16.3: The Sun

- Page ID

- 12723

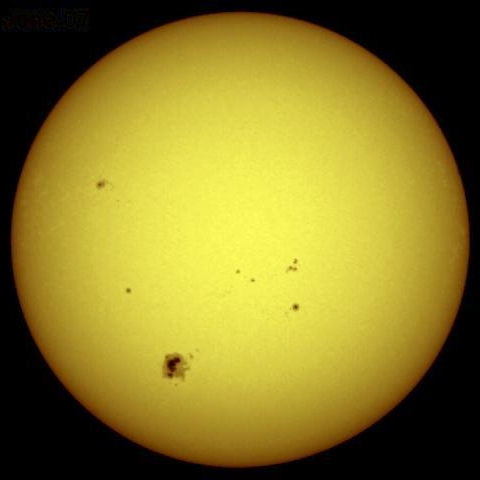

Consider the Earth, the Moon, and all the other planets in our solar system. Think about the mass that all those objects must have when they are all added together. Added all together, however, they account for only 0.2% of the total mass of the solar system. The Sun makes up the remaining 99.8% of all the mass in the solar system (Figure 24.17)! The Sun is the center of the solar system and the largest object in the solar system. Our Sun is a star that provides light and heat and supports almost all life on Earth.

In this lesson you will learn about the features of the Sun. We will discuss the composition of the Sun, its atmosphere, and some of its surface features.

Figure 24.17: The Sun.

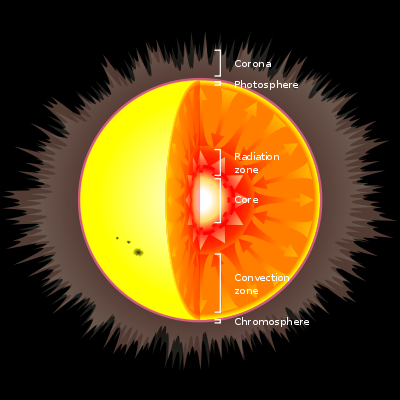

Layers of the Sun

The Sun is a sphere, but unlike the Earth and the Moon, is not solid. Most atoms in the Sun exist as plasma, or a fourth state of matter made up of superheated gas with an electrical charge. Our Sun consists almost entirely of the elements hydrogen and helium. Because the Sun is not solid, it does not have a defined outer boundary. It does, however, have a definite internal structure. There are several identifiable layers of the Sun:

The core is the innermost or central layer of the Sun. The core is plasma, but moves similarly to a gas. Its temperature is around 27 million degrees Celsius. In the core, nuclear reactions combine hydrogen atoms to form helium, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process. The energy released then begins to move outward, towards the outer layers of the Sun.

The radiative zone is just outside the core, which has a temperature of about 7 million degrees Celsius. The energy released in the core travels extremely slowly through the radiative zone. Particles of light called photons can only travel a few millimeters before they hit another particle in the Sun, are absorbed and then released again. It can take a photon as long as 50 million years to travel all the way through the radiative zone.

The convection zone surrounds the radiative zone. In the convection zone, hot material from near the Sun’s center rises, cools at the surface, and then plunges back downward to receive more heat from the radiative zone. This movement helps to create solar flares and sunspots, which we’ll learn more about in a bit. These first three layers make up what we would actually call “the Sun”. The next three layers make up the Sun’s atmosphere. Of course, there are no solid layers to any part of the Sun, so these boundaries are fuzzy and indistinct.

The Sun’s “Atmosphere”

The photosphere is the visible surface of the Sun (Figure 24.18). This is the region of the Sun that emits sunlight. It’s also one of the coolest layers of the Sun—only about 6700°C. Looking at a photograph of the Sun’s surface, you can see that it has several different colors; oranges, yellow and reds, giving it a grainy appearance. We cannot see this when we glance quickly at the Sun. Our eyes can’t focus that quickly and the Sun is too bright for us to look at for more than a brief moment. Looking at the Sun for any length of time can cause blindness, so don’t try it! Sunlight is emitted from the Sun’s photosphere. A fraction of the light that travels from the Sun reaches Earth. It travels as light in a range of wavelengths, including visible light, ultraviolet, and infrared radiation. Visible light is all the light we can see with our eyes. We can’t see ultraviolet and infrared radiation, but their effects can still be detected. For example, a sunburn is caused by ultraviolet radiation when you spend too much time in the Sun.

Figure 24.18: The layers of the Sun.

The chromosphere is the zone about 2,000 kilometers thick that lies directly above the photosphere. The chromosphere is a thin region of the Sun’s atmosphere that glows red as it is heated by energy from the photosphere. Temperatures in the chromosphere range from about 4000°C to about 10,000°C. Jets of gas fire up through the chromosphere at speeds up to 72,000 kilometers per hour, reaching heights as high as 10,000 kilometers.

The corona is the outermost layer of the Sun and is the outermost part of its atmosphere. It is the Sun’s halo or “crown”. It has a temperature of 2 to 5 million degrees Celsius and is much hotter than the visible surface of the Sun, or photosphere. The corona extends millions of kilometers into space. If you ever have the chance to see a total solar eclipse, you will be able to see the Sun’s corona, shining out into space.

In the Sun’s core, nuclear fusion reactions generate energy by converting hydrogen to helium. Fusion is a process where the nuclei of atoms join together to form a heavier chemical element. Fusion reactions in the Sun’s core produce energy, which we experience as heat and light. The rest of the Sun is heated by movement of heat energy outward from the core. Light energy from the Sun is emitted from the photosphere. It travels through space, and some of it reaches the Earth. The Sun is the source of almost all the energy on Earth and sunlight powers photosynthesis, as well as warming and illuminating our Earth.

Surface Features of the Sun

The most noticeable surface feature of the Sun is the presence of sunspots, which are cooler, darker areas on the Sun’s surface. Sunspots are only visible with special light-filtering lenses. They exhibit intense magnetic activity. These areas are cooler and darker because loops of the Sun’s magnetic field break through the surface and disrupt the smooth transfer of heat from lower layers. Sunspots usually occur in pairs. When a loop of the Sun’s magnetic field breaks through the surface, it usually creates a sunspot both where it comes out and one where it goes back in again. Sunspots usually occur in 11 year cycles, beginning when the number of sunspots is at a minimum, increasing to a maximum number of sunspots and then gradually decreasing to a minimum number of sunspots again.

If a loop of the sun’s magnetic field snaps and breaks, it creates solar flares, which are violent explosions that release huge amounts of energy (Figure 24.19). They release streams of highly energetic particles that make up the solar wind. The solar wind can be dangerous to spacecraft and astronauts. It sends out large amounts of radiation, which can harm the human body. Solar flares have knocked out entire power grids and can disturb radio, satellite, and cell phone communications.

Figure 24.19: A solar flare.

Another highly visible feature on the Sun are solar prominences. If plasma flows along a loop of the Sun’s magnetic field from sunspot to sunspot, it forms a glowing arch that reaches thousands of kilometers into the Sun’s atmosphere. Prominences can last for a day to several months. Prominences are also visible during a total solar eclipse.

A beautiful and mysterious effect of the Sun’s electrically charged particles are auroras, which form around the polar regions high in Earth’s atmosphere. Gases in Earth’s atmosphere are excited by the electrically charged particles of the solar wind and glow producing curtains of light, which bend and change as you watch.

Lesson Summary

- The mass of the Sun is tremendous. It makes up 99.8% of the mass of our solar system.

- The Sun is mostly made of hydrogen with smaller amounts of helium in the form of plasma.

- The main part of the Sun has three layers: the core, the radiative zone, and the convection zone.

- The Sun’s atmosphere also has three layers: the photosphere, the chromosphere, and the corona.

- Nuclear fusion of hydrogen in the core of the Sun produces tremendous amounts of energy that radiate out from the Sun.

- Some features of the Sun’s surface include sunspots, solar flares, and prominences.

Review Questions

- In what way does the Sun support all life on Earth?

- Which two elements make up the Sun almost in entirety?

- Which process is the source of heat in the Sun and where does it take place?

- Some scientists would like to plan a trip to take humans to Mars. One of the things standing in the way of our ability to do this is solar wind. Why will we have to be concerned with solar wind?

- Describe how movements in the convection zone contribute to solar flares.

- Do you think fusion reactions in the Sun’s core will continue forever and go on with no end? Explain your answer.

Vocabulary

- chromosphere

- Thin layer of the Sun’s atmosphere that lies directly above the photosphere; glows red.

- convection zone

- Layer of the Sun that surrounds the Radiative Zone; energy moves as flowing cells of gas.

- core

- Innermost or central layer of the Sun.

- corona

- Outermost layer of the Sun; a plasma that extends millions of kilometers into space.

- nuclear fusion

- The merging together of the nuclei of atoms to form new, heavier chemical elements; huge amounts of nuclear energy are released in the process.

- photosphere

- Layer of the Sun that we see; the visible surface of the Sun.

- photosynthesis

- The process that green plants use to convert sunlight to energy.

- plasma

- A high energy, high temperature form of matter. Electrons are removed from atoms, leaving each atom with an electrical charge.

- radiation

- Electromagnetic energy; photons.

- radiative zone

- Layer of the Sun immediately surrounding the core; energy moves atom to atom as electromagnetic waves.

- solar flare

- A violent explosion on the Sun’s surface.

- solar wind

- A stream of radiation emitted by a solar flare. The solar wind extends millions of kilometers out into space and can even reach the Earth.

- sunspots

- Cooler, darker areas on the Sun’s surface that have lower temperatures than surrounding areas; sunspots usually occur in pairs.

Points to Consider

- If something were to suddenly cause nuclear fusion to stop in the Sun, how would we know?

- Are there any types of dangerous energy from the Sun? What might be affected by them?

- If the Sun is all made of gases like hydrogen and helium, how can it have layers?

- Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/High_School_Earth_Science/The_Sun. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike