6.2: Streams and Rivers

- Page ID

- 12693

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Fresh water in streams, ponds, and lakes is an extremely important part of the water cycle if only because of its importance to living creatures. Along with wetlands, these fresh water regions contain a tremendous variety of organisms.

Streams are bodies of water that have a current; they are in constant motion. Geologists recognize many categories of streams depending on their size, depth, speed, and location. Creeks, brooks, tributaries, bayous, and rivers might all be lumped together as streams. In streams, water always flows downhill, but the form that downhill movement takes varies with rock type, topography, and many other factors. Stream erosion and deposition are extremely important creators and destroyers of landforms and are described in the Erosion and Deposition chapter.

RIVERS

Rivers are the largest types of stream, moving large amounts of water from higher to lower elevations. The Amazon River, the world’s river with the greatest flow, has a flow rate of nearly 220,000 cubic meters per second! People have used rivers since the beginning of civilization as a source of water, food, transportation, defense, power, recreation, and waste disposal.

Rivers and streams complete the hydrologic cycle by returning precipitation that falls on land to the oceans (Figure 10.1). Ultimately, gravity is the driving force, as water moves from mountainous regions to sea level. Some of this water moves over the surface and some moves through the ground as groundwater . As this water flows it does the work of both erosion and deposition. You will learn about the erosional effects and the deposits that form as a result of this moving water.

Lesson Objectives

- Describe how surface rivers and streams produce erosion.

- Describe the types of deposits left behind by rivers and streams.

PARTS OF A STREAM/RIVER

Oddly enough, there are a variety of different types streams. A stream originates at its source. The source is likely to be in the high mountains where snows collect in winter and melt in summer, or a source might be a spring. The source is known as the headwaters or the head of the stream. A stream may have more than one sources and when two streams come together it’s called a confluence. The smaller of the two streams is a tributary of the larger stream. A stream may create a pool where water slows and becomes deeper.The point at which a stream comes into a large body of water, like an ocean or a lake is called the mouth.

A divide is a topographically high area that separates a landscape into different water basins. Rain that falls on the north side of a ridge flows into the northern drainage basin and rain that falls on the south side flows into the southern drainage basin. On a much grander scale, entire continents have divides, known as continental divides.

Erosion and Deposition by Rivers and Streams

Erosion from Runoff

As streams move over the ground, they transport weathered materials. Streams continually erode material away from their banks, especially along the outside curves of meanders. Some of these materials are carried in solution. Many minerals are ionic compounds that dissolve easily in water, so water moves these elements to the sea as part of the dissolved load that the stream carries. As groundwater leaches through layers of soil and rock, minerals dissolve and are carried away. Groundwater contributes most of the dissolved components that streams carry. Once an element has completely dissolved, it will likely be carried to the ocean, regardless of the velocity of the stream. In some circumstances, the stream water could become saturated with dissolved materials, in which case elements of those minerals might precipitate out of the water before they reach the ocean.

Another way that rivers and streams move weathered materials is as the suspended load. These are pieces of rock that are carried as solids as the river flows. Unlike dissolved load, the size of the particle that can be carried as suspended load is determined by the velocity of the stream. As a stream flows faster, it can carry larger and larger particles. The larger the size particle that can be carried by a stream, the greater the stream’s competence. If a stream has a steep slope or gradient, it will have a faster velocity, which means it will be able to carry larger materials in suspension. At flood stage, rivers flow much faster and do more erosion because the added water increases the stream’s velocity. Sand, silt and clay size particles generally make up the suspended load for a stream (Figure 10.2). As a stream slows down, either because the stream’s slope decreases or because the stream overflows its banks and broadens its channel, the stream will deposit the largest particles it has been carrying first.

The last way that rivers and streams move weathered materials is as bed load. This means that although the water in the stream is capable of bumping and pushing these particles along, it is not able to pick them up and carry them continuously. Bed load is named for the fact that these particles get nudged and rolled along the stream bed as the water flows. Occasionally a larger size particle will get knocked into the main part of the stream flow, but then it settles back down to the stream bed because it is too heavy to remain suspended in the water. This is called saltation, which we will learn about later in this chapter with transport of particles by wind. Streams with high velocities and steep gradients do a great deal of downcutting into the stream bed, which is primarily accomplished by movement of particles that make up the bed load. Particles that move along as the bed load of a stream do not move continuously along, but rather in small steps or jumps with periods of remaining stationary in between.

Stream and River Erosion

As a stream moves water from high elevations, like mountains, towards low elevations, like the ocean, which is at sea level, the work of the stream changes. At high elevations, streams are just beginning streams that have small channels and steep gradients. This means that the stream will have a high velocity and will do lots of work eroding its stream bed. The higher the elevation, the farther the stream is from where it eventually meets the sea. Base level is the term for where a stream meets sea level or standing water, like a lake or the ocean. Streams will work to downcut their stream beds until they reach base level.

As a stream moves out of high mountainous areas into lower areas closer to sea level, the stream is closer to its base level and does more work eroding the edges of its banks than downcutting into its stream bed. At some point in most streams, there are curves or bends in the stream channel called meanders (Figure 10.3). The stream erodes material along its outer banks and deposits material along the inside curves of a meander as it flows to the ocean (Figure 10.4). This causes these meanders to migrate laterally over time. The erosion of the outside edge of the stream’s banks begins the work of carving a floodplain, which is a flat level area surrounding the stream channel.

Stream and River Deposition

Once a stream nears the ocean, it is very close to its base level and now deposits more materials than it erodes. As you just learned, one place where a river deposits material is along the inside edges of meanders. If you ever decide to pan for gold or look for artifacts from an older town or civilization, you will sift through these deposits. Gold is one of the densest elements on Earth. Streams are lazy and never want to carry more materials than absolutely necessary. It will drop off the heaviest and largest particles first, that is why you might find gold in a stream deposit. Imagine that you had to carry all that you would need for a week as you walked many kilometers. At first you might not mind the weight of what you are carrying at all, but as you get tired, you will look to drop off the heaviest things you are carrying first!

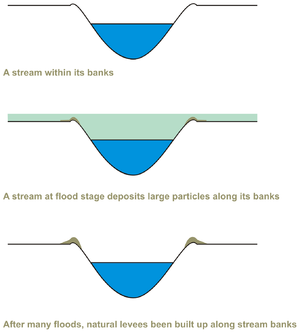

When a river floods or overflows its channel, the area where the stream flows is suddenly much broader and shallower than it was when it was in its channel. This slows down the velocity of the stream’s flow and causes the stream to drop off much of its load. The farmers who use the floodplain areas around the Nile River rely on these deposits to supply nutrients to their fields each year as the river floods its banks. At flood stage, a river will also build natural levees as the largest size particles build a higher area around the edges of the stream channel (Figure 10.5).

When a river meets either standing water or nearly flat lying ground, it will deposit its load. If this happens in water, a river may form a delta. From its headwaters in the mountains, along a journey of many kilometers, rivers carry the eroded materials that form their stream load. Suddenly the river slows down tremendously in velocity, and drops the tremendous load of sediments it has been carrying. Deltas are relatively flat topped, often triangular shaped deposits of sediments that form where a large river meets the ocean. The name delta comes from the capital Greek letter delta, which is a triangle, even though not all deltas have this shape. A triangular shaped delta forms as the main stream channel splits into many smaller distributaries. As the channel shifts back and forth dropping off sediments and moving to a new channel location a wide triangular deposit forms.

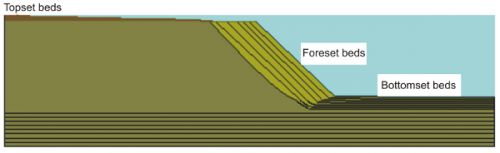

There are three types of beds that make up a delta (Figure 10.6). The first particles to be dropped off are the coarsest sediments and these form sloped layers called foreset beds that make up the front edge of the delta. Further out into calmer water, lighter, more fine grained sediments form thin, horizontal layers. These are called bottomset beds. During floodstage, the whole delta can be covered by finer sediments which will overlie the existing delta. These are called topset beds. These form last and lie on top of the rest of the delta.

Not all large rivers form deltas as they meet the ocean. Whether a delta forms depends on the action of waves and tides. If the water is quiet water such as a gulf or shallow sea, a delta may form. If the sediments are carried away, then no delta will form. Sediments brought to the shore and distributed along coastlines by longshore transport form our beaches and barrier islands.

If a river or stream suddenly reaches nearly flat ground, like a broad flat valley or plain, an alluvial fan develops at the base of the slope (Figure 10.7). An alluvial fan is a curved top, fan shaped deposit of coarse sediments that drop off as the stream suddenly loses velocity. The fan spreads out in a curve in the direction of the flat land as many stream channels move across the curved surface of the alluvial fan, forming and unforming many channels as sediments are deposited. Alluvial fans generally form in more arid regions.

Lesson Summary

- Rivers and streams erode the land as they move from higher elevations to the sea.

- Eroded materials can be carried in a river as dissolved load, suspended load, or bed load.

- A river will deeply erode the land when it is far from its base level, the elevation where it enters standing water like the ocean.

- As a river develops bends, called meanders, it forms a broad, flat area known as a floodplain.

- At the end of a stream, a delta or an alluvial fan might form where the river drops off much of the load of sediments it carries.

Review Questions

- What are the three kinds of load that make up the particles a stream carries. Name and define each type.

- What is a stream’s gradient? What effect does it have on the work of a stream?

- Describe several erosional areas produced by streams. Explain why erosion occurs here.

- What type of gradient or slope would a river have when it is actively eroding its stream bed? Explain.

- When would a river form an alluvial fan and when will it form a delta? Describe the characteristics of each type of deposit.

- Earth Science for High School. Provided by: CK-12. Located at: http://www.ck12.org/book/CK-12-Earth-Science-For-High-School/?noindex=None. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial