that to the surface temperature on Mercury: it ranges from -180°C to 430°C, a range of 610°C. Mercury has neither an atmosphere nor an ocean to buffer temperature changes so it gets both extremely hot and very cold.

Figure 14.3: Coral reefs are amongst the most densely inhabited and diverse areas on the globe.

On Earth, the oceans absorb heat energy from the Sun. Then the ocean currents move the energy from areas of hot water to areas of cold water, and vice versa. Not only does ocean circulation keep the water temperature moderate, but it also affects the temperature of the air. If you examine land temperatures on the Earth, you will notice that the more extreme temperatures occur in the middle of continents, whereas temperatures near the water tend to be more moderate. This is because water retains heat longer than land. Summer temperatures will therefore not be as hot, and winter temperatures won’t be as cold, because the water takes a long time to heat up or cool down. If we didn’t have the oceans, the temperature range would be much greater, and humans could not live in those harsh conditions.

The ocean is home to an enormous amount of life. This includes many kinds of microscopic life, plants and algae, invertebrates like sea stars and jellyfish, fish, reptiles, and marine mammals. The many different creatures of the ocean form a vast and complicated food web, that actually makes up the majority of all biomass on Earth. (Biomass is the total weight of living organisms in a particular area.) We depend on the ocean as a source of food and even the oxygen created by marine plants. Scientists are still discovering new creatures and features of the oceans, as well as learning more about marine ecosystems (Figure 14.3).

Finally, the ocean provides the starting point for the Earth’s water cycle. Most of the water that evaporates into the atmosphere initially comes from the ocean. This water, in turn, falls on land in the form of precipitation. It creates snow and ice, streams and ponds, without which people would have little fresh water. A world without oceans would be a world without you and me.

Composition of Ocean Water

Water has oftentimes been referred to as the “universal solvent”, because many things can dissolve in water (Figure 14.4). Many things like salts, sugars, acids, bases, and other organic molecules can be dissolved in water. Pollution of ocean water is a major problem in some areas because many toxic substances easily mix with water.

Figure 14.4: Ocean water is composed of many substances. The salts include sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, and calcium chloride.

Perhaps the most important substance dissolved in the ocean is salt. Everyone knows that ocean water tastes salty. That salt comes from mineral deposits that find their way to the ocean through the water cycle. Salts comprise about 3.5% of the mass of ocean water. Depending on specific location, the salt content or salinity can vary. Where ocean water mixes with fresh water, like at the mouth of a river, the salinity will be lower. But where there is lots of evaporation and little circulation of water, salinity can be much higher. The Dead Sea, for example, has 30% salinity—nearly nine times the average salinity of ocean water. It is called the Dead Sea because so few organisms can live in its super salty water.

The density (mass per volume) of seawater is greater than that of fresh water because it has so many dissolved substances in it. When water is more dense, it sinks down to the bottom. Surface waters are usually lower in density and less saline. Temperature affects density too. Warm water is less dense and colder waters are more dense. These differences in density create movement of water or deep ocean currents that transport water from the surface to greater depths.

The Water Column

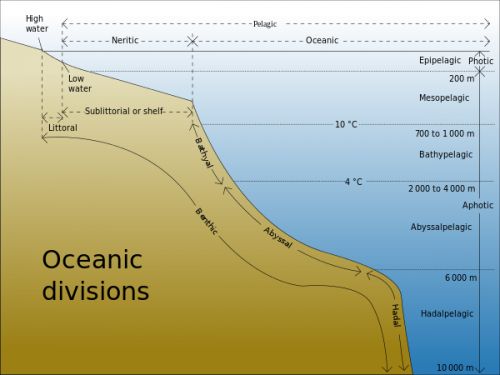

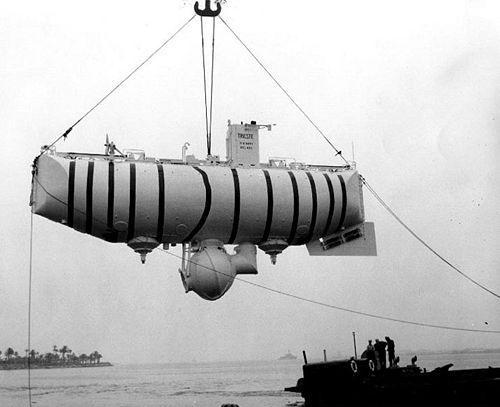

In 1960, one of the deepest parts of the ocean (10,910 meters) was reached by two men in a specially designed submarine called the Trieste (Figure 14.5). This part of the ocean has been named the Challenger Deep. In contrast, the average depth of the ocean is 3,790 meters—still an incredible depth for sea creatures to live at and for humans to travel. What makes it so hard to live at the bottom of the ocean? There are three major factors—the absence of light, low temperature, and extremely high pressure. In order to better understand regions of the ocean, the scientists define different regions by depth (Figure 14.6).

Figure 14.5: The Trieste made a record dive to the Challenger Deep in 1960. James Cameron repeated this feat in 2012.

Figure 14.6: The ocean environment is divided into many regions based on factors like availability of light and nutrients. Organisms adapt to the conditions and resources in the regions in which they live.

Sunlight only penetrates water to a depth of about 200 meters, a region called the photic zone (photic means light). Since organisms that photosynthesize depend on sunlight, they can only live in the top 200 meters of water. Such photosynthetic organisms supply almost all the energy and nutrients to the rest of the marine food web. Animals that live deeper than 200 meters mostly feed on whatever drops down from the photic zone.

Beneath the photic zone is the aphotic zone, where there is not enough light for photosynthesis. The aphotic zone makes up the majority of the ocean but a minority of its life forms. Descending to the ocean floor, the water temperature decreases while pressure increases tremendously. Each region is progressively deeper and colder, with the very deepest areas in ocean trenches.

The ocean can also be divided by horizontal distance from the shore. Nearest to the shore lies the intertidal zone. In this region, you might find waves, changes in tide, and constant motion in the water that exposes the water to large amounts of air. Organisms that live in this zone are adapted to withstand waves and exposure to air in low tides, by having strong attachments and hard shells. The neritic zone includes the intertidal zone and the part of the ocean floor that very gradually slopes downward, the continental shelf. Lots of oceanic plants live in this zone, since some sunlight still penetrates to the bottom of the ocean floor in the neritic zone. Beyond the neritic zone is the oceanic zone, where the sloping sea floor takes a much even steeper dive and sunlight does not reach. Animals such as sharks, fish, and whales can be found in this zone. They feed on materials that sink from upper levels, or consume one another. At hydrothermal vents, areas of extremely hot water with lots of dissolved materials allow rare and unusual producers to thrive.

Lesson Summary

- Our oceans originally formed as a water vapor released by volcanic outgassing cooled and condensed.

- The oceans serve the very important role of helping to moderate Earth’s temperatures.

- The oceans are home to a tremendous diversity of life, and algae which are all photosynthetic organisms.

- The main elements dissolved in seawater are chlorine, sodium, magnesium, sulfate and calcium.

- Usual salinity for the oceans is about 3.5% or 35 parts per thousand.

- Some regions in areas of high evaporation, like the Dead Sea, have exceptionally high salinities.

- The photic zone is the surface layer of the oceans, down to about 200m, where there is enough available light for photosynthesis.

- Below the photic zone, the vast majority of the oceans lies within the aphotic zone, where there is not enough light for photosynthesis.

- On average, the ocean floor is about 3,790m but there are ocean trenches as deep as 10,910m.

- The ocean has many biological zones determined by availability of different abiotic factors.

- Neritic zones are nearshore areas, including the intertidal zone. Oceanic zones are offshore regions of the ocean.

Review Questions

- What was the name of the single continent that separated to form today’s continents?

- From what three sources did water originate on Earth?

- What percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by water?

- How do the oceans help to moderate Earth’s temperatures?

- Over time, the Earth’s oceans have become more and more salty. Why?

- What is the most common substance that is dissolved in ocean water?

- What is density?

Vocabulary

- aphotic zone

- The zone in the water column deeper than 200 m. Sunlight does not reach this region of the ocean.

- biomass

- The total mass of living organisms in a certain region.

- current

- The movement of water in a stream, lake, or ocean.

- density

- Mass per volume. The units for density are usually g⁄cm3 or g⁄mL.

- intertidal zone

- The part of the ocean closest to the shore, between low and high tide.

- neritic zone

- The part of the ocean where the continental shelf gradually slopes outward from the edge of the continent. Some sunlight can penetrate this region of the ocean.

- oceanic zone

- The open ocean, where the seafloor is deep. No sunlight reaches the floor of the ocean here.

- Pangea

- The supercontinent that tectonically broke apart about 200 million years ago, forming the continents and oceans that we see today on Earth.

- photic zone

- The topmost region of the water column, extending from the surface down to about 200 m in depth. Sunlight easily penetrates this region of the water column.

- salinity

- A measure of the amount of dissolved salt in water.

- water column

- A vertical column of ocean water, which is divided into different zones according to their depth.

- Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/High_School_Earth_Science/Introduction_to_the_Oceans. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike